By Mark Burnley, University of Kent, UK.

By Mark Burnley, University of Kent, UK.

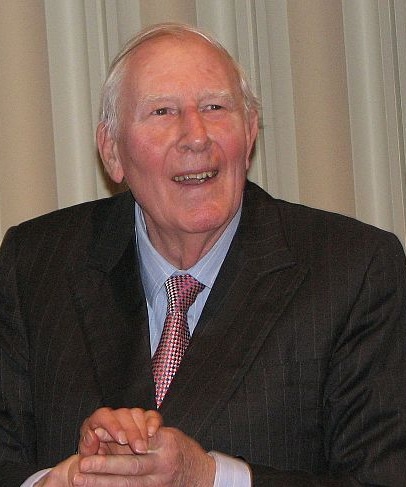

On Saturday March 3, 2018, Sir Roger Bannister, the first person to run a mile in under 4 minutes, passed away. His run on the Iffley track in Oxford in May 1954 was one of the defining athletic feats of the 20th century. In reading Bannister’s autobiography, however, it is striking just how much one man managed to pack into life, and how relatively little of it was concerned with athletic performance. He was an amateur athlete whose career pathway was already chosen, and that career was clinical medicine.

Sir Roger Bannister was a neurologist first and an athlete second. This goes some way to describing how good he was at neurology! He published 81 papers on the part of our nervous system that controls involuntary actions like breathing (called the autonomic nervous system). He also wrote and edited several texts on disease in this system.

Bannister’s investigations of the physiology of the respiratory system during exercise took place during a research scholarship in the University Oxford’s Laboratory of Physiology in 1951. It may surprise you to know that this had nothing to do with his interest in athletics. Bannister was instead interested in respiratory control, and exercise was merely a means of testing stress placed on this system. This work was published in The Journal of Physiology in 1954.

In this study, he explored the effect of oxygen levels on the movement of air in and out of the lungs (called ventilation), and on physical performance. To do this he had participants, including himself, run at constant speeds and breathe room air, with 33%, 66%, and 100% oxygen. At the time, the reason for the reduction in ventilation and improvement in physical performance when breathing oxygen-enriched gases was not clear.

Each of Bannister’s four participants is identified by initials, which is of course not allowed now. We know of three for certain (Bannister and his supervisor, Dr Dan Cunningham, who co-authors the paper, as well as Norris McWhirter [N.D.McW]). The latter was able to run with relative ease breathing 66% oxygen, and only terminated the treadmill test because “he had a train to catch”!

Throughout the paper, Bannister seems to interpret his results as a clinician: the participant’s subjective experiences of the tests seem almost as important as the respiratory variables themselves. In light of the sometimes extreme volume of data modern laboratory technology can produce, we shouldn’t forget to ask participants in physiological research how it felt.

Physiological research requires interactions with people in other ways too. In his acknowledgements, Bannister thanks, among others, Prof. Claude Douglas for help and advice. Where would exercise physiology be without Douglas? Everybody stands on the shoulders of giants. Even other giants do.

Sir Roger Bannister was special because he was an ordinary man who produced an extraordinary life’s work: on the track, in the laboratory, as a patron and administrator in sport and sports medicine, and in his clinical practice. His humanity shone through in everything he did, and his The Journal of Physiology papers are no different. Thanks for everything, Sir Roger.