Physiology News Magazine

Charles Bell’s ‘sixth sense’

His deductions on movement and position sense

Features

Charles Bell’s ‘sixth sense’

His deductions on movement and position sense

Features

Jonathan Cole

Poole Hospital and University of Bournemouth, UK

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.110.32

The discovery of rare human subjects with absences of discriminatory touch and proprioception, either acquired or from birth, has allowed insights into the role of these senses in the control of movement and other functions. Many of these were anticipated in the 1820s by the remarkable, largely theoretical, work of the Scottish physiologist and anatomist, Sir Charles Bell.

It is rare for clinical neurological syndromes to overlap exactly onto neurophysiological classifications, but this does occur in the acquired, acute sensory neuronopathy with a selective loss of large myelinated sensory nerves, leading to the complete loss of touch and movement/position sense in the body (Cole, 1991). More recently, patients have also emerged with a selective loss of discriminative touch and profoundly decreased proprioception due to an inherited inactivating variant in the stretch-gated ion channel PIEZO2 (Chesler et al., 2016). Many of the problems these participants face were anticipated in one of the first descriptions of proprioception in the early 19th century by Charles Bell.

When King William IV, in 1831, was looking for eminent scientists to knight, alongside the usual politicians and military men, Bell was an obvious choice. (Hershel and Babbage were two of the other six, though the latter declined the honour).

He was born in 1774 in Edinburgh, and trained there in medicine before moving to London in 1804. Initially, he taught anatomy and assisted at operations. He must have been good since he became Professor of Anatomy at the Royal College of Surgeons, the first Professor of Surgery at UCL and helped found The Middlesex Hospital Medical School. He was a fine artist too, and at one time hoped for a chair at the Royal Academy of Arts. His book on facial expression, written and illustrated by him, influenced artists in Britain and abroad, including the pre-Raphaelites, Gericault and Delacroix. In the aftermath of Waterloo, he travelled to Brussels to assist in surgery, and subsequently wrote and – naturally – illustrated a book on gunshot wounds.

His main area of expertise, and the reason he is remembered today, was the function and diseases of the nerves and brain. His name is most closely associated with Bell’s Palsy (inflammatory facial palsy), and with Bell’s phenomenon (upward rotation of the eye as the lid closes). He described forms of muscular dystrophy, writer’s cramp and motor neurone disease as well as phantom limb sensation (and how these absent limbs may be felt to move with gesture) and how the arch of the foot acts as a spring during propulsion. He was elected to the Royal Society in 1826 and was later awarded its Gold Medal. Commenting on his knighthood, The Lancet effused, ‘There is not in England an anatomist or physiologist toward whom the favour of the sovereign could have been bestowed with more propriety.’

In addition to his anatomy and neurology, he also made key physiological observations. Bell described how the different senses arise in the brain rather than being due to different properties of sensory afferent nerves, before Muller’s formal doctrine of specific nerve energies. He gained experimental evidence for reciprocal inhibition and realised that some integrative functions occurred in the spinal cord. He wondered if babies feel pain, ‘He is capable of the expression of pain… but the infant during operations makes no effort to repel the instrument of surgeon when being operated on.’ He also suggested that, ‘For the nervous system it holds universally that variety of contrast is necessary for sensation, the finest organ of sense losing its property by the continuance of the same impression.’ At other times his ideas, based on inadequate data, were wrong; for example, he thought the cerebellum was an autonomic centre.

In his thorough and scrupulously fair recent biography (Aminoff, 2017), Michael Aminoff calls him an anatomist and theoretician. This seems reasonable, in part because of his attitude to experimentation. This required vivisection without anaesthetic (as surgery was then also performed). He distrusted results under such circumstances and thought it distasteful;

‘I should be writing a third paper on the nerves, but I cannot proceed without making some experiments, which are so unpleasant … that I defer them – I cannot convince myself that I am authorised in nature, or religion, to do these cruelties – for what? – for anything else than a little egotism and self-aggrandisement’ (Gordon-Taylor & Walls, 1958).

Despite his worldly success and his many, acclaimed, contributions, Bell was easily aggrieved, resigning from many of the posts to which he was appointed. There were also controversies from which he emerges poorly. In 1811, during an experiment, he had shown that touching an animal’s ventral root led to convulsion while cutting the dorsal ones did not. His interpretation was that dorsal roots project to cerebellum; crucially he did not write this up adequately. In 1822, Magendie cut dorsal and ventral roots in young puppies, allowed them to recover and observed the consequences, and concluded correctly that ventral roots were motor and dorsal ones sensory, completely independently of the previous work. Bell was indignant and, Aminoff suggests, revised his own writings to imply that he made the correct deduction himself earlier. Around the same time, he also altered his papers on the sensory and motor innervation of the face, by the Vth and VIIth cranial nerves, following correct observations by the British anatomist Herbert Mayo. Much acrimony over many years followed and the episodes bring Bell no credit.

Beyond this, however, one of his major physiological contributions was his description of the ‘sixth sense’, muscle sense, in a paper to the Royal Society in 1826,

‘weighing in the hand – what is this but estimating muscle force? We are sensible of the most minute changes of muscular exertion, we know the position of the body and limbs. In standing, walking and running, every effort of the voluntary power which gives motion to the body, is directed by a sense of the condition of the muscles.’

