Physiology News Magazine

Science and politics

The 1923 International Physiology Congress in Edinburgh

Features

Science and politics

The 1923 International Physiology Congress in Edinburgh

Features

Fernando Cervero

Emeritus Professor, McGill University, Canada

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.107.33

‘La science n’a pas de patrie, parce que le savoir est le patrimoine de l’humanité, le flambeau qui éclaire le monde. La science doit être la plus haute personnification de la patrie parce que de tous les peuples, celui-là sera toujours le premier qui marchera le premier par les travaux de la pensée et de l’intelligence. Luttons donc dans le champ pacifique de la science pour la prééminence de nos patries respectives.’

Louis Pasteur, inaugural speech of the Pasteur Institute, 14 November 1888

The result of the Brexit referendum and the election of President Trump are largely due to increased nationalistic feelings in both the UK and the US, and there is evidence that these sentiments are also growing in other parts of Europe and the world. Nationalism has always had a challenging relationship with science, exemplified in extreme by the diaspora of German scientists under the Nazi regime; a mass exile which greatly benefited the receiving countries. As we are now being told that walls will be built and border restrictions will be imposed, it is worth having a look at how our predecessors dealt in the past with such problems.

In 1923, the 11th International Physiological Congress was held in Edinburgh at the invitation of the then Professor and Chair of Physiology of Edinburgh University, Edward Sharpey-Schafer. This was a major scientific event attended by more than 400 physiologists from all over the world (BMJ, 1923). These congresses, first started in 1889, were held every 3 years and led to the formation in 1953 of the International Union of Physiological Sciences (IUPS) (Schulz-Hofer, 2009). The 1923 congress was the second held in the UK, the first one took place in 1898 in Cambridge.

When I was a physiology lecturer at Edinburgh University in the late 70s and early 80s, I found, tucked away in the departmental library, a couple of cardboard boxes containing papers, letters and documents related to the organisation of the 1923 congress. Unfortunately, neither the Physiology Department nor its library exist today but some of the documents of the congress were transferred to the University main library where they have been safely kept.

Going through these records, it is intriguing to see how some things about congress organisation have not changed in the intervening decades whereas others are long gone, like the mention in the letter of invitation to the Lord Provost of Edinburgh that ‘we already have an entry

of close on 400, which does not include ladies accompanying members’. But among registration letters, requests of accommodation, invoices and other such papers, the documentation of the congress contains written evidence of a key political issue: should scientists from Germany and Austria be allowed to attend the congress?

The meeting took place 5 years after the end of the Great War, and feelings among some attendees were still raw. The sequence of physiology congresses had been interrupted by the war and was only re-established in 1920 with a congress in Paris that deliberately excluded physiologists from the recently defeated countries. For the 1923 congress, a passionate debate raged as to whether the barring of German scientists should still be maintained. The debate was fuelled by the threat of Belgian and French physiologists to boycott the congress if German scientists were allowed to attend.

The Edinburgh organisers, led by Sharpey-Schafer, wanted to have a truly international congress, stating that science is universal and that all scientists should be allowed to participate, meet and debate with their peers. They opposed any ban for reasons of nationality and invited physiologists from all over the world to come to Edinburgh. In the case of Sharpey-Schafer this was even more poignant as his two sons had been killed in action in the Great War. He had changed his name in 1918 from Schäfer to Sharpey-Schafer after his son John was killed at the battle of Jutland. ‘In our family we had to mourn the loss of my elder and only surviving son John Sharpey (Jack) … I decided to add the name Sharpey to my own name and duly advertised the fact. I did this partly on Jack’s account, partly because it was the name of my old teacher & master of Physiology (William Sharpey) – the best friend I ever had’ (Sharpy-Schafer diaries).

