Physiology News Magazine

A week in the Zambian Bush

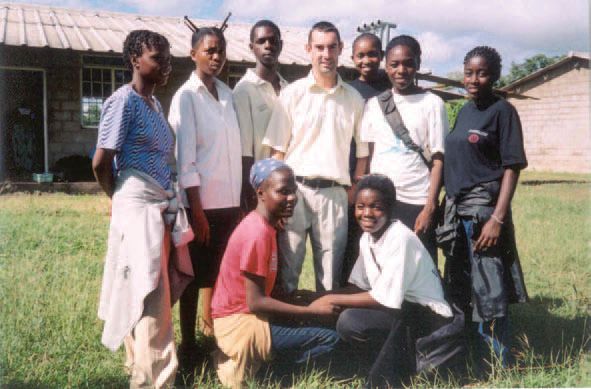

In May 2002, Physiological Society Member Tristan Pocock left the Physiology Department at the University of Bristol, where he was a senior post-doc researching the microcirculation, to spend 2 years as a VSO (*1) volunteer teaching high school biology in the Zambian bush

Features

A week in the Zambian Bush

In May 2002, Physiological Society Member Tristan Pocock left the Physiology Department at the University of Bristol, where he was a senior post-doc researching the microcirculation, to spend 2 years as a VSO (*1) volunteer teaching high school biology in the Zambian bush

Features

Tristan Pocock

Since this piece was written, Tris Pocock has returned to the UK and is now a Teaching Fellow in Pharmacology and Physiology at Manchester University

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.56.13

*1: Voluntary Services Overseas (VSO) is an international development charity, started in 1958 and currently has over 2,000 volunteers working in ‘developing countries’ worldwide.

A typical week begins with the Monday morning staff briefing. I usually emerge from under my mosquito net at 6.15am, having dozed since being awoken by chickens crowing at 4.00 (everyone in rural Zambia seems to own at least one chicken and they are usually let out well before dawn). The water is turned on at 5.30 in the morning for 30 minutes – if I want a wash, I have to jump in the cold bath for a few minutes and then refill it for washing clothes, plus filling bottles for drinking. Getting up this early was not part of my routine as a PhD student or postdoc! However, it is much easier to get up at such an unearthly hour with the sun streaming through the curtains 360 days a year.

Being better at getting up than my VSO housemate, Jenny, I make breakfast for us both (imported porridge oats), unless I am ‘Teacher on Duty’, in which case I am obliged to go to the dining hall to taste the ground maize porridge which the pupils get for breakfast. I leave the house for the 6.45 staff briefing, invariably arriving 2 minutes late. Other teachers arrive over the course of the next half an hour. With the staff suitably up-to-speed (or more likely confused) as to what lies in store for the week, we proceed to assembly. The best thing about assembly is listening to the very talented choir and joining in with the National Anthem (provided it’s sung in English, rather than the local language, Chinyanja). The worst thing is that it delays the start of teaching (often to the extent that the first lesson is lost entirely!). On other days of the week lessons start at 7.00 and go through until 12.40.

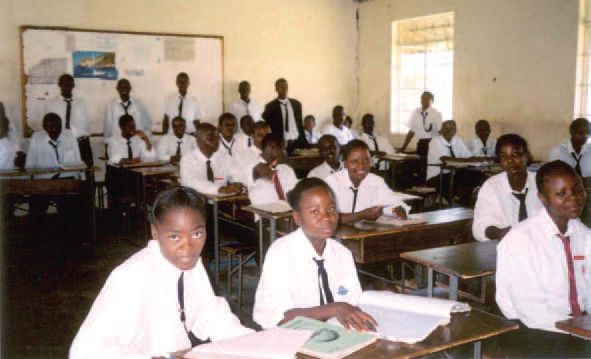

Before lessons, I take my class register. With 56 pupils in my class this often takes up all 10 minutes of registration. Lessons are generally 80 minutes in length, but seem to get longer and longer as the morning progresses and the temperature rises (in the hot season, it is 30oC at 7 am and often over 40oC by 12.40 pm!) Many pupils get up in the middle of lessons and lean against the wall. It took me a while to realise that this is to stop them from falling asleep!

I am the only biology teacher, but also teach chemistry sometimes. It was a bit of a shock having to dig deep into the memory banks for my long-neglected GCSE knowledge of atomic structure! Most of the higher education level biology I learnt is pretty irrelevant here. At the beginning I occasionally had to stop myself getting carried away and ranting on about growth factors when teaching blood vessel structure and function. In fact, it is the sometimes-derided ‘transferable skills’ from my time in higher education and research that are the most useful here – the ability to judge the appropriate level of explanation for the audience/class, to decide how detailed to make a diagram, and so on.