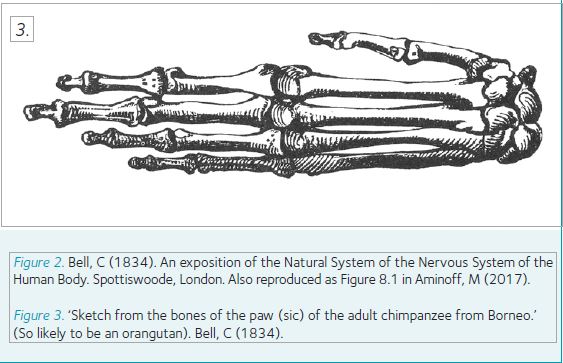

Many of his conclusions about what Sherrington subsequently termed proprioception are within his book, The Hand, which was one of the Bridgewater Lecture series published in 1833 (Bell, 1834). These were designed to defend Christianity from the then current scientific advances. Bell was religious and a supporter of creationism and intelligent design, neither of which impressed Darwin. Though the books were meant to convey ‘safe science’ and religion to the everyman, Bell sneaked in some astonishingly, prescient ideas which followed one of his original experimental observations;

‘muscles had two classes of nerves – on exciting one the muscle contracted; on exciting the other, no action …

Thus, it was proved that there is a nervous circle connecting the muscles with the brain … there is a muscle of sensibility to convey a sensation of the condition of the muscles to the sensorium, as well as conveying the mandate of the will to the muscles.’

From here he concluded;

‘We awake with a knowledge of the position of our limbs. This cannot be from a recollection of the action which placed them where they are; it must, therefore, be a consciousness of their present condition.’

Much of my own research has been in participants with touch and proprioceptive loss, and many of Bell’s insights are directly applicable. For instance, these participants on wakening actually do move their limbs to see where they are in bed.

‘In truth we stand by so fine an exercise of this power, and the muscles are, from habit, directed with so much precision and with an effort so slight, that we do not know how we stand. But if we attempt to walk on a narrow ledge, or stand in a situation where we are in danger of falling we become subject to apprehension; the actions of the muscles are magnified and demonstrative to the degree in which they are excited.’

Here he suggests that though describing them as a ‘sense’, proprioception and intention lie between the conscious and

the automatic. Even similar actions can be either, according to context, his example being walking across a narrow ledge. The choreographers Siobhan Davies and Matthias Sperling recently developed a piece, ‘Manual’, in which they asked members of the audience to instruct a dancer how to stand from lying. We do this easily, without thought, but it is extraordinarily difficult to analyse exactly what we do and to put that in words to instruct someone else.

‘Nothing appears simpler to us than raising an arm … yet in that single act, not only are innumerable muscles put into activity, but as many are thrown out of action, under the same act of volition.’

Here he describes reciprocal action and the complexities of even a simple action. In the next passage he considers what we now know as active touch, ‘… in the use of the hand there is a double sense exercised; we must not only feel the contact of the object, but we must be sensible to the muscular effort which is made to reach it, or to grasp it with the fingers … Without a sense of muscular action or consciousness of the degree of effort made, the proper sense of touch could hardly be an inlet to knowledge at all … the motion of the hand and fingers, and the sense or consciousness of their action must be combined with the sense of touch …’

‘The motion of the fingers is especially necessary to the sense of touch. These bend, extend, or expand, moving in all directions like palpa, embracing the object and feeling it on all surfaces, sensible to its solidity’

He even considered whether this sixth sense was all due to peripheral feedback or whether to internal efferent signals,

‘At one time I entertained a doubt whether this proceeded from a knowledge of the condition of the muscles or from a consciousness of the degree of effort directed to them in volition’

Lastly, he mused on what might be called affective or pleasurable aspects of proprioception, to parallel pleasant touch,

‘The exercise of the muscular frame is the source of some of our chief enjoyments. This activity is followed by weariness and a desire for rest … diffused through every part of the frame a feeling almost voluptuous.’

Bell was a founder of neurology and neuroscience, and a pre-eminent medical figure of his time, so it is curious how readily he took offence. He resigned from UCL for not being given the Senior Chair of Anatomy and even baulked at the Chair of Physiology, protesting that he had not lost interest in ‘practical subjects’, and demanded the Chair of Surgery or Clinical Surgery as well. Having a thin skin is less reprehensible than his responses to the dorsal and ventral root and the cranial nerve controversies. One simple lesson is to write up experimental results and publish in a widely read journal.

His behaviour, however, should not blind us to his huge contributions to clinical neurology and to his insights into proprioception and the consequences of its loss. Bell lived at the dawning of empirical physiology and one presumes would have embraced experimentation under more humane conditions. His observations and subsequent theories and deductions remind us that ideas are often not a new as we may think; the importance is in their experimental verification. His life also reminds us that even a scientist of extraordinary gifts can have flaws.

References

Aminoff M (2017). Sir Charles Bell. Oxford, New York: OUP.

Bell C. Sir. (1834). The Hand; Its Mechanism and Vital Endowments, as Evincing Design. London: W. Pickering. Reprinted 1979, Brentwood: The Pilgrim’s Press.

Chesler AT et al. (2016). The role of PIEZO2 in human mechanosensation. N Engl J Med 375, 1355–1364. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602812.

Cole J (1991). Pride and a Daily Marathon, London; Duckworth, 1995 Cambridge, MA: MIT Press and (2016). Losing Touch. Oxford: OUP.

Gordon-Taylor G & Walls EW (1958). Sir Charles Bell: His Life and Times. Edinburgh, London: E & S Livingstone.