by Michelle Pizzo & Robert Thorne, University of Wisconsin Madison, USA

The brain and spinal cord are a difficult body parts to fix. Only seven percent of drugs for diseases of the brain and spinal cord succeed, whereas fifteen percent of drugs for other parts of the body do (1). New research published in The Journal of Physiology may have found part of the solution: a method for getting bigger drugs into the brain.

The issue is, in part, that we still lack a detailed understanding of the complicated structure and physiology of the brain’s cells and fluids, including the communication between the cells and fluids (2). This limited knowledge has further compromised our understanding of the delivery and distribution of drugs in the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord, abbreviated as CNS), particularly for large-molecule drugs (bigger than about one nanometer) which are unable to cross the blood-brain barrier to reach the brain tissue.

A tight fit: getting big antibody drugs into tiny brain spaces

Among the best examples of promising large-molecule therapeutics are antibodies, the weapons of our immune system. They work by recognizing a part of a molecule (called an antigen). Indeed, five of the top ten drugs by revenue are antibodies (3).

Besides being great potential drugs, antibodies are very abundant in the fluid that bathes the brain and spinal cord (called cerebrospinal fluid, or CSF) (4). Antibodies in the CSF may play an important role in the brain’s immune system and contribute to central nervous system autoimmune disorders (like multiple sclerosis) that cause our immune system to attack our own body.

Because antibodies (and other large-molecule protein therapeutics) are 10 times the size of small-molecule drugs, it has long been thought that their distribution in the brain will in most cases be much more limited than small-molecule drugs (5).

However, a recent study published in The Journal of Physiology from the University of Wisconsin-Madison by Michelle Pizzo, Robert Thorne, and their colleagues (6) has uncovered an unappreciated key mechanism governing antibody transport within the CNS that may ultimately allow these big proteins to access much more of the brain from the CSF than previously thought.

This has important implications as there are numerous clinical trials that are ongoing in the United States for treatment of brain cancers with antibody drugs.

