Physiology News Magazine

Crossing the pond for your academic career:

Is the leap worth it?

Features

Crossing the pond for your academic career:

Is the leap worth it?

Features

Havovi Chichger, Department of Biomedical and Forensic Sciences, Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge, UK

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.112.24

On 14–16 September 2018, a myriad of physiology researchers will descend on QEII centre in London for Europhysiology 2018. Conferences such as these allow the research community to network and collaborate on everything from the development of novel concepts to the sharing of technical expertise. Physiologists from around Europe and far further afield attend, bringing with them a range of diverse research ideas, academic cultures and backgrounds. In 2011, I moved to the USA for my postdoctoral fellowship, and I returned to the UK in 2015 with more experience and a wider perspective on academic research. As the conference nears, I have been reflecting on my own experience of the differences between academic research conducted in different countries and how it has shaped my career, highlighting how truly mobile you can be with your academic career.

What mobility in science meant for me

Scientific research, like so many other sectors, undoubtedly benefits from an international community. I would struggle to name a research group, my own included, which does not include researchers with a range of nationalities from across Europe and around the world. This is never more obvious than during ‘potluck’ lunches where we all enjoy a wide variety of delicacies from around the world. But exotic food aside, what does this diversity mean for the research community?

As a PhD student at University College London (UCL), I was part of a brilliant but relatively small laboratory at the Royal Free Hospital, with only one other PhD student and a postdoctoral fellow. I primarily worked on models relating to diabetes and metabolic disruption and studied the physiology of glucose transporters in the renal epithelium (Chichger et al., 2016); my work was awarded the young author prize in 2016. Nearing the end of my PhD, I realised that I had significant experience in renal physiology and was keen to broaden my research skills, particularly with regards to studying the signalling mechanisms which regulate glucose transporters and epithelial barrier function at a cell and molecular level. Throughout my undergraduate and postgraduate studies, I had encountered many ‘success’ stories from supervisors, colleagues and collaborators about researchers who moved to US academic laboratories to further develop their expertise.

There are a slew of leading UK physiology researchers who have spent large segments of their career in overseas laboratories, particularly in the USA. With statistics in the UK indicating that only 3.5% of PhD graduates progress to positions as permanent research staff, and only 0.45% become professors (of which a mere 20% are female), I decided that any opportunity to strengthen my career had to be a good thing (Royal Society, 2014). I was happy to expand the scope of my research but I wanted to stay within the field so I applied for postdoctoral positions in physiology laboratories performing translational science on epithelial and endothelial barriers. Within weeks I found myself doing phone interviews and getting offers from a range of universities. A hop, skip and a viva later, I found myself in Providence, Rhode Island, starting a postdoctorate with Elizabeth Harrington at Brown University who recruited me on a 2-year contract to work on a National Institute of Health (NIH) grant studying cell signalling in the pulmonary endothelium in acute respiratory distress syndrome.

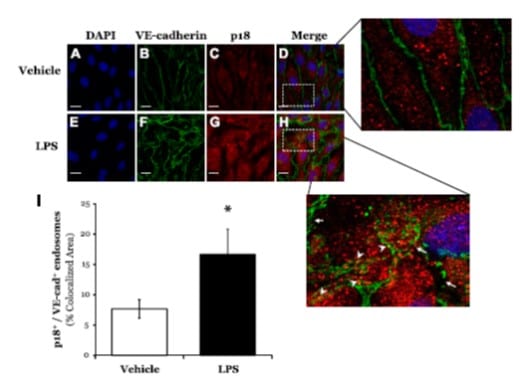

Figure 1. The first published experiments from my independent American Heart Association grant identifying the presence of p18/LAMTOR1 in the lung microvasculature. Studies such as these allowed me to develop my experience with cell signalling mechanisms whilst staying in the physiology field. Immunofluorescence studies show that LPS increases co-localisation of p18/LAMTOR1 with VE-cadherin positive endosomes (Figure adapted from Chichger, 2015).

Figure 1. The first published experiments from my independent American Heart Association grant identifying the presence of p18/LAMTOR1 in the lung microvasculature. Studies such as these allowed me to develop my experience with cell signalling mechanisms whilst staying in the physiology field. Immunofluorescence studies show that LPS increases co-localisation of p18/LAMTOR1 with VE-cadherin positive endosomes (Figure adapted from Chichger, 2015).And then the fun started…

