Physiology News Magazine

Transdisciplinary science and art

How drawing and notebook creation improved student accessibility to complex scientific concepts

Features

Transdisciplinary science and art

How drawing and notebook creation improved student accessibility to complex scientific concepts

Features

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.130.21

Dr Francesca Arrigoni

Kingston University, UK

“Hands up, who hates drawing?” seems a reasonable question to ask pharmacy students just before embarking on a transdisciplinary Science and Art lesson. Unsure of what trauma science students must have experienced in their previous education for a few to raise their hands, I remain hopeful, as it’s never quite as bad as the visceral reactions from some art lecturers when asked, “Who enjoys maths?”

As an educator I don’t think that these disciplines are mutually exclusive. Whilst science makes sense of the world and converts the things that we see around us into knowledge, art takes our perceptions and questions them. There is an iterative process at work, where without our perceptions and the questioning of our perceptions, science would not have such a rich foundation to build upon. Science is a creative process. It is known that most science Nobel Prize winners practice art in some form (Root-Bernstein and Root- Bernstein, 2023).

The cost of moving from analogue to digital learning

As we increasingly move into a digital age and AI, as hard copies of textbooks move into an online format, those analogue skills in university courses such as note taking and drawing become sidelined and students lose essential practical skills.

For pharmacy students to engage with the lists of information they must learn and to make the learning process less passive and didactic, we deliver flipped lectures, workshops, and tutorials to enable students to be present in the moment and enjoy the subject. However, a triumvirate of circumstances that include teaching a core subject such as physiology integrated into another course, the attainment gap and information-rich syllabuses means even these approaches to teaching may not be as effective in engaging students (Lujan and DiCarlo, 2006).

While it is recognised that students have come to university to appreciate our expertise and to be immersed in university life, for many the realities are that they will be commuting, they may have jobs and they may have dependents and/or small children. They will bring different skills and experiences to the table, but this may come at a cost of engagement and deeper learning.

STEAM

Students who will work competitively in a global market need to acquire those deeper learning skills to enable them to succeed and thrive, some of which have been deconstructed into critical and creative thinking. A delightful acronym of STEAM, Science, Technology, Engineering, Art and Maths, is gaining traction and many find their teaching increasingly utilising it to address those skills (Perales and Aróstegui, 2021).

In the Department of Pharmacy at Kingston University, an online drawing class was created to supplement a dissection practical during the pandemic, which could enable students to spend time closely observing the heart. This fine art approach to cardiac physiology led to improved essay results for those students who engaged (Arrigoni, 2021). Over time, as popularity grew and nursing and midwifery courses across the faculty took up the online course, the content expanded to include instruction for drawing gross and detailed kidney anatomy with videos created to support those students who were on placements.

In 2022, art-physiology was finally taught face to face, embedded into a now award-winning nursing elective. Having successfully taught nursing students complex cardiac physiology and visual thinking using art (Blackie et al., 2023), it was clear that the process of drawing had enabled students to voluntarily work outside the hours of the class, helping them learn independently.

The next step was to equip students with a skill set to induce curiosity, scientifically observe, and voluntarily question.

The Pharmacognosy of Poisons

Collaborations with Kingston School of Art increased the ability to work in an outward facing fashion, and an exciting title of a short pilot course was created, “The Pharmacognosy of Poisons”, based on the Economic Botany Collection at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. To recruit students, posters were put up before lectures in which students were told about the course, that botanical art was involved and that there would be a field trip to the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Eight students signed up.

The Economic Botany Collection

The Economic Botany Collection at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew is an extraordinary range of artefacts, all derived from specimens collected through global partnerships. These artefacts all contain a narrative with a particular emphasis on regions affected by British colonialism or trade.

