Physiology News Magazine

Stressed-out Britain? A report on our annual Theme and our survey

News and Views

Stressed-out Britain? A report on our annual Theme and our survey

News and Views

Lucy Donaldson

Chair of Policy & Communications Committee, The Physiological Society

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.107.16

Are British people as stressed as we all think? Everyone I talk to now mentions their busyness, the speed of life, and the expectation of immediate response or results. Has our stress really increased, and are the same things causing stress now as in the past? Are our parents correct in saying life was simpler and less stressful ‘when they were young’?

‘Life’s most stressful events’, such as getting married or moving house, are quoted time and again in the press. This list derives from the seminal work of Holmes & Rahe in 1967 that resulted in the Social Readjustment Rating Scale (SRRS). In this work, 43 life events previously correlated with the onset of illness were rated by over 5000 medical patients. Marriage was given the standard score of 500, and all other events were ranked in relation to it. The results form the basis for the ranked list of life’s stressful events quoted today. It’s worth noting that most, if not all items on this list are negative events (Holmes & Rahe, 1967).

The stress response is a distinct combination of bodily responses that enable us to cope with challenges. Without this response, such challenges could be life threatening. This is the physiologists’ take.

The ranked list defines stress as the feelings associated with a wide variety of situations, rather than the physiological definition. For most people, stress is a condition or feeling experienced when a person perceives that ‘demands exceed the personal and social resources the individual is able to mobilise’ (quote attributed to Richard S Lazarus).

Under our annual theme of ‘Making Sense of Stress,’ we are looking at stress in many different ways. We have public events, such as the lecture featuring Stafford Lightman, the topic meeting on The Neurobiology of Stress as part of the British Neuroscience Association’s Festival of Neuroscience, and virtual issues of our journals on stress.

As part of the annual theme, The Society’s Policy and Communications team took another look at the stress of people across the UK, in a broader group than just medical patients. We commissioned YouGov to survey over 2000 people in January of this year. Respondents rated a shorter list of life events according to how stressful they might find them (YouGov survey, 2016). We included some of the events from the SRRS as benchmarks, but also, after conversation with Professor of Health Psychology Kavita Vedhara of the University of Nottingham, we included some potentially positive events such as going on holiday or being successful at work.

Many of the key findings from the survey were not much of a surprise – going on holiday is the bottom of the list as we might expect, and just as Holmes and Rahe found. Similarly we would hope that success at work or being promoted would be a reasonably positive event, and (thankfully) it is close to the bottom of the list too. The events at the top of the list are hardly surprising either – death of a spouse or close relative was our benchmark for the most stressful event on the SRRS, but divorce has moved down the list relative to imprisonment or personal illness. This may be because divorce now carries less social approbation than in the 1960s. Planning a wedding has become relatively less stressful (the wedding planner is obviously worth it!).

Obviously, updating a study from decades ago afforded the opportunity to include some events pertinent to the 21st Century. Surprisingly, respondents said losing your smart phone is only marginally less stressful than the potential for terrorist threats, and more stressful than moving up the property ladder. Contrary to the picture painted in the media, Brexit is actually not very stressful for most people surveyed.

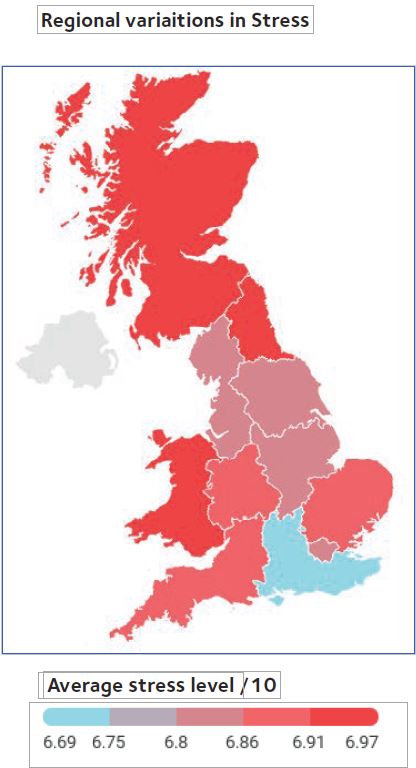

There are many more conclusions to be drawn from these data. For example, there is evidence that women report all these events as more stressful than men. Also, loss of your smartphone is more stressful for the younger generation (18–24) as is Brexit. There are also differences in responses to these different events across the UK. We hope to be able to examine the data in greater depth in a future issue of PN.

This YouGov survey obviously has limitations – it’s not a ‘scientific’ study and isn’t really directly comparable to the SRRS. It does, however, give us food for thought on how our perceptions of life’s stressors may have changed. We included many of the negative stressors in Holmes and Rahe’s list but also some potentially positive events. It is important to remember that stress can often be a positive experience. Hans Selye, often considered to be the first person to demonstrate the existence of biological stress, found that some stress can be good for you, but it depends on how you respond to the situation.

By motivating someone to tackle a challenge, stress can lead to feelings of satisfaction and accomplishment. It’s the spark that pushes us to do things we would normally not, and that extra encouragement is important, as without it, we would be complacent. Smaller amounts of positive stress – which Selye referred to as ‘eustress’ – have been shown to enhance cognitive abilities and boost mental prowess. This is because it helps us focus on the task at hand. Some studies have even shown that it boosts memory – which is really helpful when writing a grant proposal, preparing for your viva or marking to a deadline!

Rather than fearing stress, or always avoiding it, focus on harnessing it by believing in a good outcome and that you are in control. In his 1985 paper ‘The Nature of Stress’ (Selye, 1985), Hans Selye wrote about the importance of finding your own stress level to make sure that both the stress level and the goal are really your own, and not imposed upon you by society.

In closing, it is worth reflecting on the summary provided by Selye himself, ‘Fight for your highest attainable aim, but do not put up resistance in vain.’

References

Holmes TH, Rahe RH (1967). The Social Readjustment Rating Scale. J Psychosom Res 11(2), 213-8.

Richard Lazarus (1922–2002). Professor of Psychology, Emeritus, University of California, USA.

Selye H (1985). The Nature of Stress. Basal Facts 7(1), 3–11.

YouGov survey. All figures, unless otherwise stated, are from YouGov Plc. Total sample size was 2078 adults. Fieldwork was undertaken between 22 and 28 December 2016. The survey was carried out online. The figures have been weighted and are representative of all GB adults (aged 18+).