My first year at Brown University was a steep learning curve. I was working in a large laboratory with around eight technicians, four postdocs and five principal investigators. The pace of work was high, with a continuous push for publishing and working towards preliminary data required for grant submissions. The expectations of me as a postdoctoral researcher were high – because of the academic system, my peers in USA had all spent 5–6 years on their PhD, attending a variety of classes, being a teaching assistant and developing experience which I had simply not had time to achieve in my 3-year PhD. Working within such a high-paced team, with investigators all focused on pulmonary diseases, I had the opportunity to learn a wide range of technical skills using state-of-the-art equipment and disease models, like the electric cell impedance system (Chichger et al., 2012) and pulmonary hypertension (Chichger et al., 2014). Then there were the networks in the respiratory disease field which I had access to, opportunities to collaborate and connect with specialists in the field, and to present at conferences. o be clear, these opportunities are undoubtedly available in the UK, but only a small proportion of my peers who were early stage postdocs across the Atlantic were given these chances. In my experience, this was largely due to the higher expectations of a US postdoc, given the longer time to complete a PhD. After my first year, two papers and one published book chapter later, I was encouraged to apply for a postdoctoral fellowship award. As a UK citizen, with a J1 visa, I had limited options for where to submit an application with strict eligibility criteria from the major US funders. I developed an independent research project plan to study the role of a novel endosomal protein, p18/LAMTOR1, on vascular permeability in acute respiratory distress syndrome (Chichger et al., 2015a; Chichger et al., 2015b).

After three applications, I was awarded a two-year fellowship from American Heart Association to study p18/LAMTOR1. From this point onwards, I had greater freedom than I had ever experienced in my research. I had my mentoring team for support but suddenly I was independently developing my research, managing a budget, spearheading my papers and asked to review papers. Again, a luxury, which the majority of my UK peers may not encounter at my career level. So far, so good.

Table 1. What I wish I had known.

| Funding

Career progression |

Be aware of your visa restrictions – many traditional US funders (e.g. National Institute of Health and National Science Foundation) have limitations on postdoctoral grants so ensure you check the small print before spending time preparing an application. Think outside the box for funders; for example, there are several foundations which are particularly supportive of overseas applicants (e.g. Human Frontiers Science Program).

Mobility in science typically means joining different research communities and societies, expanding your mentor network, and having the opportunity to experience a range of different conferences. Whilst these are undoubtedly great advantages, it is important to remain a member of a UK society and keep abreast of the current research climate. This will allow you to keep an eye on the job market if you are looking to return to the UK. |

Before you start packing your suitcase

Of course, this works just great when the economic and political landscape remains stable. There may be many that feel the events of 23 June 2016 (Brexit) have abolished this mobility in science. Many schematics of the future of UK research are dependent on a careful balance between the decisions made regarding UK migration policy and our access to international funding and infrastructure (Royal Society, 2017). This has, and will, undoubtedly play a role in how freely scientists can move; however, there are also other pressures facing scientists, which differ greatly from those in the US, such as the REF (Research Excellence Framework) which assesses the quality of research in UK universities, and the resulting emphasis on research impact, as opposed to just high-impact papers.

Another consideration is the logistics of packing up and shipping to a different country. For me, this involved endless trips to the US embassy in London, saying goodbye to all my loved ones, learning to do the US dollar to UK pound conversion in my head, and learning to drive on the other side of the road. This was definitely part of the adventure, but if I had not loved the research and the laboratory I was working in, the adventure would have gotten old very quickly.

Would I do it again? Yes, in a heartbeat. Whilst there are some pointers which I would have liked to know ahead of time (Table 1), I am perpetually encouraging my PhD students and mentees to consider moving to a different country for a postdoctorate. There are the obvious advantages such as learning different techniques and skills; however, this does not typically require a new visa. For me, this mobility gives you a different perspective on research and lends opportunities to experience a different academic system, apply for different funding, attend different conferences, and network with different researchers, and it is these experiences, which I believe, make us more resilient and open-minded researchers and therefore shape our approach to our field of research.

References

Chichger H, Braza J, Duong H, Stark M, Harrington EO (2015a). Neovascularization in the pulmonary endothelium is regulated by the endosome: Rab4-mediated trafficking and p18-dependent signaling. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 309(7), L700–709.

Chichger H, Cleasby ME, Srai SK, Unwin RJ, Debnam ES, Marks J (2016). Experimental type II diabetes and related models of impaired glucose metabolism differentially regulate glucose transporters at the proximal tubule brush border membrane.

Exp Physiol 101(6), 731–734.

Chichger H, Duong H, Braza J, Harrington EO (2015b). p18, a novel adaptor protein, regulates pulmonary endothelial barrier function via enhanced endocytic recycling of VE-cadherin. FASEB J 29(3), 868–881.

Chichger H, Grinnell KL, Casserly B, Chung CS, Braza J, Lomas-Neira J, Ayala A, Rounds S, Klinger JR, Harrington EO (2012). Genetic disruption of protein kinase Cδ reduces endotoxin-induced lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 303(10), L880–888.

Chichger H, Vang A, O’Connell KA, Zhang P, Mende U, Harrington EO, Choudhary G. PKC δ and βII regulate angiotensin II-mediated fibrosis through p38: a mechanism of RV fibrosis in pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 308(8), L827–836.

Royal Society (2014). Future protecting report.

Royal Society (2017). Research and Innovation Futures after Brexit: Scenarios.