So how did I end up here? After nearly 10 years in research, I had the growing feeling that it was not a career for me in the long term, although I had no clear idea what to do instead. Having glimpsed different cultures around the world as a tourist, including South Africa, I knew I wanted to learn more. When I contacted VSO, they decided I was made to be a biology teacher! I do feel privileged to have received such a good education in the UK (honestly!), and VSO offered me a chance to use my knowledge to benefit others, as well as to live in a different culture for a couple of years. Having made the decision, I finished my contract, and then went, within the space of about a week, from the lab in Bristol to the bush.

I first arrived at the school after an arduous journey from the Zambian capital, Lusaka, where I had spent a few days acclimatising and learning about Zambian culture. From Lusaka I boarded the ‘chicken bus’ (so-called because of the ever-present chickens, and with hundreds of people crammed into every available space) for the long journey to Chipata, my ‘local’ town. After that, I endured a further 3 hour journey to the school along a heavily pot-holed dirt track, perched precariously on the back of a truck with all my worldly possessions and several nonchalant locals (with their luggage, bags of maize and, inevitably, more chickens).

My school, Mambwe High School, is a government-run mixed boarding school with almost 400 pupils, aged between 14 and 25. The pupils study in classes ranging in size from 22 to 60 (!) and sit exams similar to British GCSEs. The teachers (all Zambian except for Jenny and I) live on the school compound. The nearest post office, bank and supermarket are 87 km away in Chipata. Fortunately, the local BOMA (administrative centre), a mere 7 km down the road, has a few shops (which stock a wide range of biscuits and soap), a market (which sometimes has fresh vegetables) and even a bar (which, until electricity arrived in the District last year, served only warm beer!) There is a mission hospital 3 km away, which has one doctor (when he’s not called away to town) and several nurses, an X-ray machine and an operating theatre. My only experience of treatment there was when I got plastered after breaking my arm playing football.

I settled into teaching quickly – in contrast to my experiences of British schools (and universities!), the pupils are extremely respectful of teachers and were very willing to accept me. Unlike in the UK, secondary school teaching is a privilege many children here cannot afford. My experience as a physiology tutor at Bristol, and of presenting at national and international scientific meetings, helped me to come to terms with teaching – just as well, since my only previous experience at this level came from a week of shadowing teachers in a Gloucestershire secondary school. Learning the names of over 300 pupils was infinitely more difficult. All teaching is conducted in English, but it is not the first language (there are around 70 tribal languages in Zambia). Although pupils must pass an English exam at a fairly high level, for many their lack of English understanding is a major stumbling block to learning. Another hindrance is pupils being dragged out of lessons to draw water, collect firewood, mend the diesel generator (which powers the water pump and supplies lighting in the evening) or for punishment. Punishment usually involves an extended stint cutting the long grass on the school compound. This is useful because the long grass is where the

(malarial) mosquitoes breed. Cutting the grass is also an important part of impressing visiting dignitaries from the Education Ministry! Just as back in the UK, whistle-stop tours by the Great and the Good mean a frenzy to get things looking right, since visiting Big-wigs are rarely around long enough to do more than look.

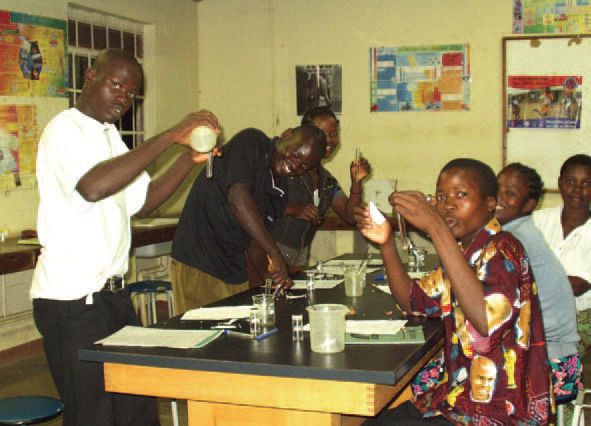

Back to the teaching. Due to the large class sizes, science practicals are a logistical nightmare. However, I decided to take the plunge and teach groups of 20-25 in the afternoons for practicals. The lab is surprisingly well-stocked for an African school – plenty of glassware and a cupboard full of chemicals, although most of them inappropriate for the level of teaching. Many of them are the kind of solvents you still find in UK university biology labs, but which were long ago banned from British schools for being too dangerous, like xylene and phenol. There are no COSHH regulations to worry about, though, and most of the pupils would be happy to dissect whatever wildlife they can get their hands on! Lack of running water and electricity is a hindrance, but not an insurmountable one – examples of practicals we do include testing the local produce for fats, proteins or carbohydrates, or comparing the features of local flora.

