Physiology News Magazine

Thinking a little differently

A member reflects on life as a neurodivergent physiologist

Membership

Thinking a little differently

A member reflects on life as a neurodivergent physiologist

Membership

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.123.44

Michael B Vaughan, University College Cork, Ireland

I believe most neurodiverse people always have some inkling that they are different. It’s not until your differences start to inconvenience the outside world that a diagnosis is sought. For many, that means assessment as a child, but for others it can be much later in life. I learned that I was dyslexic when I was 18 after the umpteenth argument with my teachers over my spelling and handwriting. Recently, at the age of 25 I have learnt that I also have ADHD. It turns out PhDs require some amount of executive function, self-motivation, and the ability to sit down and do tedious things for extended periods of time. My self-devised compensations could no longer bridge the gap.

Since I still find it rather difficult to explain neurodiversity, I will use someone else’s words. “Neurodiversity is the idea that neurological differences like autism and adhd are the result of normal, natural variation in the human genome. This represents new and fundamentally different way of looking at conditions that were traditionally pathologized” John Elder Robison

While not denying the medical significance of disabilities arising from neurodevelopmental conditions, neurodiversity addresses how an individual’s sense of self and how they understand the world around them can be different based on their brain. This difference, unlike neurological conditions, is not something that needs to be cured.

For example, there is compelling evidence showing the previous genetic advantage of ADHD to ancient people, and the slow selection against it since the advent of farming (Esteller-Cucala et al., 2020). A 2008 study found that nomadic Kenyan tribesmen bearing dopamine receptor mutations associated with ADHD were better nourished than those without it (Eisenberg et al., 2008). The opposite was true for their settled neighbours. Those with ADHD don’t then have an illness, but have traits better suited to hunting and gathering rather than spreadsheet maintenance.

So how has being neurodivergent shaped my experience of research life?

On the plus, when you have an insatiable need to learn and a constant craving for new stimuli, a university is the best place to be. From my home in the physiology department, I have wandered into virology, pharmacology, biochemistry, applied psychology, computer science, ancient Roman history, poetry, languages, illustration, innovation, consultancy, opened a company, closed a company, joined an unnecessary number of university committees and started a rebellious student group or two. My competencies within each of these disciplines is as varied as the disciplines themselves; I wouldn’t hire myself as a portrait artist nor to build a website, but I had a great time exploring.

As a scientist, my project proposals, so I have been told, are almost always creative and novel. I have been told I bring a chaotic energy to any project I join that always inspires change. The unfortunate counterpoint to this is that trying to get me to write up that project proposal as a grant application is not going to go well. Sitting down to write a review for several days is my definition of torture. If a task I am asked to do cannot be carried out immediately, I’ll likely forget to do it. The day-to-day of research life doesn’t suit me, but I am still here, thanks to the kindness and patience of those around me.

When I recognised that I was having chronic issues that were resistant to most of my efforts, I asked for help. I talked to my supervisory team, and we restructured how my work was planned, executed and supervised. I will forget to do things or procrastinate if I don’t have deadlines, so we started to meet more regularly to keep me accountable. Not knowing the next step in terms of producing a thesis caused me a lot of stress, so we broke down all tasks into smaller chunks. “We will see what happens” is an approach that is only allowed for side projects, not the next main step in my thesis.

