By Associate Professor Rebecca E Campbell, University of Otago, New Zealand, Twitter: @RECampbell_inNZ

As a PhD student in the late 1990’s I heard the phrase “committing career suicide”. This emotive and insensitive phrase was associated with women pursuing an academic career in science choosing to have children.

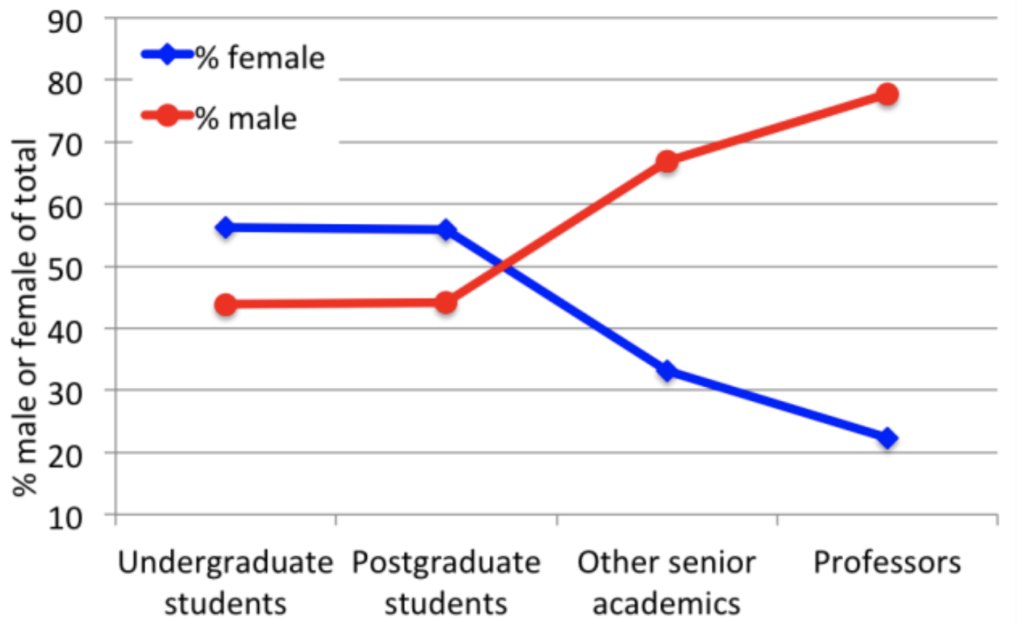

Although there were some truly inspiring exceptions in my midst, my environment at that time largely supported the rhetoric. Women were well-represented as graduate students and postdoctoral fellows, but were sorely underrepresented in academic positions, particularly at the highest levels.

We now understand that several factors contribute to this so-called scissor plot phenomenon which plagues STEM, not the least of which is unconscious bias, but motherhood was touted as the obvious and avoidable factor driving the sloping number of women in tenured positions.

Despite encountering this, I wasn’t willing to accept that motherhood and a scientific career were mutually exclusive, so I decided to take this “career limiting” path… twice. Today, I can gratefully report that I am still in the academia game, with two amazing kids and a career that I am proud of. I feel incredibly honoured to be at a stage in my career where I have opportunities like serving as a Senior Editor for Experimental Physiology and as a council member for the Physiological Society of New Zealand.

I can confidently say that I am a better mother because of my work and I am a better researcher because I am a mother. However, this perspective has only materialised with time and experience and I wish I could have given my younger self a few encouragements along the way!

My view is very different now, having aligned myself with supportive allies that are walking a similar road, and also witnessing really positive advances in support for women in STEM over the last 20 years. However, I still commonly encounter questions from female trainees in my field about how to reconcile family life with a scientific career, or how to do that colloquial juggle.

I certainly don’t have all (any!) of the answers and everyone’s path is unique, but I think it is important to share our stories in order to normalise the integration of a scientific career with motherhood.

When I think about the critical elements that have either supported or hindered my path, they tend to fall into two categories: those that have to do with tangible things like support, and those that have to do with less tangible things like mind set or expectations, both my own and those of others.

Support (the institutional kind)

The bottom line is that you need this. We all have limited time, energy and, well, arms. Our peak years for fertility coincide with the busiest times in our research careers. This means trying to raise a family while also trying to build a reputation, secure a position, establish independence and achieve tenure or confirmation.

The reality is that you cannot be everywhere at once and you cannot meet everyone’s needs all the time. Accepting that you are human and have limitations is the first step to being able to ask for help and access support where it is available.

Unfortunately, access to support, such as paid parental leave and affordable childcare, is highly variable between countries and institutions and can dramatically affect the experience, or even feasibility, of combining motherhood and academic science.

I consider myself incredibly fortunate to have had generous paid parental leave periods and an affordable childcare option that was literally just outside my office window.

I found this support fundamental to both the practical and emotional aspects of trying to thrive in my roles as academic and mum. I counsel others to know what is available, to not be shy about asking for institutional support, and to advocate anywhere possible to ensure that greater resources are available for those coming up behind us.

In order to access the incredible potential and talent of women in STEM, governments and institutions need to be thoughtful and proactive about supporting working parents.

Support (the people kind)

I’ve found personal support networks to be equally important. My husband likes to joke (to the rolling of my eyes) that the secret to my success was marrying well… Granted, he is an amazing husband and father and I couldn’t do what I do without him, but he also works full time in a career that he is equally passionate about.

This means that we’ve needed a village bigger than just ourselves to raise our children. We were intentional about building that support around us, and I am forever grateful to the loving assistance of family and friends and childminders that we brought into our home.

They not only enabled us to attend to the demands of our jobs, they also gave our children different experiences and unique perspectives of the world.

The non-tangible things like expectations and bias

While a working father will rarely be questioned about his fitness as a parent or his commitment to his career, working mothers seem to be fair targets in this arena.

On my son’s first day of school I met another mother who, after I mentioned my job, explained that she had been a working mum for a while but then left work because she felt like she was being a bad mother.

I encountered this not-so-subtle assumption that at-home mothers are superior to working mothers on a regular basis, while also engaging in a competitive academic environment that promoted equally damaging perceptions and messages in the opposite direction.

The idea of motherhood as ‘career limiting’ for women suggested that as a mother I would not be able to handle the pressure and commitments of an academic career and that I would likely fail, that a working mum is too torn and not single minded enough to be successful in academic science

I found myself feeling like I needed to parent as if I didn’t work and work as if I wasn’t a parent, but this only led to isolation and feelings of not achieving in either area, much less both.

Over time, I learned to tune out those unhelpful messages and to focus on the value of my own unique path, knowing that it might look different from the outside, but that it is mine and that it works for me and my family.

I’ve written grants and papers at the playground (and the pool, and the library…). I’ve brought babies, then young children then tweens and teens into my office to play, write on the white board and do homework.

I’ve left meetings and work commitments when my kids have needed me and then made up for it in the hours when everyone else was sleeping. It’s been messy and anything but single-minded, but I love it.

Reconciling family life with a scientific career is not new and there are millions of other stories out there. I acknowledge that I stand on the shoulders of giants who came before me – brave, inspirational women who paved a smoother path for me.

I am often inspired by two-time Nobel Prize winner Marie Curie who not only had a daughter, she raised a daughter who also won the Nobel Prize. We need to drop the messages about what women can’t or shouldn’t do and celebrate all the incredible things that we can do with the right backing and support.