Physiology News Magazine

Numberism: exploring science through art

Features

Numberism: exploring science through art

Features

Sienna Morris

Artist

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.103.22

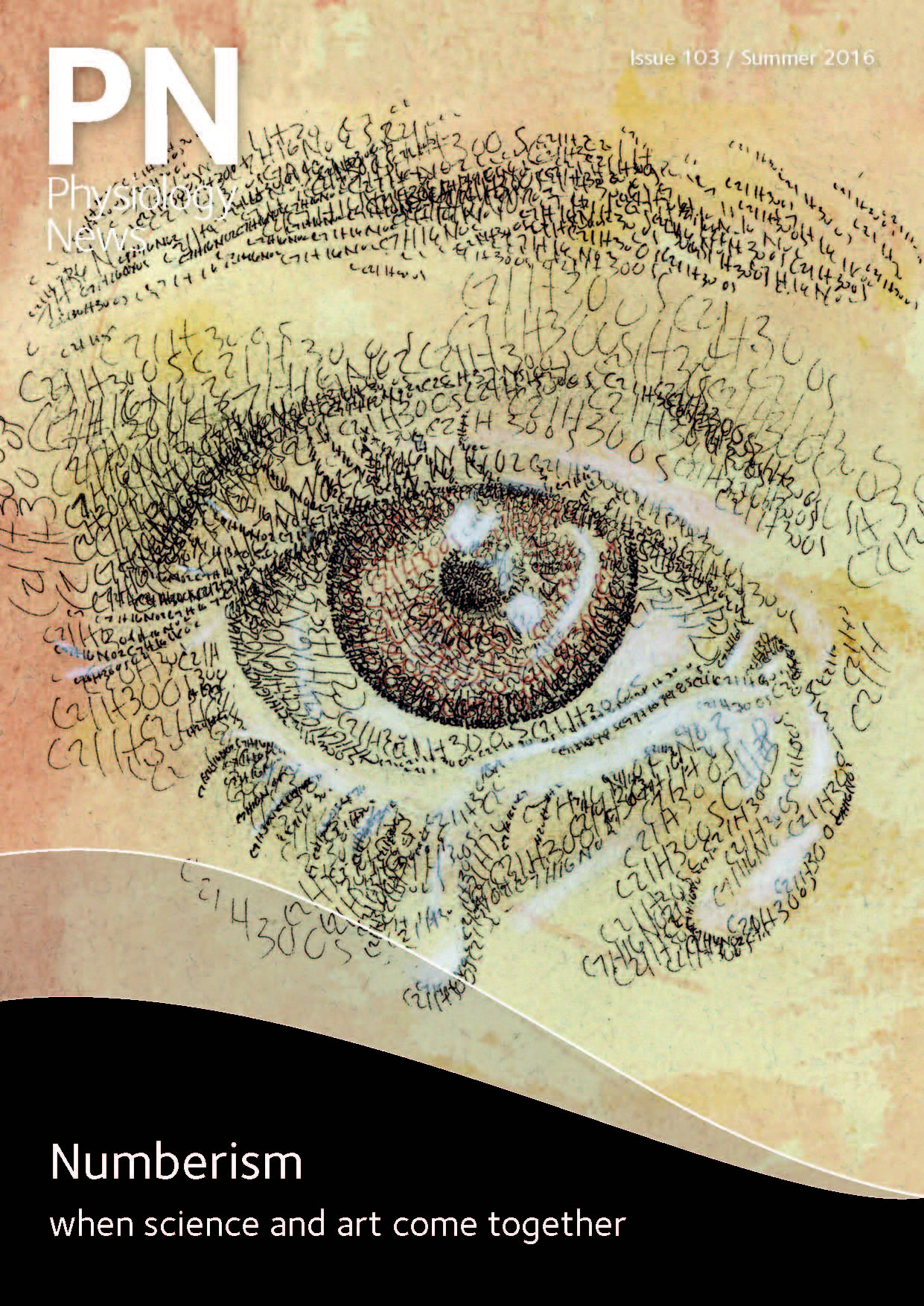

Sienna writes about her work as an artist using ‘Numberism’ – a technique in which she draws realistic images entirely with tiny numbers and equations by hand, using pen, pencil or as etchings on scratchboard, metal or glass.

I am a self-taught scientific artist in Portland, Oregon. I started using my drawing technique ‘Numberism’ as a learning device in 2008. This is similar to pointillism, which uses dots; however, my pieces tell a story of the subject using the scientific and mathematical language of their own structures to more clearly depict them. For me, the illustrations are more realistic and complete because they are drawn with mathematical representations of themselves. While my method utilises tools of academia, my process is visceral and driven equally by love and logic.

When I first started this series, I expected it would put people off, and prepared for the onslaught of ‘I hate maths’ comments to come my way. Instead, I found that by and large, people loved the excuse to celebrate the inherent beauty of math and science even if they themselves had no natural affinity for it. I describe my work as ‘drawing math where it lives’, a concept that strikes a chord with most people.

