By Gladys Onambele-Pearson, Manchester Metropolitan University, UK and Kostas Tsintzas, the University of Nottingham, UK

Why is exercise physiology particularly prone to self-labelled gurus? It may have to do with the widespread use of social media and the rise in striving for a so-called ‘athletic’ looking body and ‘optimal’ eating. Personal trainers, be it formally trained exercise scientists, or enthusiasts and celebrities with little formal training, are establishing themselves as the voice of authority. They speak out on exercise protocols, enhancing lean body definition, and optimising nutrition in training regimes.

These gurus highlight the benefits of healthy eating over indulging in a poor diet, and of exercising in a manner that minimises boredom, to avoid being sedentary. They are very enthusiastic, passionate even, about their message, utilising a wide range of media (Facebook, personal blogs, Twitter, Instagram) to reach their audience and clients. They will speak in terms that are easily assimilated by the majority, respond promptly to queries, and only sometimes cite scientific literature to support their claims.

Case in point: branched chain amino acids

Of particular concern, is the fact they will often simplify a large body of scientific evidence. A case in point is a quote from a guru to the effect that branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) will improve your physical performance and reduce muscle breakdown, thus enhancing exercise recovery. This statement is succinct, hence attractive to the general public. It is, however, not entirely accurate.

There is a lack of evidence for the performance-enhancing effects of BCAA supplementation before or during exercise (Bishop, 2010). There is also inconsistency in their effects on muscle soreness experienced hours or days after strenuous exercise, and on the recovery of muscle function following exercise (Jackman et al., 2010; Shimomura et al., 2010). It is true that BCAA cause changes in muscles after acute exercise. However, there is no compelling evidence connecting events observed at the cellular or molecular level after acute exercise with adaptations over time (enhanced performance, recovery, or muscle growth) following a prolonged period of physical training.

Learn from exercise gurus’ online engagement

Exercise gurus’ maintenance of the rapport with the audience, for example through addressing each member directly by their name, is striking. They also often follow the audience’s progress through the ‘body perfect lifestyle’ journey, supporting them with positive comments and encouragements via individual emails. Their reach is wide, indeed many counting their communities, or subscribers, in the tens and even hundreds of thousands. This is many more than scientific papers would normally dream of directly reaching!

What’s more, the training regimes advocated often can cater to one who uses a gym, prefer outdoors exercise, or prefer equipment-free workouts in their own home. Together with regular ‘check-ins’, this arguably increases adherence to lifestyle changes.

Academics and social media

We would argue that research physiologists in academia tend not to engage directly with the public in this way. When researching healthy eating, we are aware of, and would present the pros, the cons, and the limitations of any recommendation that our published data highlights. Where we disseminate our findings publicly, it will primarily be through scientific journals in a language that would automatically alienate a large segment of the population through its academia-specific terminology.

Where we do disseminate to lay audiences, our message is always tempered, as we are (rightly) unwilling to make conclusions appear definitive. This then has the counter-productive result of leaving the layperson unsure of what actions to take from our message.

Although only a minority of researchers engaging fully with social media, the general trend is for increased recognition of the need to engage in this way to make more people (scientists and lay public alike) aware of our findings. An increasing number of scientists are using Twitter to disseminate their publications and build their network of colleagues (and occasionally showcase their vanity). However, this engagement is still tentative as there are no academic institutions that reward their scientists for the number of Twitter or Instagram followers, or indeed hits on their Facebook page or online blog. It is of critical importance that scientists develop specific communication skills to enable them to convey their messages in a way that can be easily assimilated by the majority and then applied to everyday life.

Exercise scientists should become the new exercise celebrities

So practically speaking, how can we work against the misinformation by exercise gurus? In trying to answer this, we thought about the following: How do they check on the veracity of their statements? Are they happy to use anecdotal reports as evidence? What formal qualifications do they have to enable them to formulate these exercise programs and nutrition/supplementation protocols, or is life experience adequate enough in this context?

Indeed if we are looking at the average member of the public who exercises little if at all, what good is it to them to understand the difference between training at longer muscle length versus shorter muscle length (Eugene McMahon et al., 2013)? The first thing they should consider is the need to exercise on a regular basis, particularly when starting from a baseline of high habitual sedentary behaviour. If another member of the public eats a poorly balanced diet, what good is it for them to distinguish between the benefits (or otherwise) of correctly timing their intake of various micronutrients? They should first understand how their habitual diet can be realistically tweaked to be more healthy. These latter thoughts would probably explain why the simplistic approach of the ‘exercise guru’ appeals to the lay audience.

We would propose there is an inverted snobbery against social media for physiology researchers and the tide may be for the turning. In an era of ‘alternative facts’, it is our responsibility that the true (scientifically-evidenced) message is made public rather than allowing rampant myths to be propagated and not challenged by those with access to the wider public, who are, in the end, our target audience. We are in a privileged position whereby a lot of our research can and does have direct application pipelines and as such should reach the end-user directly from us.

To do so, we will need to acquire the communication skills necessary for the creation of ‘true science’ blogs, with the type of enthusiasm, responsiveness, and application of ‘results’ promoted by the exercise gurus which will then give the public what it deserves: nuanced recommendations based on systematic and reviewed evidence. For instance, teaching that where supplements are concerned they should be exactly that: supplements and not substitutes for other food stuff.

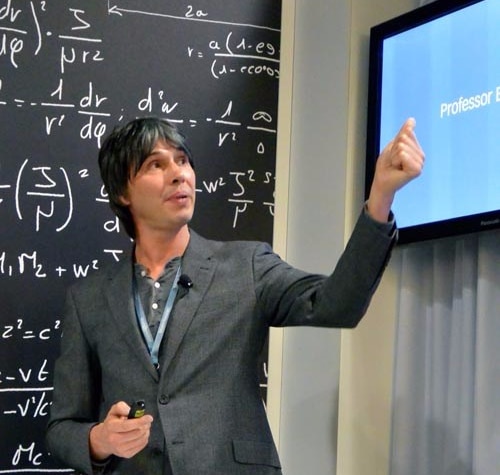

Is the correlation between tweets and citations around the corner? In an era where celebrities become self-styled ‘exercise gurus’, it’s time, as Brian Cox has recently proclaimed, for scientists to become celebrities themselves.

A longer version of this article was originally published in Physiology News.