Ellen McGarity-Shipley

Cardiovascular Stress Response Lab, School of Kinesiology and Health Studies, Queen’s University

When I was studying physiotherapy, there were several times that I noticed healthcare professionals shaming patients for different health risk factors like smoking, being overweight or not having a healthy diet. After watching a particularly intense moment where a doctor was shaming a patient for smoking, it occurred to me: could shaming patients cause physical harm?

Shame and society

When I looked at the current research on how shame affects human bodies and health, there was a very small body of research. This made me realise that even though we regularly use shame to try to change people’s behaviours, you can see this everywhere in parenting, school, sports, healthcare practice, public health campaigns, even some advertisements, we do not have a good understanding of how shame affects people’s bodies. This is a big problem and what inspired me to explore the impact of shame on human bodies and health.

Stigma can enhance the sense of shame

One of the main sources of shame in our society is stigma. Stigma happens when a society identifies a group of people as being bad, e.g. “people who are overweight are lazy, irresponsible, and unmotivated” 1-4. Just because a stigma exists does not mean everyone in that society accepts it as being true. Unfortunately, it is generally recognised as a common belief. It is well-known that stigmatised people have worse mental health5-7 but some research has also found that there are physical health effects like increased blood pressure 9, signs of diabetes onset10, and risk of cardiovascular disease11.

Increased shame is a potential reason why stigma has these health effects since people who are stigmatised tend to have higher amounts of shame12-18. Shame itself has been associated with lower self-rated health19 and shorter lives among HIV/AIDS patients20, 21. However, a lot more research is needed to fully understand the relationships between stigma, shame, and health.

How do you investigate shame in the lab?

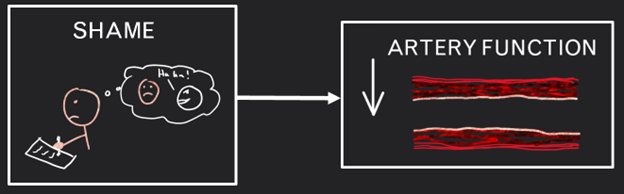

We carried out our study by taking several physical measurements before and after people were “shamed”. This was to analyse fitness and energy levels, heart rate, blood pressure and hormone levels. To shame people, we asked them to write about the most shameful experiences of their lives for 20 minutes. We specifically wanted to know how shame impacts the function of arteries; the blood vessels that carry blood from your heart to the rest of your body.

We assessed artery function by measuring how much an artery widens after a big increase in blood flow. Artery function is important because properly functioning arteries prevent plaque build-up, the cause of many different cardiovascular diseases such as heart attacks 22-24.

How shame causes physical harm

Our main finding was that shame temporarily decreased the function of people’s arteries, and individuals who felt the most shame had the biggest decrease in artery function. To try to explain why this happened, we also measured a stress hormone, an inflammatory hormone and blood pressure. Shame did not change stress or inflammatory hormone levels but it did increase people’s blood pressure. We think this means that shame increases the “fight-or-flight” response, which narrows the arteries and impairs their function.

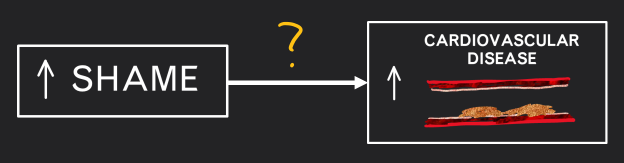

Increasing the risk of heart disease

Since we found that shame temporarily decreased artery function which is important to prevent plaque build-up and cardiovascular disease 22-24, this suggests that people who frequently experience a lot of shame may have increased risk of developing cardiovascular disease. People in stigmatised groups would be particularly vulnerable, but this would also apply to anybody who is regularly shamed by their parents, teachers, coaches, healthcare professionals, or even by media and social media.

Do public health campaigns need a new approach to encourage behaviour change?

This was the very first study to look at the short-term impact of shame on artery function and so these findings do need to be further investigated and confirmed by other studies. Studies could also explore how shame might temporarily affect the body in other ways. To fully understand the short- and long-term impact of shame on cardiovascular health, it would be important for future studies to use large datasets that have data stretching over long periods of time.