On average my pieces take around 200 hours to draw and upwards of a year to research. The ‘Heart’ (Fig. 1) took me seven months to draw, which was somewhere around 500 hours of ‘numberisming’. It is drawn with physiological equations such as stroke volume in the main body, cardiac output in the aorta, oxygen difference in the superior and inferior vena cava and oxygen content in the pulmonary veins. The remarkable ‘electric system’ of the heart is highlighted in the right atrium with the atrioventricular node drawn with its average firing rate and the sinoatrial node drawn with its membrane potential. This is part of an ongoing series on the body I am producing with a long-term goal of understanding the brain.

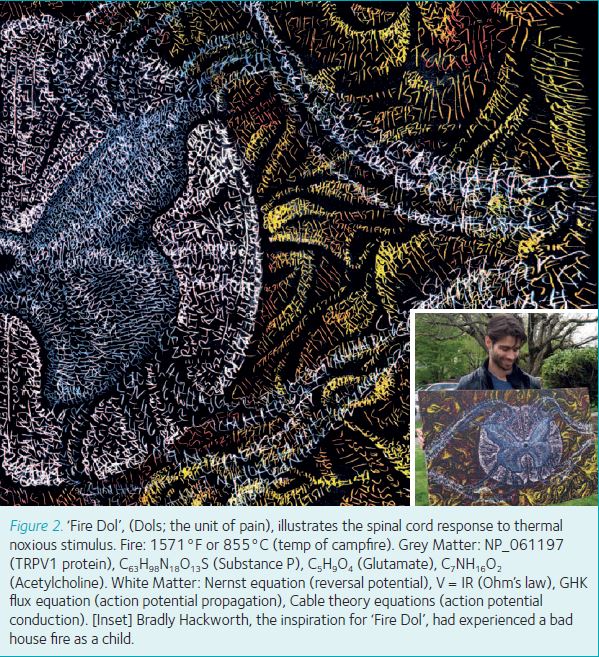

My latest work is ‘Fire Dol’ (Fig. 2), a story about the very first moments of experiencing the pain of heat. This is not the complex and largely unknown manner in which our brain processes pain, but rather the first reaction to the noxious stimulant, and how this information is transmitted from nociceptors in the spinal cord. It is drawn with the TRPV1 protein, chemical formulas for Substance P, Glutamate, Acetylcholine, reaction time for a reflex arc and equations relating to how action potentials from the dorsal and ventral horns are transmitted along myelinated axons to the brain and periphery. I have used Cable Theory, the GHK equation and Ohm’s Law to illustrate this, as well as The Nernst Equation and Membrane Potential for the initial Action Potential.

This piece in particular illustrates the personal mission of my work, in which I emphasise the beauty in systems often first seen as gross, scary, tedious or dull. I personally had the average American school experience with science and mathematics. The one that leaves you running and never looking back, full of sweaty palms and embarrassment. So, my work is aimed directly at those who have the most reason to despise it. ‘Fire Dol’ was my most difficult in this respect and perhaps the most rewarding.

My good friend Bradly Hackworth and his sister were in a bad house fire as children, which left long-lasting emotional and physical scars, and naturally a fear of fire. With ‘Fire Dol’, my goal was to illustrate the spinal cord’s response to thermal noxious stimuli so beautifully that even he, with his incredibly painful history, would find beauty and peace within it. The etching features the human spinal cord in transverse cross section over a field of hot flame drawn with an average temperature of a campfire. The scientific story is based on how nociceptors protect us, and how pain itself can preserve life by warning us against its source.

When Bradly first saw ‘Fire Dol’ he contacted me to say it was ‘the most beautiful finished piece yet’ and he was ‘in love with it’ (Fig. 2 – Inset). I’m ill equipped to describe how that moment felt. This rewarding connection through my work inspires me to create further pieces on trauma, recovery and the human mind. These will accompany ‘Psychic Tears’ (see Front Cover) which focusses on tears caused by emotional and physical triggers and is drawn with chemical formulas for cortisol and acetylcholine.

Science is hard

As someone who is self-taught, this can be overwhelming and potentially devastating to my education. I don’t have a professor to guide me, nor do I have classmates to commiserate with or compare notes. When I hit upon a wall and feel the full burden of my ignorance in these unexplored worlds, I must rely on my passion to get me through. I’m currently studying neuroscience with a focus on the visual system, so as you can imagine, I have hit upon many walls. As of yet, I have not faced a wall that could not be overcome by the inherent beauty of the subject, but I must first be able to find that beauty to be driven by it. It requires more than a sole reliance on textbooks and open-online courseware to see the beauty of the body and brain. I needed to experience it in the flesh.

