Physiology News Magazine

Careers – no ‘one size fits all’ for scientists

‘What matters most is how well you walk through the fire’ -Charles Bukowski

Features

Careers – no ‘one size fits all’ for scientists

‘What matters most is how well you walk through the fire’ -Charles Bukowski

Features

This article was compiled by Jo Edward Lewis.

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.109.32

The career path of scientists is oft the result of happenstance; a chance meeting at a conference, a quirk in a dataset, a change in personal circumstance. There’s no one size fits all for scientists’ careers. We sought to highlight this with several case studies to encourage you on your way.

The winding road through research to medical school

Chloé Monnier

Medical Student, University of Nottingham, UK

I started studying biology and physiology fortuitously, in my hometown of Paris, at Université Paris VII Denis Diderot. It was rather uneventful except for the final years, which were punctuated by two summer internships at Northwestern University in Chicago. Before I knew it, I had completed a Master’s degree.

I wanted to go to medical school and was initially planning on applying to schools in the US. Someone mentioned the UK offhandedly and I ended up focusing my application on UK universities, as I was doing this in a bit of a rush to meet the October deadline. Knowing I had a whole year ahead and not wishing to remain in Paris, I contacted the Chicago research team I had worked with previously. I was lucky to get a post-baccalaureate research fellow position there that kept me busy up until the beginning of my medical degree in Nottingham the next year.

Coming from France, where the education is – in my opinion – great, but not really conducive to developing self-confidence and self-reliance, spending some time abroad and working in research was the best thing that could have ever happened to me. I learnt that it is okay to make mistakes as long as you learn from them; it is okay to not know as long as you look it up, and it is okay to ask people for help. I also learnt to rely on whatever knowledge and abilities I have to solve a situation, and trust that I can make it work.

I am grateful for the school of thought that is science. Spending a couple of years studying cell metabolism and working in research has taught me to think critically and analyse every angle of a problem thoroughly, work as part of a team and value every member of that team. It has allowed me to travel and make friends and colleagues for life from all over the world. Having studied and worked in France and in the US, and enjoyed aspects of life in both countries, I felt uniquely equipped to make the best of studying and living in the UK. I now enjoy the multi-cultural campus of Nottingham University and the opportunities I’ve been given here to learn and stay involved in research whilst pursuing medical studies.

Although mine has been a bit of a scenic route to reaching medicine, I would not trade it for the world; the scenery sure was worth it.

Collaborations are the lifeblood of science

Carlo Lisci

PhD student, Cagliari University, IT

I’m in the third year of my second PhD in Molecular Medicine. I came from Cagliari University, Italy. Thanks to collaboration between research groups, I have been at the School of Life Sciences, University of Nottingham for a year now, with Dr Preeti Jethwa and Professor Fran Ebling. Throughout my career, I’ve always been busy and interested in nutrition. My first PhD, which I received in 2014, concerned feeding and human nutrition. Attracted by experimental science, I now do most of my work in vivo using animal models, because I believe that observation of in vivo phenomena is critical to our understanding of physiology.

At Nottingham, we use a beautiful experimental model, the Siberian hamster. It’s a seasonal model of body fat, which demonstrates a long-day obese state (summer) and a short-day lean state (winter), associated with changes in food intake and energy expenditure. We are interested in a group of proteins called VGF-derived peptides which have been implicated in the regulation of energy balance. The collaboration began with Cristina Cocco, also from Cagliari University, and I now also work with Jo Edward Lewis.

We also collaborate with other groups and researchers at different universities. This is very important to me. The links between all the members of the research team are very fulfilling and stimulating. The various meetings in a serene environment allow true union between the members and the formation of new ideas, both short- and long-term.

My wish is to continue to create a link between these universities, to encourage high-quality science, as it should be in every nation on this planet. I wish you all, good science.

The beauty of science is it takes you across borders

Rebecca Dumbell,

Postdoctoral Training Fellow,

MRC Harwell Institute, UK

I completed my PhD from the Rowett Institute of Nutrition and Health, University of Aberdeen in 2014. The Rowett had merged with the University a few years before I joined, and combined with the rural location at the time, this meant that it still had the feel of a research institute. Towards the end of my PhD I heard about a postdoc position coming up at the University of Lübeck in Germany through word of mouth. In a bit of a whirlwind I flew out to Germany for my interview the day after submitting my thesis, and I started the job a few months later.

Getting set up in my new job and new country was a challenge. I quickly learned that I needed a lot of documents, all from different offices located very far from each other, and they all had to be collected in a particular order. My EU passport smoothed the process and made my experience much easier than what I witnessed my non-EU colleagues go through. Within 1 week I had everything I needed, including a place to live, a bank account, health insurance and a pension plan.