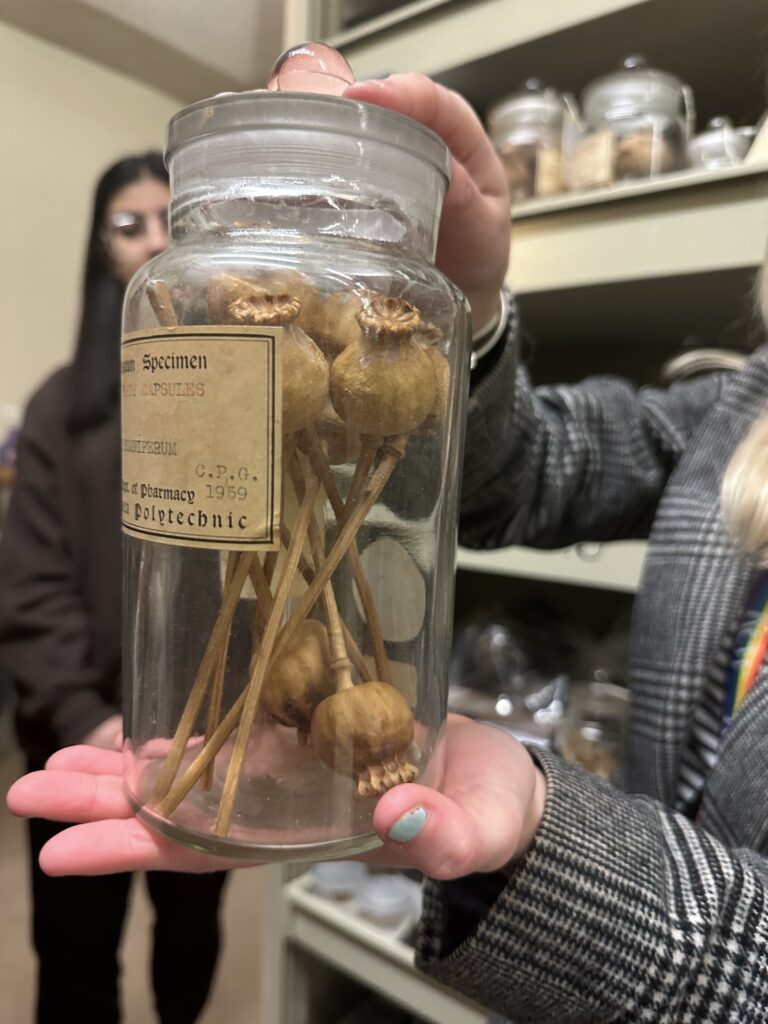

Plants were chosen that were both available from the Economic Botany Collection and that would align with the student curriculum, Abrus Precatorius/(Rosary pea) seeds, Chondrodendron tomentosum/Curare d-tubocurarine, Illicium verum/Star Anise, and Papaver somniferum/Opium (Fig.1).