This limitation led to an important change in my personal education and my artwork last year. Frustrated with my text-based education of a physical world, I launched a Kickstarter campaign to build a dissection lab in my art studio. My goal was to cover the basic costs by way of offering pre-orders of prints and originals from the planned series. In less than a day, it was 100% funded and by the end the campaign had collected an astounding $11,677 (583% of the initial funding goal). My ‘Art Lab’ now housed both a compound and stereo microscope, surgical tools, and a variety of specimens and histological dyes. I finally had the tools to delve deeper into the brain.

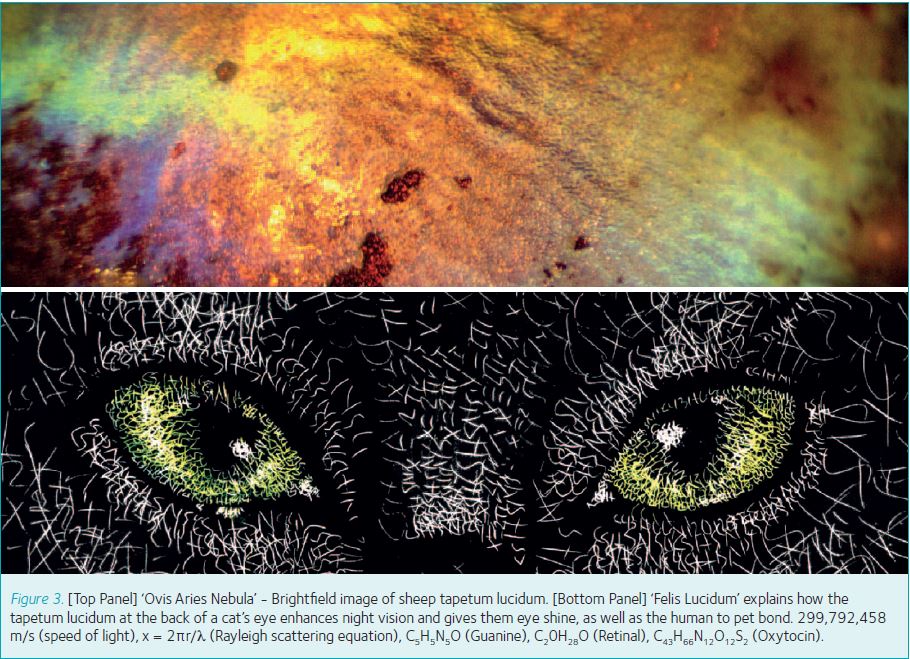

I made a mess of my first dissection, but found it truly fun and educational. In my first session, I dissected the eyeball of a sheep, cow and pig, dutifully separating the pieces onto Petri dishes to image later with my microscopes. I noted the difference between the viscous vitreous body and the fluid aqueous humour, tugged on the retina as it dangled from the optic disk, and twanged the clear zonular fibres suspending the lens. I felt like a child, enamoured and gloriously happy at the systematic mess I was making. I gathered up the rather foul smelling dishes and inspected them under my stereo microscope.

This is how I found the Universe at the back of a sheep’s eye; one of the first images I took with my stereo microscope (Fig. 3 – Top). It features the crystalline structure of the tapetum lucidum at the back of a sheep eyeball, found beneath the retina. I had read about these in my research into the visual system, but none of my books had featured an image. Looking down into my microscope, I was suddenly gazing up into the infinity above. After much illuminating research, I created two Numberism etchings based on the tapetum; ‘Felis Lucidum’ (Fig. 3 – Bottom) and ‘Lupus Lucidum’, both of which are drawn with chemistry and physics that explain how it allows for night vision and produces eyeshine.

This is the foundation of my method. I am driven into my research by beauty and confusion. My education is a love affair with curiosity. My notebooks are full of sketches of beautiful systems that I am compelled to later illustrate, like the Ventricles of the brain, the purkinje tree, and the mesencephalon. Words like ‘isoluminant’, ‘lacus lacrimalis’ and ‘arbor vitae’ read like poetry to me and serve as calls to arms to know them better and share them through my illustrations. My path isn’t very academic, although I embrace its virtues and methods. It is visceral and full of boundless admiration.

What I do does not come naturally to me, and without a mathematical background traversing these waters will never be easy, however that makes it all the more rewarding. I imagine that between us and the truth of the Universe is an infinite series of frosted panes of glass. Each new learning experience clears part of the frost of the nearest pane or removes it entirely. With an infinite set, we will likely never clear them all, but even reaching 100 panes closer to infinity is worth the effort. Being inspired by science means my palette can never go dry. Being self-taught means I understand my ignorance better than most and will therefore never be sated. As I will always be more unknowing than knowing, my journey will last a lifetime.

Further information

For more info on Numberism, Sienna can be found at the Portland Saturday Market (Oregon, USA) every Saturday and Sunday from March to Christmas Eve or online at the following:

www.fleetingstates.com

Etsy: siennamorris.etsy.com

Instagram: @SiennaMorris

Twitter: @MrsSiennaMorris

Facebook: facebook.com/numberism

Youtube: youtube.com/siennamorris