If findings continue to show that shame is bad for our health, researchers should also investigate whether stigmatised health risk factors, such as heavy body weight, have a negative impact on health partially because of the stigma and high levels of shame the individual experiences. If this is the case, it would suggest that stigmatisation and shaming strategies that are sometimes used in public health campaigns and healthcare practice are more harmful and counter-productive than we think. An alternative approach to influence health behaviour-changes may be needed in future.

To find out more about the study and the results, read the full research paper published in Experimental Physiology.

References

- Dolezal L, Lyons B. Health-related shame: An affective determinant of health? Med Humanit. 2017;43(4):257-263.

- Goffman E. Stigma and social identity. Understanding deviance: Connecting classical and contemporary perspectives. 2561963. p. 265.

- Parker R, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: A conceptual framework and implications for action. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(1):13-24.

- Stangl AL, Earnshaw VA, Logie CH, et al. The health stigma and discrimination framework: A global, crosscutting framework to inform research, intervention development, and policy on health-related stigmas. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):31.

- Mak WW, Poon CY, Pun LY, Cheung SF. Meta-analysis of stigma and mental health. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(2):245-261.

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(5):674-697.

- Cochran SD. Emerging issues in research on lesbians’ and gay men’s mental health: Does sexual orientation really matter? Am Psychol. 2001;56(11):931-947.

- Muennig P. The body politic: The relationship between stigma and obesity-associated disease. BMC Public Health. 2008;8(1):128.

- Matthews KA, Salomon K, Kenyon K, Zhou F. Unfair treatment, discrimination, and ambulatory blood pressure in black and white adolescents. Health Psychol. 2005;24(3):258-265.

- Tull ES, Sheu Y-T, Butler C, Cornelious K. Relationships between perceived stress, coping behavior and cortisol secretion in women with high and low levels of internalized racism. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97(2):206.

- Everson-Rose SA, Lutsey PL, Roetker NS, et al. Perceived discrimination and incident cardiovascular events: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;182(3):225-234.

- Keltner D, Gruenfeld DH, Anderson C. Power, approach, and inhibition. Psychol Rev. 2003;110(2):265-284.

- Walker R, Bantebya-Kyomuhendo G. The shame of poverty. New York, NY: Oxford University Press 2014.

- Sedgwick E, Frank A. Touching feeling: Affect, pedagogy, performativity. Durham, NC: Duke University Press 2003.

- Farrell A. Fat shame: Stigma and the fat body in American culture. New York, NY: NYU Press 2011.

- Harris-Perry M. Sister citizen: Shame, stereotypes, and black women in america: Yale University Press 2011.

- Brown-Johnson CG, Cataldo JK, Orozco N, et al. Validity and reliability of the internalized stigma of smoking inventory: An exploration of shame, isolation, and discrimination in smokers with mental health diagnoses. Am J Addict. 2015;24(5):410-418.

- Evans-Polce RJ, Castaldelli-Maia JM, Schomerus G, Evans-Lacko SE. The downside of tobacco control? Smoking and self-stigma: A systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2015;145:26-34.

- Lamont JM. Trait body shame predicts health outcomes in college women: A longitudinal investigation. J Behav Med. 2015;38(6):998-1008.

- Cole SW. Psychosocial influences on HIV-1 disease progression: Neural, endocrine, and virologic mechanisms. Psychosom Med. 2008;70(5):562-568.

- Dickerson SS, Gruenewald TL, Kemeny ME. When the social self is threatened: Shame, physiology, and health. J Pers. 2004;72(6):1191-1216.

- Inaba Y, Chen JA, Bergmann SR. Prediction of future cardiovascular outcomes by flow-mediated vasodilatation of brachial artery: A meta-analysis. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;26(6):631-640.

- Matsuzawa Y, Kwon TG, Lennon RJ, et al. Prognostic value of flow-mediated vasodilation in brachial artery and fingertip artery for cardiovascular events: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4(11):e002270.

- Ras RT, Streppel MT, Draijer R, Zock PL. Flow-mediated dilation and cardiovascular risk prediction: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168(1):344-351.