Angus Brown, University of Nottingham

Never meet your heroes, the old adage advises us; they’ll inevitably disappoint you. Well, a brief, unexpected encounter with my hero was the highlight of my seventeen years at the University of Nottingham.

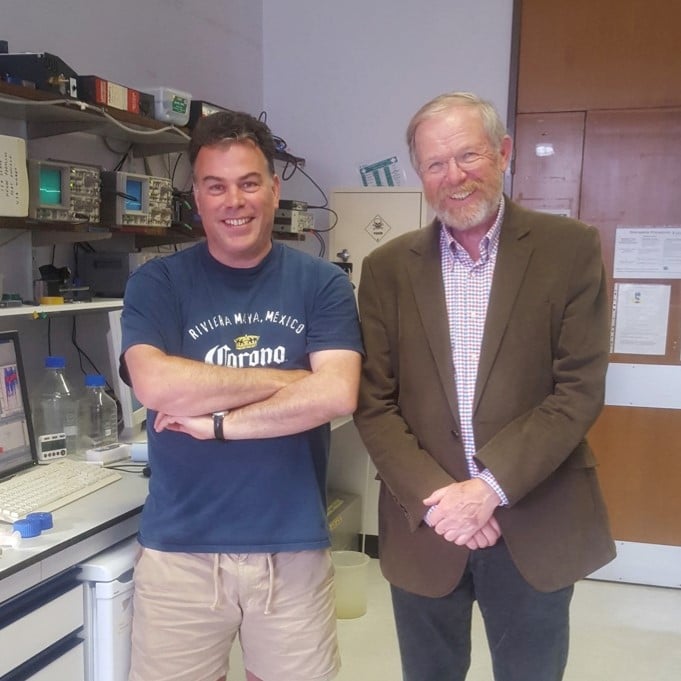

In my role as module convener for final year neuroscience projects I tutor students in various writing styles, with the expectation that this will instil an appreciation for good writing practices. I provide examples from classic literature including Gibbon, Camus, Garcia Márquez and more modern writers such as Bill Bryson, whose accessible prose does not draw attention to itself, but open any Bryson book and you’ll soon effortlessly find yourself on page fifty with a silly grin on your face. One Friday afternoon in summer 2017 I took a break from discussing Bryson’s book ‘Troublesome Words’ with my current Ph.D. student and headed to the tearoom. After a few moments who should enter but Bryson himself, instantly recognisable to the devoted reader in his tweed jacket and checked shirt. Enthusiasm overcame propriety and I fetched his book from my office. As I re-entered the tearoom a grin appeared on his face as he spied the book in my hand. He happily autographed the book, and we chatted for a hugely enjoyable thirty minutes, Bryson telling me that he was visiting the dissecting rooms at the Queens Medical Centre as research for his new book on the human body.

This book, entitled “The Body: A Guide for Occupants”, has now been published. It is in no way a physiology textbook, but rather a compendium of historically-aware facts relating to the wonders of the human body. Bryson has consulted an impressive cast of international medical experts, including a couple of my work colleagues, as his sources, whose expert knowledge and opinions add a welcome degree of rigour. The book systematically covers various organs, and then proceeds to the immune system, disease and medicines. It flows with Bryson’s easy style and amusing phrases, such as describing Wilbur Atwater, an early advocate of caloric measurements, as ‘no stranger to the larder’, and writing: ‘even allowing for the gusto with which my fellow Americans chow down’. A book such as this runs the risk of becoming the literary equivalent of a pub bore – a source of endless disparate facts. However Bryson is a master storyteller, constructing a narrative that builds throughout the book, with facts mentioned early on reappearing in an appropriate context later in the book. The historical aspect of the book adds a fascinating layer of interest, clearly demonstrating that the personalities of researchers drove their research in a particular direction.

Heroes, villains and just plain oddballs are all given space. The Nobel Prize-winning Nazi doctor, Werner Forssmann, and Japanese war criminal Shiro Ishii are duly noted, and the shabby treatment by Henry Gray of the illustrator Henry Carter of the famous anatomy book may encourage readers to view the book in a different light. The injustice of Selman Waksman’s acceptance of a Nobel Prize and pocketing the patent proceeds that rightfully belonged to his student Albert Schatz, is unfortunately not the rare event we would hope it to be, in the dog-eat-dog world of modern academia. The heroes include Karl Landsteiner who identified blood groups, facilitating advances in surgery, and Frederick Banting who discovered insulin, the true miracle treatment, which saves every child suffering from Type 1 diabetes a protracted and certain death. The death of Ignaz Semmelweis, who linked lack of hygiene to birth-related deaths from puerperal fever, is shameful. The strange characters that liven up the narrative include Brown Séquard, who advocated the rejuvenating properties of injection of ground-up dog testes, Michel Siffre, who isolated himself from the outside world for eight weeks to see the effects on perception of elapsed time, and Pierre Barbet who displayed a grim fascination with the effect of crucifixion on the human body.

I found the second half of the book particularly interesting in that it covered some surprisingly complex topics. For example, the distinction between population statistics (i.e. one person in six who smokes will develop lung cancer) and sample statistics (i.e. it is impossible to predict which individual smokers will develop lung cancer) are discussed. The advice about which foods are good/bad for you is a smorgasbord of confusion that Bryson relishes. Fat may or may not cause heart disease, but sugar certainly contributes. Too much salt is not as bad for you as too little salt if you have existing high blood pressure. Drinking water will revive those who are dehydrated, but drink too much and it will kill you. The fact I found most telling was this: the life expectancy of a male in the east end of Glasgow is fifty four. I am currently fifty four and can only thank good fortune that my parents moved from Glasgow to Dundee the year before I was born.

Bryson does not shy away from controversy, citing in excruciating detail the repercussions of the pelvic aperture diameter being one inch smaller than the emerging baby, as evidence for the lack of intelligent design. Similarly, the statistics on choking deaths are an indication of the disastrous consequences of food and air sharing the same inlet tube. The fate of Sidney Ringer’s daughter is another grim example of this tragic design flaw (1). The description of the removal of Pepys bladder stone is eye watering, emphasising that surely the greatest discovery of modern medicine is general anaesthesia. Bryson saves his wrath not for the austerity-driven rundown of the underfunded NHS of his adopted country, but for the excesses of his country of birth. The best way to ensure a long and healthy life is to be wealthy – no surprises there. However there is a startling caveat – unless you are American. All Americans, no matter their wealth, die sooner than their European counterparts. The reason for this is driven by the suicidal convergence of gluttony and entitlement, which leads to the paradox of the richest nation on earth with the most expensive healthcare having death rates akin to the developing world. The exorbitant cost of US healthcare is not reflected in patient care, but absorbed by administrative costs.

To summarise: those of us who consider Bryson our North Star, an ever-reliable harbinger of common sense in a chaotic world, will relish this book, its excellent index encouraging frequent revisiting of favoured topics.

References

- Miller, David J (2007). A Solution for the Heart: The Life of Sydney Ringer (1836-1910). Great Britain: The Physiological Society.