I spent almost 2 years as a postdoc in Lübeck and I really loved living in Germany. Half of my colleagues were German and the rest came from all over the world, all speaking English in the lab. This was a lot of fun and we set up things like ‘international cooking club’ and, my personal favourite, whisky club. I found that as the only native English speaker I was the go-to proofreader; this certainly improved my grammar if not the work I was checking!

I now work at the MRC Harwell Institute in Oxfordshire as a Postdoctoral Training Fellow, and again find myself in a research institute in a rural setting. This comes with its own advantages and challenges. I have to go out of my way to build on my undergraduate teaching experience. But, once identified, these issues are overcome by connecting with people at the nearby University of Oxford, and with my wider professional network.

For me the chance to work abroad is a big draw for a scientific career; it built my confidence and expanded my professional network as well as providing a great experience. Coming back to the UK was right for me at the time but I’d not rule out going abroad again.

American academia, and achieving a work–life balance

Chris Shannon,

Postdoctoral Research Fellow,

University of Texas Health Science Centre, USA

Upon finishing my PhD in human metabolism, I was confident that moving on to a different research environment would be the smart move. When undertaking the increasingly competitive task of finding a postdoc, it certainly helps if you’re not restricted to one geographical region. My initial criteria when postdoc hunting was simply that it should be 1) in a relevant field and 2) in a location that aligned with my active, outdoorsy lifestyle. I ended up in San Antonio, Texas – a large sprawling city where it’s too hot to go outside most of the year and too spread-out to walk anywhere when it does cool down! Needless to say, my initial feelings towards the city itself were somewhat negative, but my project was interesting and I tried to focus on making the best of the resources available.

This lab I joined represents the basic science arm of the broader Diabetes Division and, demographically, San Antonio is probably one of the best places in the country to study Diabetes. Here, I’ve been fortunate enough to learn about the disease from one of the world-leading clinical researchers in the field. Most of the work done in my lab involves cell culture or mice models, and I’ve consequently become accustomed to many new experimental approaches and techniques. The strength of the division in running clinical trials also means I’m able to continue working with human tissues, which can be invaluable in putting together impactful manuscripts. The lab is very well-funded, and my conditioned frugality towards consumables and experimental setups was (and still is) strongly discouraged! This level of funding also meant that I wasn’t initially expected to support my own salary with grant applications – a huge bonus when trying to be productive with experiments.

Despite the prevailing opinion about US academia, the work ethic at my institution seems fairly relaxed and people are granted substantial flexibility in their schedules. This probably isn’t representative of other labs in the US and certainly depends on the PI, who in our lab happens to be from the UK too (which explains the ritualistic group tea breaks). Most of the neighbouring research groups are similarly multinational, and it would be easy to work here without ever really experiencing Texan culture. Fortunately, I’ve had plenty of down time away from the lab and have gradually learned to appreciate San Antonio for the lifestyle it offers and rich culture it carries. For me, this has meant joining a local sports team through which I’ve developed an incredible network of friends. The transient nature of postdoc positions can encourage a tentative approach to organising one’s life when moving abroad, allowing you to engross yourself entirely in the job at hand. Establishing a life outside of work has been vital in putting my work here into perspective, and makes those inevitable scientific frustrations far easier to deal with.

Two careers-related reflections from a poacher turned gamekeeper

Richard Malham,

Senior Research Policy and Integrity Manager

orcid.org/0000-0002-9477-6488

There are two things I can’t stop banging on about whenever I have the chance to talk to researchers about careers. I like to think I’ve got a pretty robust perspective given that I have had the privilege of many perspectives on the issue: as a PhD student, working at the national level on careers policy (for biomedical researchers), and working at the University level on research policy that applies to a whole range of disciplines. The following are my personal opinions, and in no way reflect the position of any organisation I work, or have ever worked, for.

