Epidemiological evidence and animal models provide strong evidence that poor early growth is a risk factor for late life cardiovascular disease, stroke, hypertension and type 2 diabetes (Barker, 1995), but the mechanisms involved in the correlation between onset of adult disease and in utero nutrition are unclear. A commonly used animal model to study these effects is the offspring of the rats fed a low protein diet during pregnancy and lactation. In this study, we investigated growth of Wistar rats born to mothers fed a low protein (8 %) diet (LPD rats) or a normal protein (20 %) diet (NPD rats) ad libitum beginning 2 weeks prior to mating and continuing throughout gestation and lactation were investigated. Litters were culled at birth to 8 pups per dam and litters weaned by 28 days to the normal protein (20 %) diet. Body weights of offspring were measured weekly up to 24 weeks. Organ weights were taken at 3 or 12 weeks. Rats were anaesthetised I.P. with hypnorm (0.4ml kg-1) and hypnovel (0.4ml kg-1), heparinized (100, 000 U kg-1 I.P.) and humanely killed. Organs (brain, heart, lungs, spleen, pancreas, liver, kidney and adrenal glands) were removed and their dry and wet weights were measured at 3 and 12 week of age.

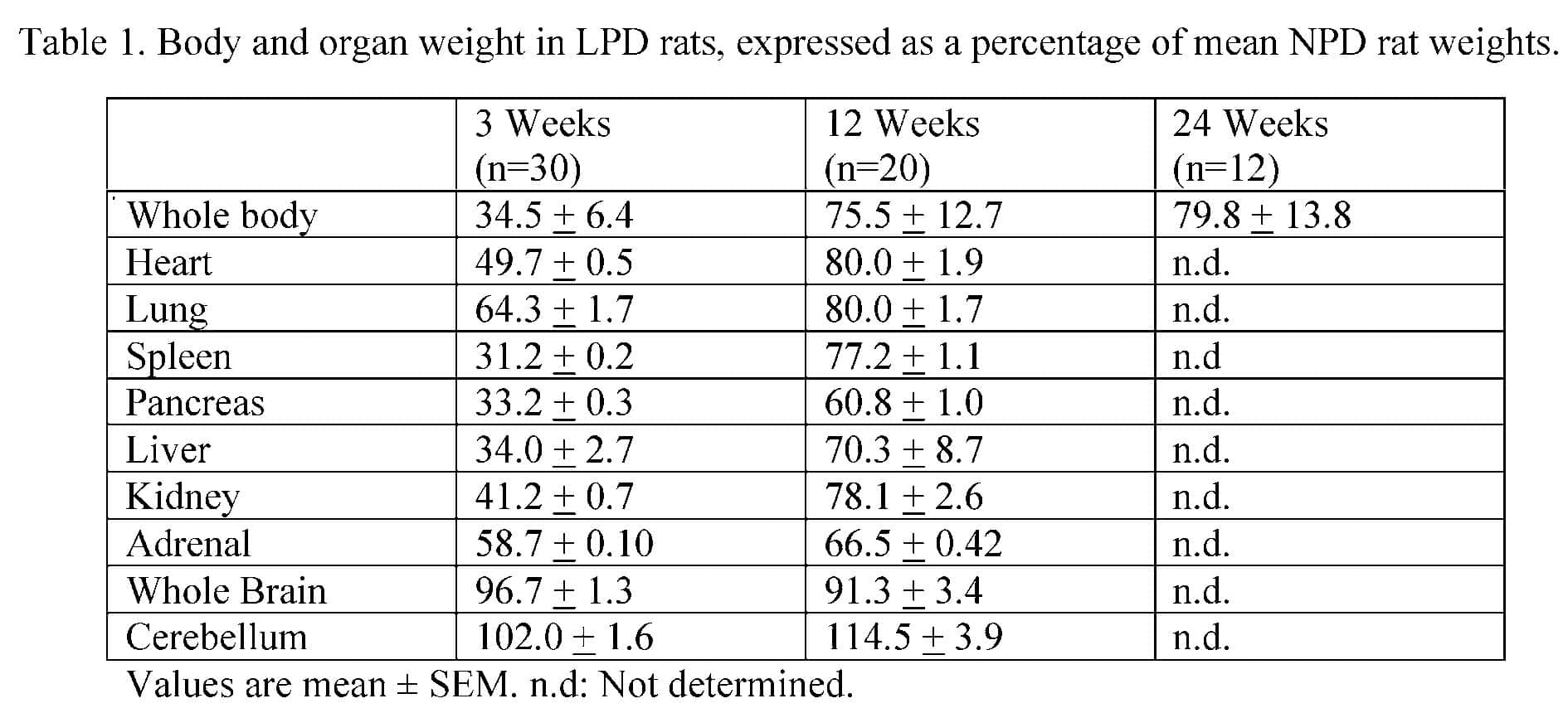

Weights of the LPD rats were significantly lower than for NPD rats at 3 and 6 weeks (P < 0.001) and some catch up of body weight was observed after weaning to normal protein diet (Table 1). However significant disparity of weights were remained at the adults at 12 weeks and remained at 24 weeks (P < 0.05, Table 1). These results suggest that growth of the offspring is consistently retarded and not fully recovered upon feeding with balanced diet after weaning in this model. Deficiencies in growth of all organs was seen when compared to NPD rats, except whole brain and in particular the cerebellum. Most organs demonstrated proportional catch up growth in adulthood including the kidneys, which contrasts with other models. However, two endocrine organs, the pancreas and adrenal gland remained disproportionately small, and to a lesser extent the liver, which has implications for poor glucose tolerance and control of blood pressure in adulthood.

This work is supported by the British Heart Foundation