Morning tea break is a chance to re-energize with a cup of Zambian tea (more like a concentrated sugar solution with a hint of tea) and a scone. This probably saved me on a number of occasions from collapsing in the heat of the late morning! At 12.40, I return home for further vital rehydration and lunch (bread buns bought from a local village and sometimes tomato, followed by local bananas, all washed down with warm squash). Over lunch I play Scrabble with Jenny. This rapidly became an addiction, and we recorded over 150 games in one term!

Apart from the practicals, afternoons are spent marking, or on extracurricular activities, such as coaching the girls’ football team or meeting with the Anti-AIDS Club. AIDS is probably the major health issue facing the population here. The proportion of Zambians infected with HIV is around 25%, and about 1 million Zambian children have lost at least one parent to AIDS. Just on the laws of statistics, a significant proportion of my pupils must be HIV-positive. It is therefore very important that this generation of Zambian youth are active in instigating the behaviour changes necessary to reduce the infection rate. Fortunately, Mambwe High School has an enthusiastic Anti-AIDS Club. My involvement, as club ‘Patron’, is to facilitate discussion and to organise visits to other schools and villages. The pupils perform drama and poetry, sing and dance to raise awareness and educate other people about HIV/AIDS. The other Club I supervise is the Wildlife Conservation Club. The school is in a ‘Game Management Area’, so it is important for the pupils to understand that, while poaching is a way of life for many people here, conservation of rare species is imperative for maintaining the National Park (South Luangwa) as a popular tourist destination. This then provides income and employment for many local communities. The pupils know far more about the local wildlife than I do, and many are keen to work as guides when they finish school.

Typical early evening activities include badminton or tennis, on a specially constructed court in front of the house, followed by a cold bath (shared – but one at a time!) to coincide with the water being turned on, again for just 30 minutes. Dinner is a combination of tomatoes, onions (plus peppers if we can get them), and pasta or rice from the supermarket in Chipata. Dinner is followed by at least one game of Scrabble (by candlelight if the generator is not working), often interrupted by having to remove a gigantic insect or turf out noisy frogs. These latter might be Xenopus, although I couldn’t swear to it. I occasionally find myself wondering whether they have interesting muscle fibres, oocytes, or microcirculatory vessels, or whether I could ship them to the UK for experimental purposes.

If I’m feeling brave, I might venture up to school in the dark (no outdoor light except moon and stars here) to supervise evening ‘prep’, or do some marking before the power is switched off at 9.30 pm. After that, the compound is silent, except for the (often ear-piercing) sounds of cicadas and the occasional distant howl of a hyena or wild dog.

Weekends are usually spent at the school, preparing lessons, taking the Anti-AIDS Club on visits, watching the school football team play or relaxing. Perhaps the most unusual after-school activity so far was getting roped in to judge a pupils’ modelling contest! A downside of being on-site is that the pupils have no qualms about knocking on the door at 6 am on a Sunday morning to request a book. Lie-ins are a rare luxury given the intense heat during most of the year. Sometimes on Saturday nights I join the ‘drinkers’ on the 7 km excursion to the ‘local’ bar. If transport can’t be commandeered then we have to walk back in darkness, running the risk of meeting the odd hunting hyena en route – probably an insignificant risk, though, compared with walking back from a British pub after closing time! All in all, a far cry from my life in Bristol, where I had a choice of six pubs within 10 minutes walk from home. Weekends away start with hitching to Chipata on the back of a truck – a journey which can take anything from 1 to 6 hours, depending on the state of the pot-holed road, the recklessness of the driver and the degree of overloading.

Leaving research, after completing a Pharmacology degree, a PhD and then 4 years as a post-doc, to teach secondary school biology in Zambia was perhaps not the most obvious career move, but I have no regrets. Instead of being cooped up in a dark lab looking down a microscope at capillaries fluorescing (or not, on a bad day), I get to stand up in an open classroom in front of a large crowd of teenagers explaining how blood moves around the body. Like other teachers, I have more responsibilities concerned with the well-being of other people and hope that I have made a lasting impact on some of those I have met. If only one of my pupils decides to use condoms as a result of my attempts to explain how the HIV virus is transmitted, then several people might be spared infection with HIV. Aside from teaching, I’m sure I have learned as much from the people I have met in Zambia as they have from me. Every day has offered something new, and I have had some amazing adventures.

My experiences in Zambia have certainly changed my outlook on life. Teaching has been a refreshing change from the confines of a lab, and I am keen to continue teaching in some capacity when I return to the UK. Perhaps as a teaching fellow or demonstrator in a university department, or even as a secondary school teacher. Anyway, it has been great fun (if exhausting), and I would heartily recommend VSO to any young physiologist contemplating a career change from research to teaching.