Physiology News Magazine

Obesity – a global health crisis

News and Views

Obesity – a global health crisis

News and Views

Hannah Brinsden

World Obesity Federation

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.96.9

Barely a generation ago, our primary concern about global nutrition was linked to underweight, undernourished individuals. Today, whilst these problems continue to persist in many parts of the world, we are also faced with new health concerns about the rapid rise in obesity and non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as heart disease, diabetes and several diet-related cancers. Worldwide obesity has nearly doubled since 1980, there are more overweight adults than underweight ones, and it is now recognized as one of the most important public health problems facing the world today (World Health Organisation, 2013). Once associated with developed countries such as the USA, Australia and Western Europe, obesity and NCDs are increasing in every corner of the world, and most rapidly in low and middle income countries such as those in the Middle East and Latin America. Obesity affects adults and children, men and women, rich and poor and high and low income countries.

In response to this growing burden, the World Health Organisation (WHO) has set a target to halt the rise in obesity by 2025 (World Health Organisation, 2011) and there are many other policies and commitments to tackle this problem. However, to date, no country has yet been successful in reversing the rise in obesity. That is why The Physiological Society’s focus on obesity for 2014 is so important and relevant today.

Obesity and health

Obesity is a major cause of morbidity, disability and premature death, compared to smoking because of its associated disease burden and impact on population health. In 2008, around 1 in 4 adults worldwide were overweight (1.5 billion adults), of which 200 million men and nearly 300 million women were obese (International Association for the Study of Obesity).

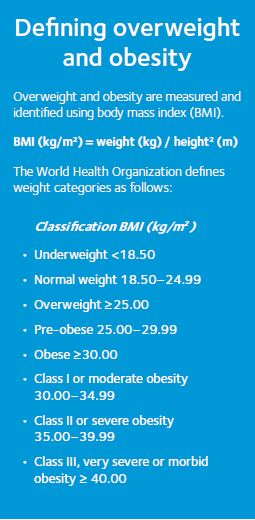

Body mass index (BMI) is a strong predictor of mortality among adults. Worldwide, the number of deaths from high BMI and physical inactivity was 6.56 million in 2010, more than that from tobacco (Lozano et al., 2012). Overall, moderate obesity (BMI 30–35 kg/m2) has been shown to reduce life expectancy by an average of three years, while morbid obesity (BMI 40–50 kg/m2) reduces life expectancy by 8–10 years. This 8–10 year loss of life is equivalent to the effects of lifelong smoking (Lancet, 2009). In the UK, obesity affects one in three adults in late middle-age (around 55–70 years old), and morbid obesity affects one in every 25 adults of this age (Health & Social Care Information Centre, 2014).

Obesity increases the risk of a wide range of chronic diseases. High BMI is thought to account for 60% of the risk of developing type 2 diabetes and 20% of hypertension and coronary-heart disease. There is also a strong link between body fatness and gall bladder, kidney, colorectal, ovarian, oesophagus, postmenopausal breast, pancreatic and endometrial cancers (World Cancer Research Fund International, 2014). This relationship is most likely due to the increase in the hormones insulin and leptin which is commonly seen in obese adults and thought to promote the growth of cancer cells. Other co-morbidities of obesity include raised cholesterol, fatty liver disease, sleep apnoea, heartburn, osteoarthritis and depression.

Of particular concern is the rise in obesity in vulnerable groups such as children and pregnant women. Global figures suggest there are more than 100 million obese women of child bearing age, with a further 250 million who are overweight (International Association for the Study of Obesity). Maternal obesity during pregnancy poses risks for both fetus and mother pre- and post-pregnancy. Obesity in pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of miscarriage, gestational diabetes, hypertension, pre-eclampsia, high risk labour, haemorrhage and maternal death. Maternal obesity can increase the risk of fetal distress, still birth (Schumann et al., 2014) and a ‘large for gestational age’ birth, which can increase the likelihood of labour and birth complications. High gestational weight gain can increase BMI of an infant later in life.

Over 200 million schoolchildren worldwide and more than 40 million children under the age of five were overweight in 2010 (International Association for the Study of Obesity). Childhood obesity is associated with an increased risk of disease later in life and it has been predicted more than three quarters (77%) of obese children become obese adults (Freedman et al., 2001). Obese children have been found to have increased risk of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, raised blood cholesterol, metabolic syndrome and fatty liver disease (Lobstein & Jackson-Leach, 2006, Reilly et al., 2003).

The economic and social burden of obesity

Obesity presents a significant financial burden to individuals, health services and the economy, both directly and indirectly. It has been estimated that the average obese person costs 36% more in medical care than healthy weight people (Thompson et al., 2001). Direct medical costs include the preventative, diagnostic and treatment services related to overweight and associated co-morbidities, while indirect costs include income lost from decreased productivity, reduced opportunities and restricted activity, illness, absenteeism and premature death. The cost of obesity is rising with estimates suggesting it was responsible for about 9% of total healthcare spending in 2003, on average across OECD countries, up from just 5% some 30 years earlier. In the USA it now exceeds 16% of the national health care budget (OECD, 2011). In the UK, the healthcare costs attributable to overweight and obesity are projected to double to £10 billion per year by 2050 with the wider costs to society and business estimated to reach almost £50 billion per year (Butland et al., 2007).

