Physiology News Magazine

34th International Congress of Physiological Sciences: from molecule to malady

At the end of August over 2000 physiologists attended the 34th IUPS Congress in Christchurch, New Zealand. Here John Lee and Austin Elliott report from the other side of the world.

Features

34th International Congress of Physiological Sciences: from molecule to malady

At the end of August over 2000 physiologists attended the 34th IUPS Congress in Christchurch, New Zealand. Here John Lee and Austin Elliott report from the other side of the world.

Features

Austin Elliott

School of Biological Sciences, University of Manchester

John Lee

Consultant Pathologist, Rotherham District General Hospital

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.45.8

Christchurch, New Zealand, August 26 – 31, 2001

Welcome to Christchurch

First off, Christchurch is just such a nice place to hold a meeting. Everyone who has been to New Zealand will understand. For those of you who haven’t, here are some of the reasons why. The people are delightful, amazingly friendly and incredibly helpful. Rush hour in the city centre typically equals all of three cars at a traffic light. The meeting facilities are excellent and within easy walking distance of everywhere you want to be. There is an excellent arts centre and a real buzz of life around the many shops, coffee houses and eateries. And yet, compared to the normal tempo of European life, every day feels like a Sunday afternoon. Plus, with three New Zealand dollars to the pound and prices that are approaching (though not quite) pound for dollar, you can live comfortably for quite a modest outlay. Alternatively, you can spend what you would normally spend and have a few days feeling substantially more like Mr or Ms Big than is usually possible, especially when travelling.

And some background

The city of Christchurch in the South of England sits on the river Avon and, funnily enough, so does the one in New Zealand. But this turns out to be one of those situations where the obvious explanation is wrong; in fact, neither the city nor the river is named for its English counterpart. The city is named after Christchurch College in Oxford, where one of the original settlers’ leaders was educated, and the river (we have it on good authority) is named after the Avon in Scotland, rather than the English one. Strolling along the picturesque riverside walk-ways, it is thought-provoking to see the old pictures on historical placards showing that only 150 years ago there was no city here at all. Even more thought-provoking is the view from the Christchurch gondola (cable car), high up on the edge of the volcanic Banks peninsula. From here you can appreciate that just a few hundred thousand years ago the whole area was underwater, not to mention thirty or forty miles offshore. Erosion from the spectacular Southern Alps, which can be seen sparkling in the distance, has created (and continues to expand) the vast, flat expanse of the Canterbury plains, where Christchurch now sits a few miles from the sea.

Incidentally, this exhaustive background research was carried out over the weekend before the meeting. And we want you to appreciate the considerable dedication of your correspondents in acquiring it, suffering as we were from – inter alia – sore lower legs, shortness of breath, mentally incapacitating jetlag, a tendency to speak backwards, and stomach pain that should have been due to taking aspirin to fend off deep vein thrombosis (except that we forgot to take it).