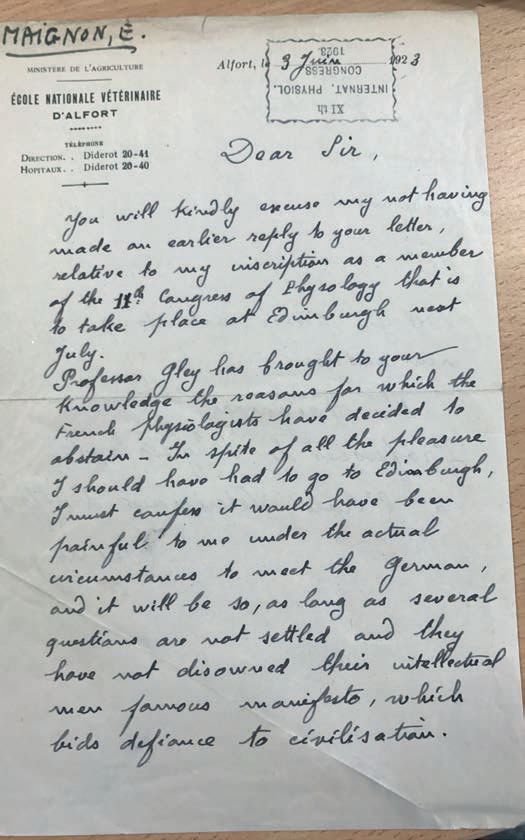

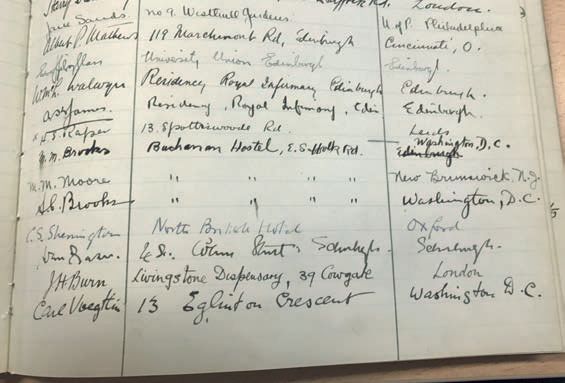

The American Physiological Society endorsed the aim of the organisers in a letter addressed to Sharpey-Schafer (Fig. 1) stating that ‘science knows no creed’ and extending their support to the organizing committee to ensure a truly international congress. However, French and Belgian physiologists were less forgiving and some decided not to attend the congress in protest for the presence of German physiologists (see Fig. 2). But in the end the congress was a success and was attended by la crème de la crème of contemporary physiology including Adrian, Banting, Bayliss, Dale, Einthoven, Frank, von Frey, Fulton, Gasser, Haldane, Hill, Houssay, Langley, Pavlov, Sherrington and Szent-Gyorgyi among others (see Fig. 3).

The congress papers contain some gems regarding the sensitive issue of the German delegates. Two letters from the Edinburgh Association for the provision of Hostels for Women Students include some interesting sentences regarding the accommodation that they were offering for congress delegates. In one of them they state that the hostels ‘will endeavour to divide the Germans from the French’ hoping that they would ‘understand a sufficient amount of English’.

In another communication they state that ‘the question of receiving guests from Germany and Austria was considered and it was unanimously agreed that no objection should be raised’. The letter also includes data on the accommodation charge: 8 shillings and sixpence (42.5p in today’s currency) per head per night for dinner, room and breakfast.

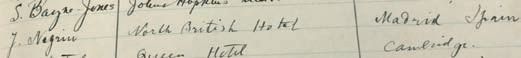

Aside from the German-French question the congress papers also contain some other bits of political relevance. One of the Spanish delegates at the congress was Juan Negrin, Professor of Physiology at the University of Madrid who later in life became finance minister in the Spanish Republic and was appointed Prime Minister during the Spanish civil war (Fig. 4). Negrin was a physiologist turned politician who unsuccessfully tried to save the Spanish Republic from the Franco onslaught and the brutal repression that followed (Preston, 2016).

On the scientific side, highlights of the congress included lectures from Ivan Pavlov – delivered by his son – on hypnosis and sleep, by Langley on the axon reflex and a keynote lecture by John Macleod from Toronto on recent research on insulin from his laboratory. Interestingly, Frederik Banting, co-worker of Macleod and co-discoverer of insulin, or perhaps just discoverer depending who you believe, was also attending the congress but Macleod got the limelight of the keynote lecture. Both were awarded the Nobel Prize in 1923 only a few months after the congress and there is a considerable literature as to the respective achievements of either of them as well as to the contributions of Charles Best to whom Banting gave half of his prize money and James Bertram Collip who in turn received from Macleod half of his cash (www.nobelprize.org/educational/medicine/insulin/discovery-insulin.html).

Turning back to the question of science and politics, it is refreshing to see the efforts made by Sharpey-Schafer and his committee as well as from organisations such as the American Physiological Society to ensure a truly international congress, to remove barriers imposed by nationality and to build goodwill among fellow scientists. His own personal tragedy did not prevent him from achieving this aim. A lesson to us all.

Acknowleldgements

My thanks to Dr Graeme D Eddie, Assistant Librarian, Archives & Manuscripts, Edinburgh University Library for finding the congress documents and to Tilli Tansey OBE for helpful advice and comments on this article.

References

British Medical Journal (1923). July 28, p. 142; August 4, p. 201; August 11, p. 256.

Schulz-Hofer I (2009). IUPS, a family of physiologists. int.physiology.jp/download/4736/file.pdf

EA Sharpey-Schafer diaries, Sharpey-Schafer Papers, Wellcome L., London, PP/ESS/S.1-3, S.2, S.3 (microfilm). http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/personExtended/mp04073/sir-edward-sharpey-schafer?tab=biography

Preston P (2016). The last days of the Spanish Republic. London: William Collins.

www.nobelprize.org/educational/medicine/insulin/discovery-insulin.html