There is also a problem of prejudice against obese individuals resulting in issues of stigma, both within the general population and within healthcare services. This in turn can lead to depression and low self-esteem, which can affect an individual’s quality of life, mental health, educational achievement and employment prospects. Prejudice found among health service staff can also put obese people off seeking treatment or continuing with treatment they have started.

The multiple drivers of obesity

The UK government’s 2008 Foresight report described the ‘complex web of societal and biological factors that have, in recent decades, exposed our inherent human vulnerability to weight gain’ (Butland et al., 2007). According to the ‘thrifty gene hypothesis’ the genes that helped our ancestors survive are the same genes that are causing obesity. While there is a direct link between genes and obesity in conditions such as Bardet-Biedl syndrome and Prader-Willi syndrome, many obesity genes are only expressed in the presence of obesity-promoting behaviours such as sedentary behaviour and/or high energy intake, and the environments that promote such behaviours.

Unfortunately the lack of a single definitive cause of obesity means there is no quick fix solution. We must therefore work together, in our respective areas whether that is in research, policy, prevention or treatment, to try to get to grips with this epidemic. Preventing obesity through policies that address the environmental drivers, particularly food environments that promote diets high in fat, sugar and salt (Monteiro, 2011, Frazao, 1999) is essential, but health care professionals also play an important role in providing patients who are either already overweight or obese, or at risk of becoming overweight, with advice on weight loss programmes and treatment options such as surgery and drugs, something that World Obesity’s education programme SCOPE is working to support health professionals with.

It is not impossible to tackle this health problem – weight loss of just 10% can bring about significant improvements in co-morbidities -but we all need to do our bit and act now.

More information about obesity and the World Obesity Federation can be found at www.worldobesity.org, or why not follow us on twitter @worldobesity

References

Butland B, Jebb S, Kopelman P et al. (2007). Tackling Obesities: Future Choices – project report. Foresight: Government Office for Science, URL www.foresight.gov. uk/Obesity/17.pdf.

Frazao E (ed) (1999). America’s Eating Habits: Changes and Consequences. USDA Economic Research Services, Washington DC.

Freedman DS, Kttel-Khan L, Dietz WH & Srinivasan SR (2001). Relationship of childhood obesity to coronary heart disease risk factors in adulthood. Bogulusa heart Study. Pediatrics 108, 712–718.

Health & Social Care Information Centre (2014). Statistics on Obesity, Physical Activity and Diet – England, 2014. URL Healthhttp://www.hscic.gov.uk/article/2021/Website-Search?productid=14291&q=obesity&sort=Rel evance&size=10&page=1&area=both#top.

International Association for the Study of Obesity. Data Portal. URL: http://www.iaso.org/resources/obesity-data-portal/resources/trends/.

James WP (1995). A public health approach to the problem of obesity. Int J Obes 19 (suppl3), S37–S45.

Lobstein T & Jackson-Leach R (2006). Estimated burden of paediatric obesity and co-morbidities in Europe II: Numbers of children with indicators of obesity related disease. Int J Pediatr Obese 1, 33–41.

Lozano R et al. (2012). Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 380, 2095–2128.

Monteiro C (2011). Commentary. The big issue is ultra-processing. There is no such thing as a healthy ultra-processed product. World Nutrition 2, 333–349.

OECD (2011). Health at a Glance 2011: OECD Indicators, OECD Publishing, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/health_ glance-2011-en.

Prospective Studies Collaboration. Body-mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900 000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies.

Lancet 2009, 1083–1096.

Schumann, NL, Brinsden H & Lobstein T (2014). A review of national health policies and professional guidelines on maternal obesity and weight gain in pregnancy. Clinical Obes (in press).

Reilly JJ, Kelner CJ, Alexander DW, Hacking B & Methven E (2003). Health consequences of obesity: systematic review. Arch Dis child 88, 748–772.

Thompson D, Brown JB, Nichols GA, et al. (2001). Body mass index and future health-care costs: a retrospective cohort study. Obes Res 9, 210–218.

World Cancer Research Fund International. Summary of the latest findings for all cancers linked with greater body fatness. http://www.wcrf.org/cancer_statistics/lifestyle_factors/summary_of_the_latest_findings_for_all_ cancers_linked_with_greater_body_fatness.php.

World Health Organisation (2013). Fact file: 10 facts on obesity URL: http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/obesity/en/.

World Health Organisation Global recommendations on physical activity for health (2011). URL http://www.who. int/dietphysicalactivity/physical-activity-recommendations-18-64years.pdf.