Nature journalling

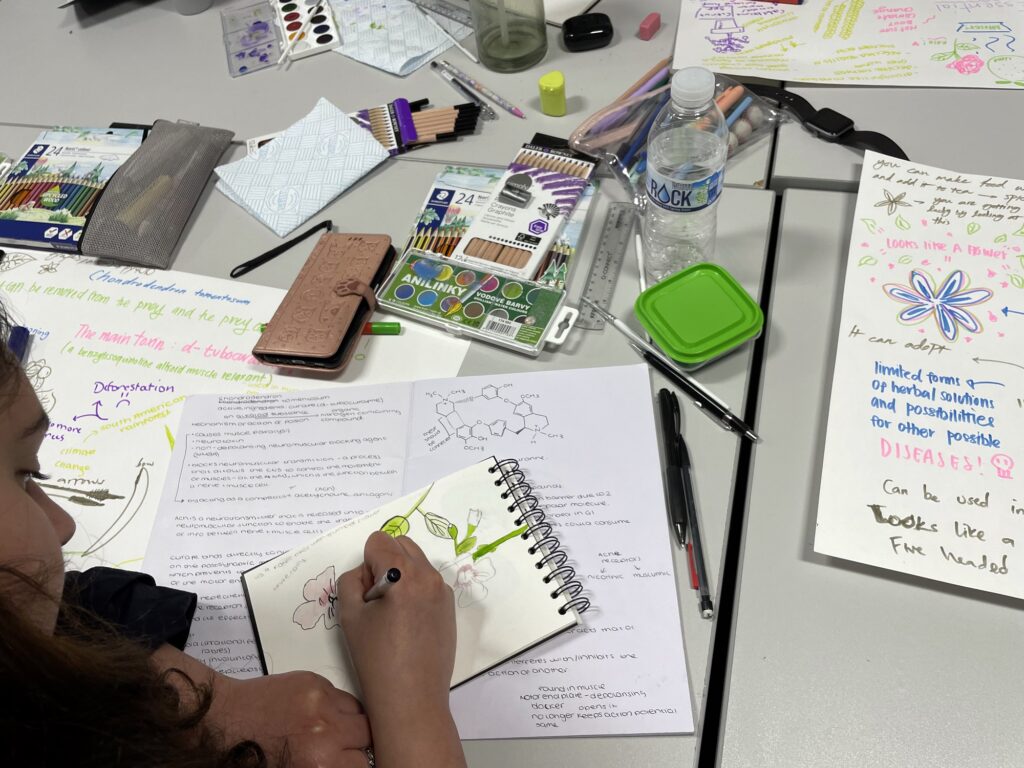

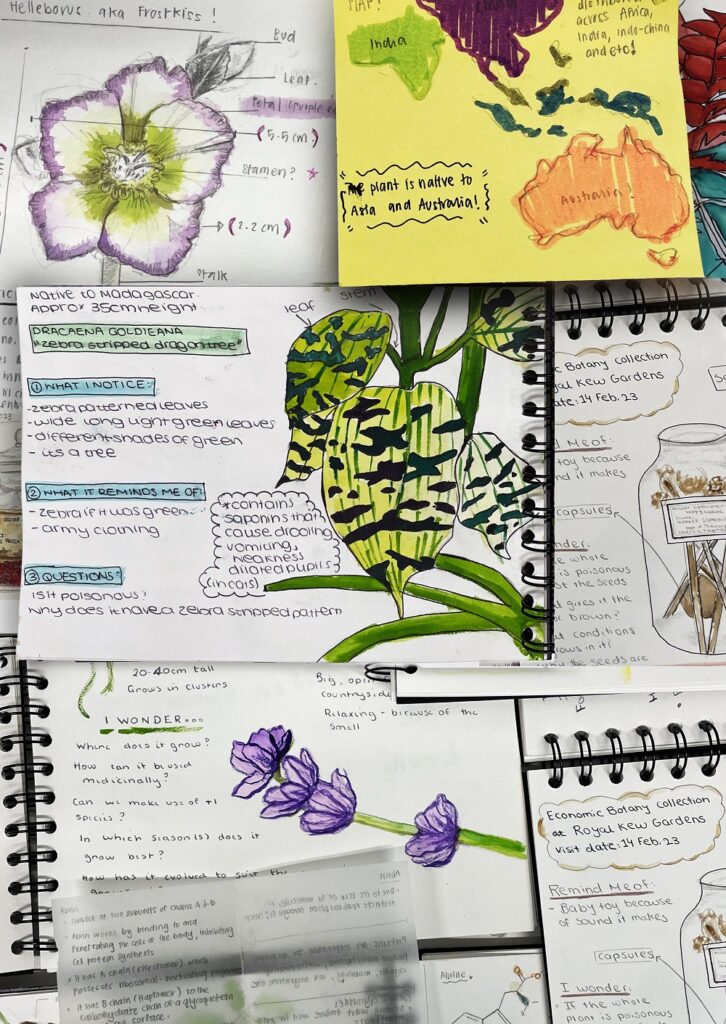

Students were provided with drawing equipment, taught botanical art, how to draw accurately, draughtmanship of their images and the lifecycles of the plants alongside elementary botany and plant structure/function. They then learnt how to create a nature journalling notebook, promoting a creative approach to critical thinking. It was composed of three steps: close observation, questioning the observation and asking yourself “why?” It creates links between observations and thoughts (Laws 2020) (Fig.2).

Embedding transdisciplinary content into a course can improve both student and teaching experiences

