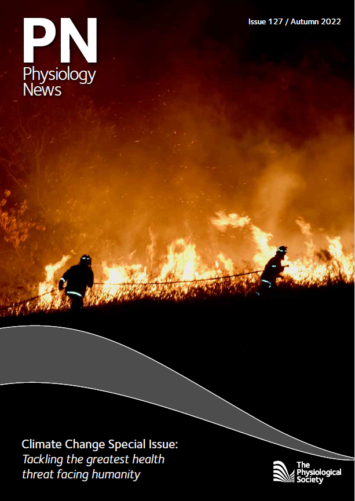

Physiology News Magazine

Editorial

The perils of climate change: How physiology can save lives in our changing world

News and Views

Editorial

The perils of climate change: How physiology can save lives in our changing world

News and Views

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.127.5

Dr Keith Siew

Scientific Editor, Physiology News

If you go to your medicine cabinet, fish out your old school glass thermometer and wrap the mercury reservoir of that thermometer in damp cotton… Then congratulations… You have just created a terrifyingly simple model of human thermoregulation, a device capable of measuring the “wet-bulb temperature”. Something you can expect to hear more of in the coming years.

The concept is straightforward. When humidity is low, the wet-bulb’s temperature remains lower than that of the ambient air through the shedding of heat by evaporation; similar to that of sweat evaporating from our skin. However, as humidity is rising (and no, the barometer is not getting low… before you go getting any ideas) the ability to shed heat reduces and eventually at 100% relative humidity the air becomes saturated with water vapour and the wet-bulb temperature will match that of the ambient air. This is the scary point at which no amount of sweating will cool you down.

Even for a young fit healthy individual a wetbulb temperature of 32°C would render them unable to carry out most normal outdoor activities. At only a few degrees higher we hit the theoretical survivability threshold of 35°C, where even with an endless supply of water and stripped to bare skin, one cannot survive more than a handful of hours at best. Originally climate models had projected the first occurrences of wet-bulb 35°C to emerge by the mid-21st century, but a close inspection of weather station data shows that several places on the planet have already hit this, albeit for brief moments in relatively unpopulated areas. However, extreme heat can put enormous stress on the cardiovascular system and even wet-bulb temperatures of 28°C have resulted in large amounts of excess deaths, for example in the 2003 European and 2010 Russian heatwaves.

And despite all this going on, it seems many have their heads buried in the sand. I don’t know about you, but I’m certainly not appreciating the alarming frequency at which “life imitating art” is playing out in recent years (and unfortunately not the fun movies with happy endings). At first it was 2011’s Contagion, which seemed another starstudded blockbuster with a far-fetched and surreal doomsday event, but upon a recent rewatch (yes, I’m a glutton for punishment) it was eerily prophetic of our own impending pandemic. The all-too-familiar lingo of social distancing, R0 values, political miscalculations and snake oil promises rang through with a stark emotional tone, which I had (unsurprisingly) not felt on my first watch.

A decade later, our screens were graced with Don’t Look Up, a satirical and at times ridiculous post-Trumpian take on how we might respond to a ball of ice and rock on the apocalyptic scale, hurtling towards Earth. From this love-it-or-hate-it flick, one scene remains emblazoned on my mind, wherein the scientists breaking the news of our impending doom to the world are interviewed by news anchors insistent on putting a comic and positive spin on things. Twice now this exact scene has played out on British TV, except in this case the scientists aren’t astrophysicists but meteorologists and climate scientists. I couldn’t believe my eyes and ears; here was a meteorologist anticipating, many many excess deaths occurring as the UK soared to temperatures of 40°C, while the reporter berated him for being all doom and gloom, when she just wanted some good news and to feel good about the weather!

So, in response to this, we have chosen to focus this special issue on climate change and the role physiology has to play in our response to it. This includes a piece by Professor Hugh Montgomery who expertly lays out the path before us if we don’t change course, as well as a swathe of other articles covering recommendations from Professor Ollie Jay on how fan-based cooling may be beneficial or harmful, to an argument for the intertwined nature of air pollution and climate change by Dr Michael Koehle, and how taking advantage of our routes to school and work as an opportunity for physical activity could help combat climate change by Dr Julia Zakrzewski-Fruer. Lastly, we have contributions from Dr Ana Bonell on the disproportionate impact of heat stress on women during pregnancy in subsistence farming communities, a striking piece on the professional versus personal contributions of scientists to climate change by Martin Farley, and a piece by Professor Mike Tipton and Dr Gemma Milligan on how physiology may be well suited to come to the rescue.

We hope that this issue will impress upon all our readers the challenges and serious perils that await us without swift meaningful action, but also to give you some hope that many lives can yet be saved, and that physiology can provide some means to assist our adaptation to our changing world and mitigate the damage.