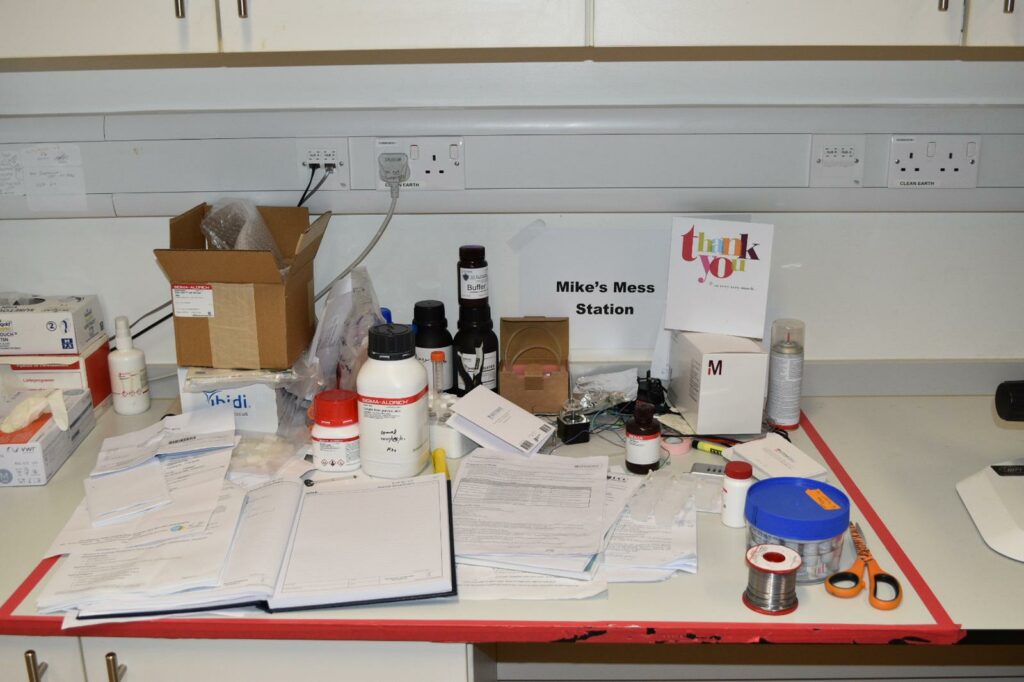

My favourite of the accommodations1 made for me actually happened prior to any diagnosis. As the only person in the lab over the first lockdown, I started to spread my equipment out across the lab. When my lab partner came back and started putting things away, I would forget to do certain tasks and we argued frequently over where things were and where they should be. Our solution was to mark out an area. Anything I am working on needs to stay in that area, and anything anyone else finds where it shouldn’t be, it gets put there. The area is a mess, but the disputes have stopped, and I can always see what needs to be done. We are lucky that we have the space to designate a whole bench top to my mess, but there are many other instances when neurodivergent accommodations are easier to incorporate than this. First and foremost, be a patient communicator. While neurodiversity is varied, difficulty in healthy communication is a frequent problem.

The best advice I can provide for someone trying to understand neurodiverse people is to consider them someone whose native language is different to yours; while we may speak your language very well, odds are that our definition of certain words and turns of phrase are different. Our approach to a problem, task or social interaction might be more influenced by our neurodiversity than what is acceptable in the culture we grew up in. The same way us Irish people have to forgive foreigners for answering the question “How’re you getting on?” with any response other than “Grand” or “Tipping away”, you may need to forgive your neurodiverse friends for sounding a little too curt.

The way I communicate is often misconstrued as indifference, condescension, or arrogance, when I may just have shortened a long sentence in my head in a way that I assume makes sense to everyone else. While I am responsible for making the extra effort to try not to upset others, the kindest accommodation those close to me provide is asking “What do you mean?”. If I say something that may sound problematic, they pause, take a breath, and ask. Most of the time, the comment really didn’t mean anything. Occasionally of course, I actually am being rude, and then they can call me on it.

I am hoping anyone that reads this will consider looking into accommodations they can provide within their labs or in other walks of life. It’s not only the neurodiverse that benefit from an extra bit of patience, or a bit more tailoring of tasks and workflows. We would all feel better being given the benefit of the doubt. Diversity will keep things interesting, and a bit of kindness keeps things going.

References and Resources

1. Accommodations refer to any change made to make an environment or situation more suitable to a neurodiverse individual. They can be made in workplaces, homes, public spaces and relationships. Accommodations do not remove agency or accountability from the individual, but ensure no unnecessary extra burden is placed upon them.

2. Robison, JE (2013). What Is Neurodiversity? Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/my-life-aspergers/201310/what-is-neurodiversity