Physiology News Magazine

Changing teaching practices of functional micro-anatomy in physiology

News and Views

Changing teaching practices of functional micro-anatomy in physiology

News and Views

Hugh Elder, David McEwan Jenkinson & David Russell

University of Glasgow, UK

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.95.10

In the last two decades in particular, a range of factors including financial constraints, technical and instrumental advances, and research strategies have combined to radically change the way that the teaching of histology and functional micro-anatomy is now conducted in universities. However, it is essential that invaluable teaching material is not lost as a consequence.

Many will still remember the time when every student had a class box of slides prepared to illustrate the structure of the major organs of the body and an individual microscope with which to examine them. Instruction was given by staff with an expansive knowledge of functional micro-anatomy and cytology, the correct use of the microscope (e.g. setting up Köhler illumination), the significance of the stain combinations used on the tissue sections, and ultimately the architecture and function of the organs at cellular level.

The histologist conducting the class usually first demonstrated the specific tissue and cellular characteristics by transparency projection or more recently by PowerPoint computer projection. Two of the authors well remember in Glasgow Physiology that, even for a decade after the Second World War, projection was accomplished by means of a horizontally mounted microscope; the intense light required was from a carbon arc between two sharpened carbon electrode rods, struck by a skilled technician.

Throughout the years, the conventional sectioning and staining techniques for optical microscopy have been greatly augmented by many technical advances such as confocal microscopy, fluorescence and phase contrast microscopy, enzyme and immuno-fluorescence techniques, GFP gene product tagging, and correlative strategies relating the optical level knowledge to electron microscopy.

In addition, computer software like PowerPoint and sophisticated scanning programs such as SlidePath or PathXL to record, display and disseminate images have expanded the options for histological instruction.

Influence of resource constraints

The resource demands to purchase and maintain microscopes of adequate quality and quantity, and to retain the trained histological technicians and service labs required to provide boxed slides for each student have presented an irresistible attraction to cash-strapped institutions, which have dispensed with them, especially when alternative and effective learning strategies are available. The advent of well illustrated texts together with provision of metadata and annotated computer displays has contributed to a steep decline in the number of trained conventional histologists in universities; only pockets remain in specialist institutes.

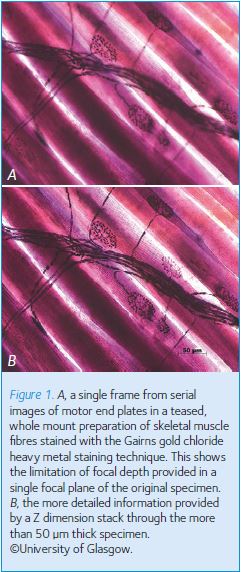

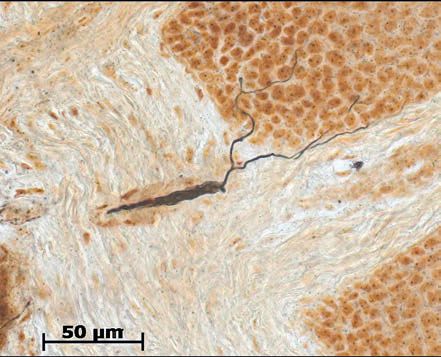

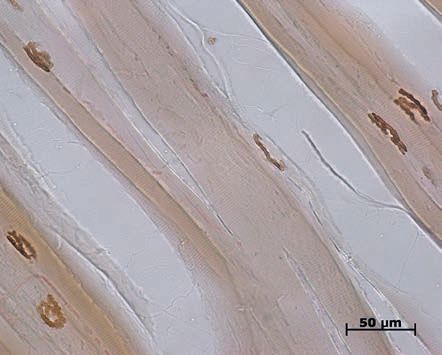

In Glasgow there are no longer any dedicated histologists, as opposed to pathologists, within the university, although we have a rare slide collection stretching back over the last hundred years. These are not simply ‘H & E’ stained sections but specimens that exhibit particularly clear specific features donated by successive generations of histologists as demonstration examples in their chosen field. The collection includes early material donated by HSD Garven, who learned heavy metal staining techniques for the nervous system during a period with Camillo Golgi in Italy and who with FW Gairns subsequently continued peripheral nerve work in Glasgow including the development of the gold chloride technique (Figs 1 and 2). Early enzymatic demonstration of the location of the hydrolytic enzyme responsible for the degradation of ACh in the endplate membranes (Fig. 3) supplements the anatomical information.

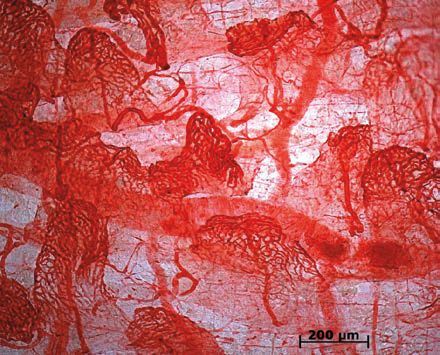

The collection also contains examples of the historical development of histology from early spread preparations and thick hand cut sections that predate reliable microtomy (Fig. 4). The collection has become scattered as departments have combined into schools and colleges and it is gradually deteriorating in storage. Its extent and content are no longer known and some of the accompanying metadata have been lost.

Digital archiving

However, although teaching methods have changed, an understanding of cellular structure and function is still an essential component in the training of clinical students and research biologists and the need for the best histological images remains.

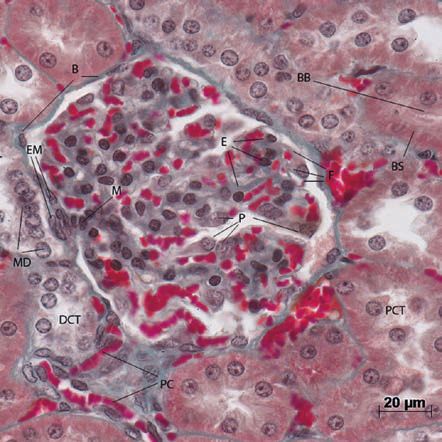

Hence, somewhat belatedly, in recent years we have embarked upon a core objective of digital archiving to ‘save’ the collection. Initially the best of the slides are being selected for scanning, using the SlidePath system, and we are adding available metadata. Sadly some 23% of the slides examined so far have deteriorated to the extent that they are no longer usable. A concomitant objective of making the images of the collection as widely accessible as possible to both staff and students for educational purposes is served by the addition of further annotation as time and resources permit. When particular cytological detail of the best quality is found it is being augmented with images taken at the limit of conventional optical resolution (~0.2 μm point to point resolution) with best quality oil immersion objectives (Fig. 5).

With the project now well advanced we hope shortly to encourage staff with personal collections to augment the collection and add to the basic labelling, thereby creating a really useful teaching resource as well as preserving the collection in a readily accessible, immediately useable digital archive. This annotation stage is undoubtedly the most time and effort consuming phase of the project and we are currently seeking further financial support to complete it.

Further phases are anticipated as we expand the project to the slide collections in the medical, veterinary, dental, biomedical and pathological disciplines to provide ultimately a centralised university teaching and research resource.