Go with the flow: using the fluids of the brain for antibody drug delivery

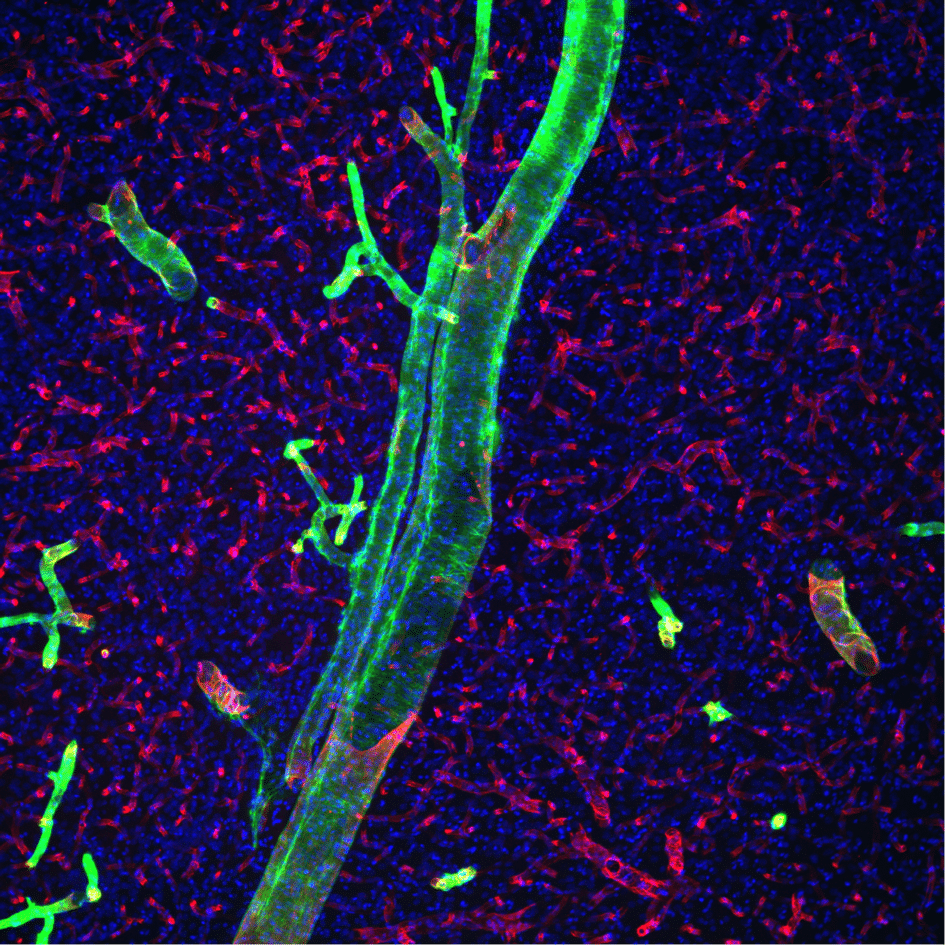

Injecting antibodies of two different sizes into the CSF of rodents, the researchers found two main mechanisms of transport—1) slower movement (called diffusion) in between the tightly packed brain cells, and 2) quicker transport along tubular spaces around blood vessels, (called perivascular spaces) (6).

As expected, they found that the slower movement of these large molecules by diffusion was quite limited, whereas the smaller antibodies penetrated further. Aspects of the quicker transport around the blood vessels appeared to be independent of size; both the smaller and larger antibodies could reach deep into the brain along the walls of blood vessels in a short amount of time.

This is great news for the CSF delivery of biotherapeutics, including protein drugs like antibodies. The quicker perivascular flow along these tubular pathways is thought to exist in humans, so such flows are likely translatable/scalable to the clinic. Slower, diffusive transport, on the other hand, does not scale across species. In other words, if effective drug diffusion is limited to a distance of one mm in the rat brain, it will also be limited to one mm in the much larger human brain. This distance may not be enough to treat most brain diseases.

They also found that the smaller antibody was able to get into more of these tubular perivascular spaces compared to the larger antibody, which meant a significantly poorer overall delivery was obtained for these full-sized antibodies. Two questions arose from this finding—1) what barrier is causing this size-dependent entry into the perivascular space, and 2) can the barrier be altered to improve delivery?

Let me in: identification of a new barrier between the CSF and brain and a strategy to open it

Pizzo and her colleagues found that a layer of cells wrapping around blood vessels on the surface of the brain, between the CSF and the perivascular spaces, is a likely candidate for the size-dependent barrier.

They suggested that pores or openings in these cells may contribute to a sieving effect, allowing smaller molecules into the perivascular space but making entry more difficult for larger molecules. A method that has previously been used to open cell barriers is to administer a hyperosmolar (which more or less means, concentrated) solution that makes these cells give up their water to dilute the surrounding solution. Thus the water exits the cells (by osmosis) and causes them to shrink, allowing gaps between cells and pores in the cells to open. Pizzo and colleagues then reasoned that if they were to administer this solution into the CSF, the larger antibodies would enter the perivascular spaces better.

This is essentially what they found; the larger antibody had significantly greater access (about 50%) to the perivascular spaces when it was delivered into the CSF with a hyperosmolar solution.

Numerous studies of protein drugs administered into the CSF are ongoing for brain cancer and childhood metabolic diseases that affect the brain (called neuropathic lysosomal storage disorders). Thus, an improved understanding of how these large molecules move through the brain is critical.

This new research has shed light on how these antibodies use different types of transport to move between the CSF and the brain in rodents, revealing that fast perivascular transport can reach deep into the brain and may offer the best hope for translation to humans.

Even more exciting is their new hypothesis for the cellular barrier that may regulate entry into these perivascular spaces. Manipulating this ‘barrier’ could lead to improved methods for delivery of drugs to the brain and spinal cord.

References

- Pangalos MN, Schechter LE, Hurko O (2007) Drug development for CNS disorders: strategies for balancing risk and reducing attrition. Nat Rev Drug Discov 6(7):521–32.

- Thorne RG (2014) Primer on Central Nervous System Structure/Function and the Vasculature, Ventricular System, and Fluids of the BRain. Drug Delivery to the Brain: Physiological Concepts, Methodologies, and Approaches, eds Hammarlund-Udenaes M, de Lange E, Thorne RG (Springer-Verlag, New York), pp 685–707.

- Lindsley CW (2015) 2014 global prescription medication statistics: strong growth and CNS well represented. ACS Chem Neurosci 6(4):505–506.

- Davson H, Segal MB (1996) Physiology of the CSF and blood-brain barriers (CRC Press).

- Wolak DJ, Thorne RG (2013) Diffusion of macromolecules in the brain: implications for drug delivery. Mol Pharm 10(5):1492–504.

- Pizzo M, et al. (2017) Intrathecal antibody distribution in the rat brain: surface diffusion, perivascular transport, and osmotic enhancement of delivery. J Physiol:Accepted manuscript.