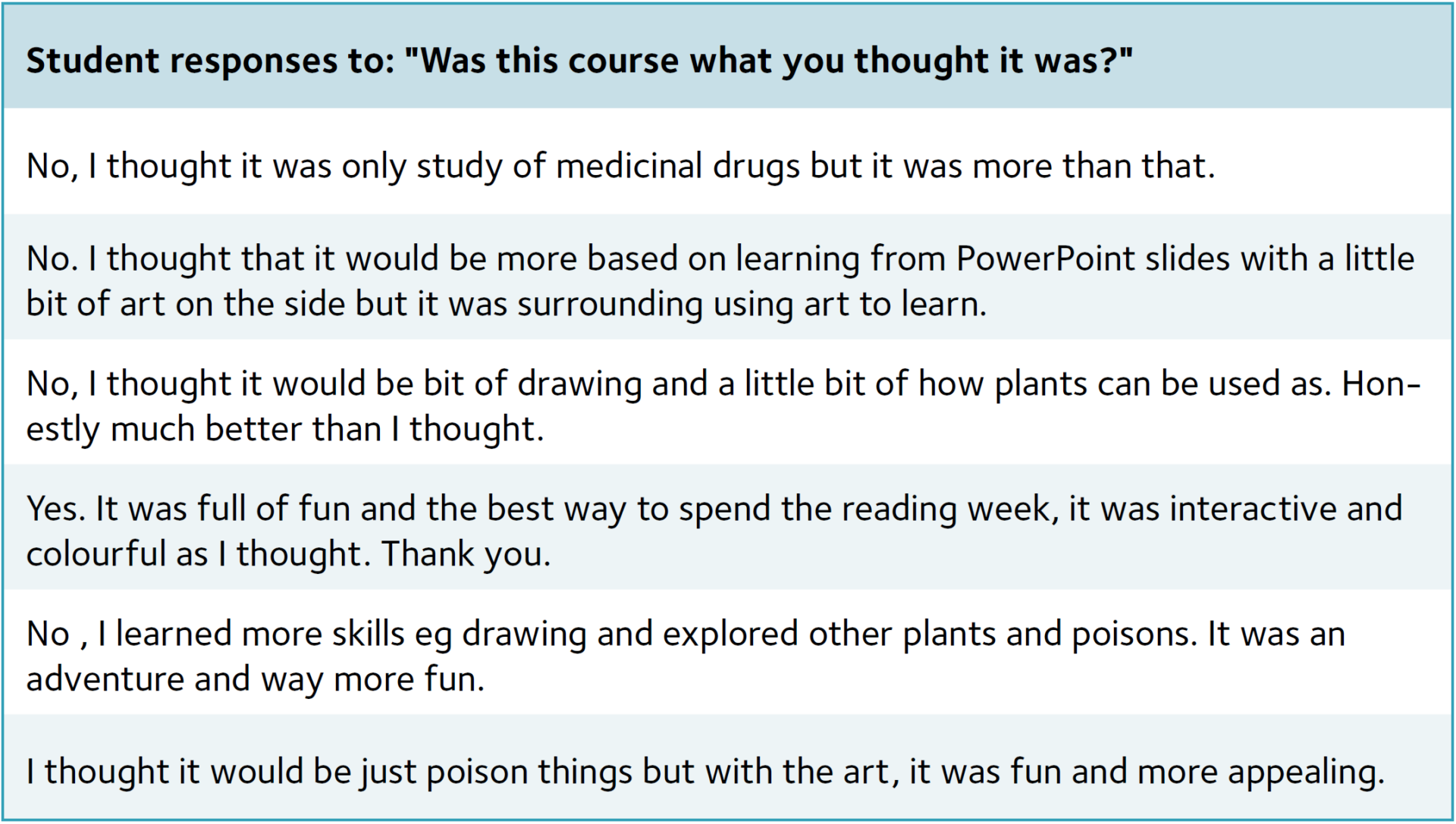

Positive results from test scores and the feedback from the questionnaires (Table 1), demonstrated the positive impact on both knowledge uptake and accessibility to the subjects while the notebooks the students had created were an easy way to assess their engagement and understanding.

Feedback from all students was overwhelmingly positive. This provided evidence that it was possible to embed transdisciplinary content into a course and improve both student and teaching experiences, during which students could acquire creative and critical thinking skills and a deeper understanding of the subject they were studying (Balemans et al., 2016).

Interestingly, as the week progressed the students’ confidence grew in the tasks that they were undertaking, and they became more motivated. With this new-found motivation, they had agency to make decisions of how they wanted to progress with their studies of the plants and their pharmacology, reflected in their work and feedback (Fig.3). Recreating this level of positive feedback in a laboratory setting may take days or even weeks, at great expense.

The next steps

Artwork is very accessible as a discipline and can be a means of improved physical observation, increased tolerance for ambiguity, and increased interest in communication skills (Klugman and Beckmann-Mendez, 2015). This study and others have increasingly demonstrated the positive impact that such a simple technique can have in lowering barriers to science education and learning to anyone. Preconceptions and negative expectations appear to be the biggest obstructions to students and staff engaging with art as a learning and teaching tool. The next steps will be removing these barriers by increasing the visibility of transdisciplinary science and art successes.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Clare Conway, Kingston School of Art for collating the student images and Erin Messenger, from the Economic Botany Collection, Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew.

References

Arrigoni FIF (2021). Transdisciplinary teaching in physiology to improve creative thinking. Paper

presented: BERA (British Educational Research Association) Annual Conference; 13 – 16 Sep [online]. Available at: https://eprints.kingston.ac.uk/id/eprint/50094/

Balemans MC et al. (2016). Actual drawing of histological images improves knowledge retention. Anatomical Sciences Education 9 (1):60-70. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.1545

Blackie C et al. (2023). Teaching Innovation of the Year 2023 (simulated public health elective), Student Nursing Times 2023.

Klugman CM, Beckmann-Mendez D (2015). One thousand words: evaluating an interdisciplinary art education program. Journal of Nursing Education 54(4), 220-22. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20150318-06

Laws JM (2020). How to Teach Nature Journaling: A Science and Art Manual for Parents, Educators, and Naturalists. Heyday.

Lujan HL, DiCarlo SE (2006). Too much teaching, not enough learning: what is the solution? Advances in Physiology Education 30(1) 17-22. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00061.2005

Root-Bernstein M, Root-Bernstein R (2023). Polymathy among nobel laureates as a creative strategy— the qualitative and phenomenological evidence. Creativity Research Journal 35(1), 116-142. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2022.2051294

Perales FJ, Aróstegui JL (2021). The STEAM approach: Implementation and educational, social and economic consequences. Arts Education Policy Review 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632913.2021.1974997