1. Be smart in the system as it is

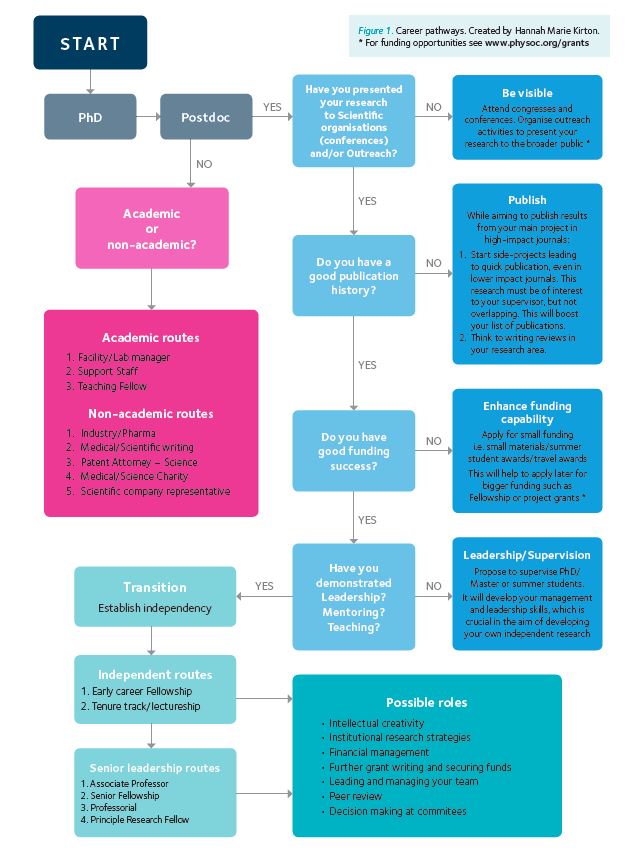

Make time to develop your career, don’t kid yourself that you will find time when we all know that there is always more you could do at the bench. If you stay in academia, having some demonstrable skills and experience beyond the bench, such as event organisation, public engagement, working with commercial partners, etc., will be a concrete advantage. If you move out of academia, they become a crucial advantage. Developing them requires proactively dedicating time, and may require you being assertive and unapologetic in the face of attitudes like (to paraphrase) ‘actively choosing to spend time away from the bench is heresy and a pointless distraction from the real work’. The return-on-investment is well worth sacrificing a fraction of your bench time: the stats on attrition are stark (American Society for Cell Biology, the Royal Society [Fig. 1.6 on p. 14] and Wellcome Trust[Fig. on p. 15]), so much so that the Royal Society released guidelines in 2014 for intervention at the PhD stage.

2. Simultaneously push for change

When you spot issues with career structures/opportunities, get organised at the grassroots level and engage employers and funders (what a great way to get that skills and experience as per point 1!). They care and are open to ideas, but bear in mind that i) not all change is possible because funding/jobs must be rationed because demand outstrips supply, ii) employers/funders are far more likely to push change ‘top down’ after new ideas have already started to be pushed from the ‘bottom up’ and iii) it’s not always their fault, so push in the right direction and don’t make unnecessary ‘enemies’. On the latter, do your research to find out where issues really come from: for example, issues you may have with funding and promotion decisions may actually be due to the behaviour of your fellow researchers (possibly even acting against institutional guidance) in their roles as peer reviewers and panel members, not by ‘the University’ as an organisation.

For those who feel that number 2 is too feeble, I’ll leave you with a suggestion: how about challenging the widespread assumption (underlying the design of various careers-related processes) that competition-based rationing is always best (e.g. www.timeshighereducation.com/news/universal-basic-income-better-option-research-grants). Or seek a completely different type of society…

The quest for the Holy Grail of lectureship

Gisela Helfer,

Lecturer, University of Bradford, UK

After I graduated in Zoology at the University of Salzburg, Austria, I worked at the Max Planck Institute for Ornithology in Andechs, Germany. Here I found my love for science in general and chronobiology in particular. From Andechs, I started my northwards journey, first to do a PhD at the University of Birmingham and then to postdoc at the Rowett Institute in Aberdeen. Throughout my journey, I was very fortunate to meet some amazing scientists, mentors as well as peers, and it was always my ambition to succeed in academia. Six years of postdocing, three moves and two children later, I finally found the Holy Grail in beautiful Yorkshire. In March 2016, I started my permanent lectureship at the University of Bradford.

Academia has one of the longest apprenticeships that I am aware of. Undergraduate studies, plus/minus masters studies, PhD studies and then several years of postdocing. For me, this totalled to 14 years of apprenticeship. Despite this long training, I was little prepared for the job of a lecturer. Yes, I had some teaching experience. I supervised students in the lab, I occasionally lectured to undergrads and I even worked a few months as a teaching fellow. In my CV I called this ‘extensive teaching experience’ – little did I know. Because in reality I spent all my days and often nights (the joys of circadian rhythms research) in the lab or in the animal house. And I loved every minute of it!

Now, I am rarely in the #Helferlab. The brand-new set of pipettes that I proudly bought from my first grant is now exclusively used by my students, while I spend my time rushing from place to place. I run to see undergrads or I run to one of my countless meetings.

I admit that I miss being a postdoc. I miss being in the lab from morning to evening, I miss having a supervisor who keeps me right (although my mentor at the Rowett is only a phone call away) and I miss the untroubled life of only being responsible for the next set of experiments. Of course, I do not miss the dreadful months before the contract comes to an end.

Despite all of this, I enjoy being a lecturer. While the holy grail is not as shiny and golden as I thought it would be, the journey was certainly worth it, and I would do it all over again. Next goal: professorship.

This article was compiled by Jo Edward Lewis.