On to the Conference

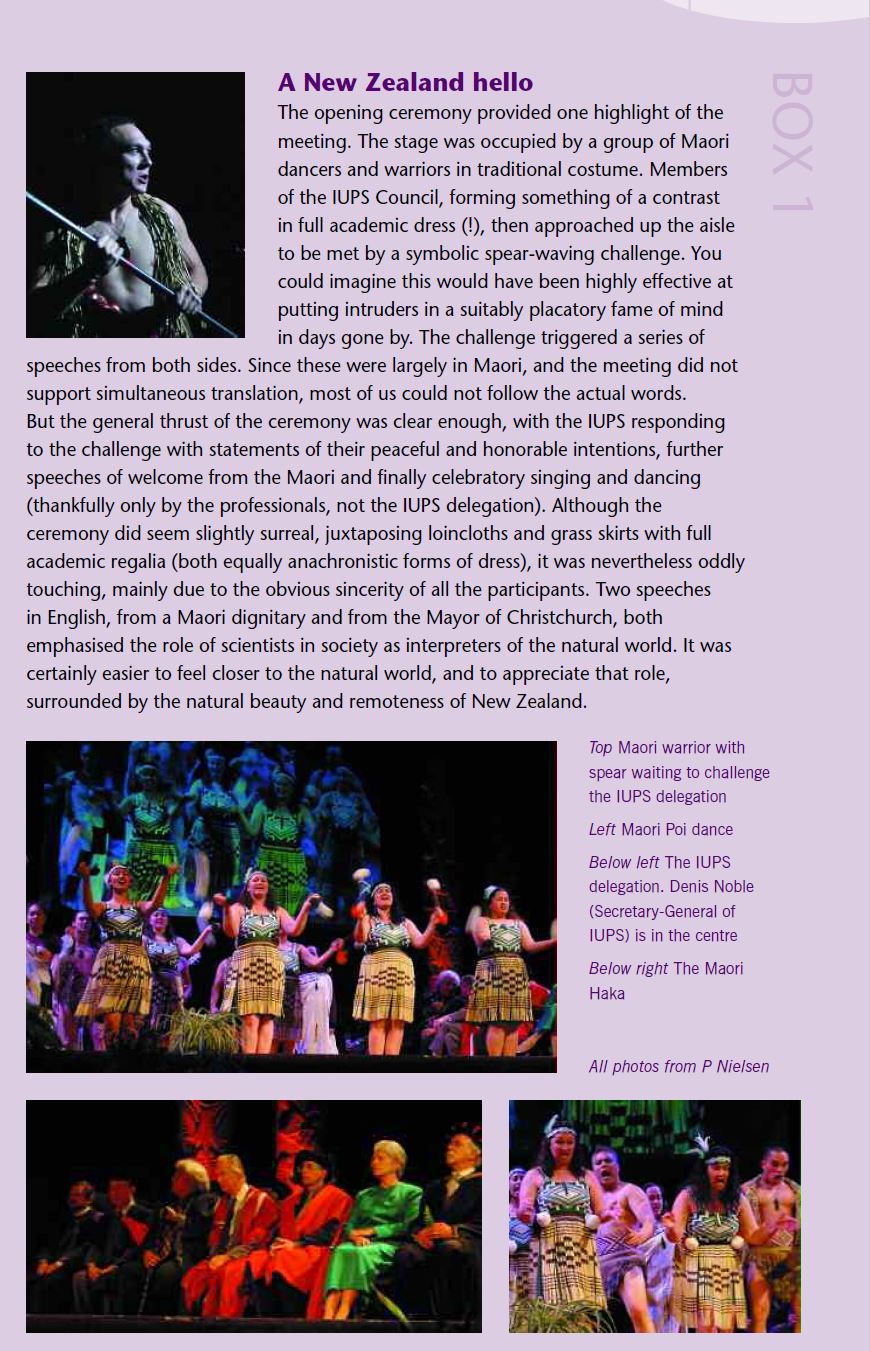

The conference formally started with the opening ceremony on Sunday afternoon (see Box 1), and by the time the meeting started in earnest on Monday morning we were ready. During the week we tried to assess how well the meeting achieved its evident desire to combine the two central subject areas in biology: physiology and pathology – or how organisms work and how they go wrong. Note that we don’t set much store by the current wave of hand- wringing about whether these subjects even exist any more (whatever the thoughts of people who reorganise university faculty titles). Ultimately, both physiology and pathology focus on functioning cells, or the “elementary patients” of medicine, to borrow a term from the excellent general pathology textbook by Majno and Joris. In spite of the ever-increasing focus by much of the biomedical research community on “molecular issues” over the last decade or so, there remains the basic biological truth that function is integrated at the cellular level. Consequently, it tends to be at this or the higher systems level that most biologically or medically relevant insights into normal or abnormal functioning are found. Whatever the current fads and fashions, that’s the way biology is. [That’s enough soapbox! – Editor.]

A conference style for the 21st century?

There were a number of interesting attempts to make the 2001 meeting “different”. First, there was no book of abstracts, just a programme booklet and a CD. A bank of 50 or so computers was available in the conference centre for delegates like us (Editor please note) not important enough to have our own laptop. Basically this was a laudable idea, but it didn’t quite work. A major flaw was the decision to include only major lectures, session titles and author names in the programme booklet. This made browsing the conference programme a pain, since you had to queue up for a computer to do it. Furthermore, the queues were often quite slow, because many delegates were using the conference PCs (at length!) to keep in touch with home by email. All that was required to have carried off the “paper-free abstract book” approach (conference organisers please note for next time) was a few extra pages in the booklet containing the actual titles of all the contributions. Then we could have browsed for interesting talks or have browsed for interesting talks or posters without waiting and without the added worry that our travel insurance didn’t seem to mention cover for spilling a double cappuccino over one of the conference computers.

Thesis, Antithesis Synthesium?

Another difference was the organisation of the bulk of the conference into “synthesia”. The idea was that each synthesium would contain three or four overview presentations in a general subject area, with time for discussion and debate. Many of the synthesia also had a related poster session. On the first day, for example, there were synthesia on “Data acquisition techniques for genome-based physiology”, “Water balance”, “Molecular motors”, “Ion channel gating”, “Modelling cellular complexity”, “Membrane targeting”, “Effects of mechanical forces on gene expression” and several others. Again, this was an excellent idea for a four-yearly overview meeting, though the variability of its success highlighted a number of operational issues. For these sessions to work well they need well- briefed speakers who stick to their remit, a proactive chairman who sets the scene, controls the speakers and stimulates debate, and adequate time for the debate to actually happen.

Successful sessions had the first two, but they could all have done with more of the third, namely time for discussion. Scientific meetings seem – like nature, politics and our in-trays – to abhor a vacuum, with organisers worried that too much time for discussion might lead to – horror of horrors – a session which finished early if the questions didn’t materialise. Hmmm, just think of the professional chaos that could cause. But it is surely better to risk having an extra cup of coffee than to hurry, or even cut off, a really interesting discussion that was just getting going. To get a flavour of a successful synthesium, see Box 2.

Keynotes, high notes, b*m notes?

