By Simon Cork, Neurophysiologist, Imperial College London, @SimonCorkPhD

According to a 2016 survey of 2000 people in the UK, almost two thirds of us are on a diet at any one time. For most people, the typical diet consists of eating a salad for lunch, and cutting out desserts and snacks. NHS guidelines for weight loss recommend reducing calorie intake by around 600 calories each day. But is this advice right?

There is a theory among many scientists in the obesity field that body weight is fixed around a “set point”. That means that for the majority of people, body weight is typically static (unless drastic changes are made to exercise or diet). Any fluctuations in our body weight are compensated for by either increasing or decreasing energy input or output. You might feel this if you’re on a low calorie diet by feeling constantly tired and feeling like you just want to sit down. That’s your body’s way of trying to conserve energy.

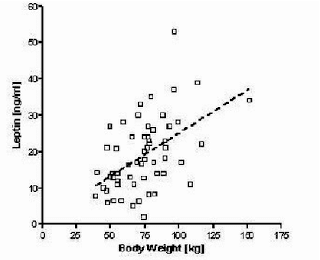

One method our body uses to keep its weight constant is a hormone called leptin, released by fat cells into our bloodstream. The more fat we have, the more leptin we have flowing through our blood. Normally, leptin acts in the brain to restrict appetite, effectively acting as the brake to restrict major changes in body weight. Minor increases in fat lead to increases in leptin, which reduces appetite. Loss of body fat causes decreases in leptin and thus increases in appetite to compensate. Leptin is therefore the body’s messenger to the brain, informing it of our weight.

The problem occurs when we override the effects of leptin, typically with respect to its appetite-restricting effects. More fat means more leptin, which should reduce our appetite, and thus reduce our body weight back to what our brains perceive as “normal”. However, if we override these effects (e.g. by ordering dessert after starters and a main, or eating large portions, thus eating past the point of feeling full), our brains eventually become resistant to leptin.

This leptin resistance effectively means that our brains are tricked into underestimating what our body weight truly is. Although a 150 kg person has more circulating leptin than a 70 kg person, the extra leptin doesn’t decrease appetite as it should because the brain has become resistant to leptin: it needs more leptin to have the same effect. The brain is therefore “tricked” into thinking the body has less fat than it really does.

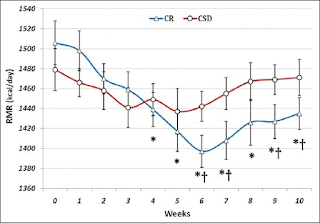

This has significant consequences when people who want to lose weight go on low calorie diets. As we restrict food intake, we lose body fat. For reasons not fully understood, the levels of leptin fall at a greater rate than body fat. Our brains react by activating mechanisms to restrict any further loss of body fat and promote energy storage. One such reaction is lowering the resting metabolic rate – effectively the minimum amount of energy required to keep us alive.

You may remember a US TV series called “The Biggest Loser”. This show took overweight or obese people and subjected them to a gruelling exercise and diet regime. The contestant who lost the most weight by the end of the show won a significant cash prize. In 2016, the results of a study were released which followed the contestants after they finished the show. They found that almost all contestants regained their weight and found that some regained more weight than before they started.

And this is the crux of the matter. It has been found that people who go on crash diets significantly reduce their resting metabolic rate – effectively, they are using less energy just by being alive than before the diet. And this metabolic rate may never recover – even after stopping the diet.

This may explain why a number of contestants regained more weight after the show than they started with. Their bodies are constantly fighting against a famine. It may also be why most people who go on a diet fail to maintain their low body weight long term. This is the key issue that many people developing weight loss therapeutics are facing.

For many people, losing weight is relatively easy. Simply restricting calories and/or increasing the amount of energy we use, usually by exercising, will result in weight loss. Maintaining that weight loss is the key issue. Exercise is often the key to maintaining weight loss, but is difficult to maintain the necessary levels of exercise required to compensate for the decreases in energy use that occurs following dieting.

Scientists are currently investigating how to manipulate the body weight set point, by both re-sensitising the body to leptin (i.e. countering the leptin resistance), and/or by increasing the levels of naturally occurring hunger-suppressing hormones that our bodies release after eating.

If decades of dieting advice has told us anything, it’s that dieting doesn’t work to bring about long-term weight loss. But importantly, by permanently reducing the resting metabolic rate, dieting may actually be preventing our bodies ability to lose weight in the future.