Physiology News Magazine

A career for the retired physiologist: ‘social’ scientist

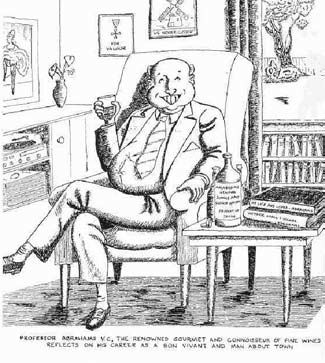

Vivian Abrahams extols the virtues of a part-time retirement career as a ‘social’ scientist

Features

A career for the retired physiologist: ‘social’ scientist

Vivian Abrahams extols the virtues of a part-time retirement career as a ‘social’ scientist

Features

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.54.33

Many hard-working physiologists find themselves pensioned off with 15 to 20 years of life ahead of them, and their senile dementia barely noticeable. Some deal with this situation by simply continuing to work at their previous job. As long as these older folks are productive, quiet and cost-free, or at least very cheap, employers with space to fill will be tolerant of their efforts. But even for these physiologists there comes a time when their labs will be closed voluntarily or involuntarily and the white coat finally hung up.

There are some retirees who find new congenial employment, perhaps running a B & B or working behind the counter at McDonalds.

Next there are those, dedicated physiologists to their last working day, who welcome retirement and walk out of their laboratories with a sigh of relief, relishing the new found freedom, peace and idleness. For these folks there is joy in their lives that there are no longer students to disturb the even tenor of the day, that the ever more intrusive demands of the granting agencies are irrelevant, that tedious experiments that go long into the night and still produce inconclusive results are a thing of the past, and that the demands of Department Heads and Deans can be ignored. If by chance the retiree was a Department Head or Dean, then they will be able to relish not having to contend with inadequate budgets and space as well as faculty, staff and students – all with unreasonable expectations and bad attitudes.

Lastly, there are also those individuals who have spent years planning for their retirement. They have attended all the available retirement planning seminars for the past 20 years. Their finances are in order, their wills written and their burial plots ordered and paid for. They have even ordered the seeds and plants for the garden that they will tend in the recently purchased retirement cottage located at the end of a peaceful lane in the countryside. For them, all those plans for their retirement can now be successfully fulfilled, even if it turns out that they hate living in the country.

At some stage most of these retirees will have some reason to visit the old Department. Perhaps to attend the retirement party of a colleague, to hand out a prize or to participate in the annual Xmas party. Now is the time when they come face to face with one of the realities of retirement. In the very institution in which they laboured for many years at an occupation which was the centre of their lives, they have become a non-person. Their laboratories have not vanished, but there are new names on the doors and the space is now occupied by strange equipment that has replaced old and treasured items. The office that for so long served as a private retreat has a new occupant, who is not known to you and who has rearranged the office so that it is no longer recognisable and has lost its former womb-like appeal. Technicians once deferential are no longer willing to give you anything but a friendly smile, and the treasured secretary who once fulfilled every wish (well, almost every wish) can only now manage raised eyebrows and a punctilious ‘hello’. Even the diligent computer technician is now too busy to help and, horror of horror, your name has been removed from the departmental directory board! Your public persona as a physiologist has disappeared. As far as the world of physiology is concerned you have entered the world of has-beens (or, worse still, the world of the never-was). As you digest the shock of this new state of affairs you realise that you are not yet ready to relinquish your old persona.

Welcome to your new part-time retirement career as a ‘social’ scientist! You now need retraining to become a new kind of physiologist with a new vocation appropriate to yourself as an older person, retraining that builds on those years of work, that takes from the past, benefits from all your accrued wisdom, and which fits someone with time on their hands and a serious history as a physiologist.

The physiologist as a ‘social’ scientist may be defined as someone whose role in science is no longer in teaching, research or administration, but consists in attendance at scientific meetings, attendance which is strongly, perhaps entirely, influenced by the social context of the meeting.

The criteria, in no particular order, may include: the physical location of the meeting; the relationship of that location to the domicile of friends, or to a favourite restaurant, to a museum, historic sites, discount mall, vineyard, art gallery or ski slopes or even a beach. There are other factors that enter into the decision of the ‘social’ scientist. Locations which enable the cold of winter to be mitigated or avoided can be of importance. Similarly, locations that permit a fuller enjoyment of the summer months are also important – and this might include opportunities for golf or horseback riding.

Retirement does not remove you from the great adventure of physiology. It merely changes you from being an active participant to an informed spectator.

Why, it might be argued, would you need to go to a scientific society meeting to enjoy any of these pursuits? If you need to ski, go to a ski resort. Shopping can be done at home, or perhaps even on horseback. This is true, but there is one really important thing that draws the social scientist to meetings, and it is inherent in the nature of a career in science. A career in science means being part of a shared adventure, an adventure shared with many people. Some of these are physically close, perhaps in the same department, but many of those that you have shared your career with will be located many miles away, often in other countries. Retirement does not remove you from the great adventure. Rather, it changes you from being an active participant to a spectator. Not just any spectator, but an informed one who knows many of the players and many of the problems that are being tackled and who is very interested in the new developments and new ways of thinking. A scientific meeting is no longer about you presenting your latest and newest findings. Instead it is a chance to hear about the work of other people and to do so in the company of friends and colleagues of 30 or more years. It is a time to remember with them old battles and turning points, of the times in a career when cruel decisions had to be made, of triumphs, and of disappointments and mistakes. Even perhaps to recall some indiscretions of youth. Equally important, meetings now can offer a special kind of joy, the joy of seeing a student that one has nurtured now recognised as an authority and playing a major role in science. Even more joy when that student recognises the old mentor, and takes a turn at the bar picking up the bill. It is a chance to meet again the old colleagues who did, and continue to do, work that is amazing. And yes, the science might include a stunningly good, easily understood review lecture that revives the excitement that only good science can bring, or a communication might be presented that, at last, sheds light on a problem that has puzzled you for years.

Practical tips for the newly fledged ‘social’ scientist ….

Being a serious ‘social’ scientist does require the acquisition of a new set of skills for life on the fringe of science. It is essential to be able to relate sensibly to those who are at the meeting for a more serious purpose. Poster displays are easy to handle. For those posters that are too complicated, poorly understood, or totally incomprehensible, a polite nod to the author in passing will suffice. When, as can happen, a poster discussion has been entered into that has gone beyond your zone of knowledge or has entered the zone of your intellectual rust, an exit may be more difficult to engineer. Perhaps honesty is the best policy in this case. Ignorance confessed, and the farewell ladled with suitable praise for the author’s remarkable ability (note: terms like genius are best avoided), an exit can be made. Whatever has happened, once eyebrows are raised it is time to move on.

….a warm lecture room is a particular hazard….