Each day started and usually ended with one or more keynote lectures, which were again flagged as general overviews of the designated subject area. Some of these were excellent, but unfortunately, others were poor – and even sometimes downright dire – with several distinguished speakers obviously having made no effort to do anything other than wheel out their usual hyper-technical talk for aficionados. One such display was rewarded by half the audience walking out, and quite right too. It is surely a worrying sign of decadence in a profession when famous names – people who are supposed to set an example for the rest of us – seem willing to take the airfare, but unwilling to fulfil their remit, or even just to customise their standard talk slightly.

Incidentally, when we say that the day started with the keynote lectures, we are referring only to mere mortals. For delegates with Olympian constitutions (and specifically clinical interests) the organisers had thoughtfully arranged “Continuing Medical Education breakfast sessions” starting at 6.45 am (sic). Anecdotal evidence indicated that this format is North American in origin, raising the question – do American clinicians really enjoy getting up at 5 am? Rather nice coffee and croissants were provided, and for your correspondent who attended, the value of these sessions was only marginally impaired by his inability to think straight or focus his eyes properly, and an overwhelming tendency to assume a horizontal position within five minutes of the first slide.

Demonstrators and animal experimentation

One slightly unexpected feature of the conference was the presence on most days of a group of animal rights protesters outside the Town Hall and Convention Centre. Although they rarely numbered more than about a hundred, the demonstrators used drums to make as much noise as possible. The disruption to the meeting was actually fairly minimal, since the two main venues were linked by an enclosed bridge, meaning delegates didn’t have to walk through the protestors to get from one part of the meeting to the another. According to local sources, some fairly sensationalist pre-conference stories in the local media, particularly about American neuroscientist Michael Stryker, probably played a large part in generating the protests. After the publicity given to his experiments with the cat visual system, Stryker received at least one written death threat. Nonetheless, he courageously came to the meeting to give a Distinguished Lecture on his work, as well as defending his research in an interview on New Zealand National Radio.

Although the tone of the banners carried by the demonstrators was predictable (“They’ll get your pet”, “Cat-killing B*stards”, “Vivisection kills” and so on), little personal harassment or abuse was, to our knowledge, directed against individual delegates; indeed, compared to similar protests in Europe, it all seemed fairly low key. Most of the protesters were clearly young (teens or early twenties) and seemed content just with being there and being noisy. In general, there seemed to be a healthy measure of respect among many delegates for the demonstrators, or at least for the relatively restrained manner in which they made their protest. “It’s a democracy, so they have the right to be there” was one comment. “I think it’s a pity we’re not out there debating with them” was another.

The need to engage with the anti-animal-experiment groups, and with the general public, over the importance of animal experimentation was a recurring theme of the conference. The Mayor of Christchurch, Garry Moore, stressed the need for such dialogue in his opening speech, and this was reiterated again in the conference’s closing remarks. These events underlined the fact that, whatever past triumphs, all researchers need to be aware that the issue of the types and extent of animal research that society feels comfortable with is never going to go away. Everyone engaged in this type of work will continue to have to justify it and we can all play a part in ensuring reasoned and informed discussion. Having said that, a mature research community must also appreciate that there may be types of research which it feels are justified and reasonable, but which society at large does not support, even when well-informed of the rationale for the work.

From molecule to malady – or just halfway?

Another impression from the conference is the recurrent difficulty of convincingly bringing together non-clinical and clinical scientists. For a start, not many clinicians were there. And, with a few outstanding exceptions, it was particularly noticeable that hardly any of the presentations were by clinical scientists. Presumably this was at least in part because the meeting was mainly organised by, and for, basic scientists. But the upshot is that that the meeting was not totally successful in bridging the “molecule to malady” divide, because it did not include enough people who know in detail about the maladies. Of course, the converse also typically applies to meetings organised by clinicians. This problem is decades old, but it seems to have worsened noticeably in recent years as trends in the organisation and assessment of research, teaching and medical care have pushed the basic science and clinical communities further apart. But it remains important that we try harder to get round the problem, since improved dialogue along this axis can only be good for both groups.

New knowledge across the phyla

These problems aside, as a showcase of physiological science, the meeting was a success. Few delegates can have failed to learn something useful – even if it was something that they hadn’t realised they wanted to know! One of our favourites was a poster by the inimitable John West, which showed that elephants do not possess a pleural cavity (the parietal and visceral pleura are firmly stuck together). We are not entirely sure, though, about the explanation that this is because it prevents them from getting a pneumothorax when they wade across lakes and rivers with just their trunks above the surface (how much of a selective evolutionary pressure can that be?). Another gem was a presentation on elephant seals, pointing out that they should be classified as “surfacing mammals”, rather than diving ones, since they spend over 70% of their entire lives – and over 95% of their time at sea – holding their breath underwater. It is too early to tell whether studies like this will eventually help us understand the ways in which tissues can tolerate and even function normally under conditions of marginal oxygenation. But it is still amazing to think of these huge animals spending only 3 minutes per hour at the surface, for weeks on end, as they go about their daily business. After all, knowing about these things for their own sake and for the deeper appreciation of our world – curiosity-driven research – is a large part of what science is supposed to be about. The next IUPS congress is in 2005 in America and the one after that is in 2009 in Kyoto in Japan. See you there.