James Pawelczyk, NASA astronaut, Physiologist at Pennsylvania State University

Fifty years ago, humans landed on a planetary body for the first time. Three years later, the Apollo program ended. The longest time on the lunar surface? Three days.

Relegated to low earth orbit by mission and hardware, subsequent programs – the US Space Shuttle and the International Space Station – enabled impressive scientific strides. We now understand much more about the conditions necessary for humans to thrive as planetary explorers. Thanks to the ISS, humans have been living continuously off of our planet for nearly 19 years; the longest stay being 340 days. An entire generation has grown up with the understanding that a human presence in space is the norm.

Yet one profound question continues to vex scientists, blocking our progress to colonize other planets. All life that we know evolved with Earth gravity. Does biology require Earth’s gravitational field? Or, can organisms as large and complex as humans adapt successfully to gravitational forces different from Earth’s?

We’re poised to leave low earth orbit and begin to tackle this fundamental scientific problem. The Artemis Program, announced by NASA earlier this year, will place the first woman and the next man on the lunar surface in 2024. With its relative proximity to Earth and a gravitational field only 1/6 that of Earth’s, the lunar surface is the perfect location for fractional gravity laboratories.

In Greek mythology, Artemis is the twin sister of Apollo. The name of the program – like the composition of its first crew – signifies our promise that space exploration is gender-inclusive. But the Artemis program bears little resemblance to its Apollo predecessor. Enabled by the Space Launch System – the most powerful rocket ever created – and the Orion spacecraft – a joint American and European venture – Artemis will deliver tons of equipment to the vicinity of the Moon and eventually Mars. The first launch is less than a year away. In less than 10 years, women and men will live on the Moon for months at a time.

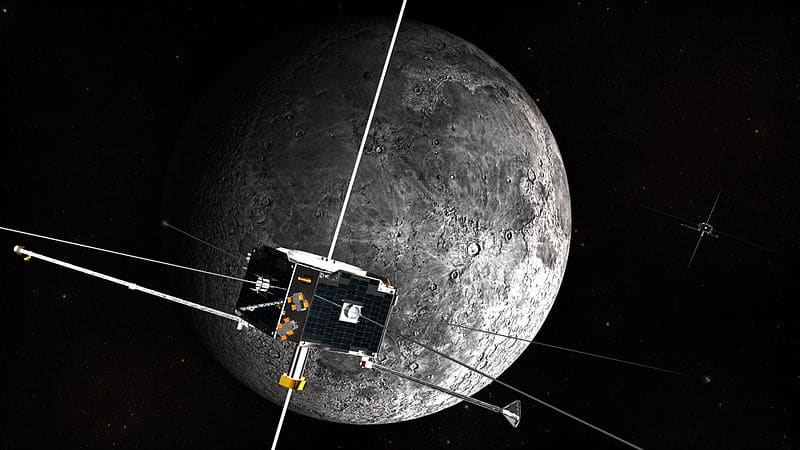

Artemis will place a transfer station, or Gateway, in the vicinity of the Moon. With purpose-built spacecraft shuttling from Earth to the Gateway, and from the Gateway to the lunar surface, the Moon will be the testing ground to perfect the technology, skills and techniques for future exploration of Mars and other planets.

Commercial partners are essential to develop the next generation of lunar landers, focusing on a sustained human presence at the lunar south pole within a decade. This unprecedented government-commercial partnership will involve a third partner: scientists with a thirst to study and utilise the lunar environment for research.

Late last year, a team of University and NASA researchers published direct evidence that frozen water is mixed in the lunar regolith in the cold, permanent shadows of craters at the poles. These areas hold special intrigue for lunar geologists and biologists alike. Eventually, this ice might be used to sustain residents of the Moon.

This early focus on research emulates expeditions to Earth’s polar regions a century ago. The flexibility of the Artemis architecture presents opportunities to deploy landers specialized for scientific disciplines, like a lunar vivarium to house cell cultures and model organisms ranging from yeast to rodents. A sustained presence on the Moon means that breeding colonies can be established, allowing biologists and physiologists their first opportunity to determine whether mammals can successfully adapt and evolve to different gravitational conditions over generations. A comparable “life cycle” experiment was first completed on the space station Mir with plants more than 20 years ago, but has never been attempted with mammals.

This is heady stuff. If it seems more fantasy than fact, please know that the rocket is now being assembled in Louisiana for the first Artemis mission next year. The first contracts for the Gateway have already been released, and companies like Blue Origin and SpaceX are competing their designs for lunar landing systems.

We are returning to the Moon as a stepping stone to the future exploration of Mars. Determining if mammals can reproduce successfully on the Moon will set the stage for sustainable colonization of the planets, another step for humankind that will inspire ours and future generations.