Physiology News Magazine

Florence Buchanan: A true pioneer

Membership

Florence Buchanan: A true pioneer

Membership

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.127.46

Professor Dame Frances Ashcroft

Department of Physiology, Anatomy and Genetics, University of Oxford, UK

Florence Buchanan is the first woman known to have attended a Physiological Society meeting and the first to be elected to The Physiological Society. Despite this distinction we know very little about her or what she looked like.

She was born in 1867 into a distinguished medical family. Her father, Sir George Buchanan FRS, became the Chief Medical Officer of the UK and is commemorated by a Royal Society medal (the Buchanan medal, which he endowed). She had five siblings, and her younger brother, Sir George Seaton Buchanan, also became a physician (Royal College of Physicians).

Florence read zoology at University College London, graduating in 1890, having published two papers as an undergraduate (something many of our current students would be extremely happy to do). These papers were on the respiratory organs of decapod crustacea and on annelids. She then studied marine polychaete worms with Ray Lankaster, discovering several new species (Buchanan, 1893; 1894).

In 1894 she moved to Oxford to work in the recently established Laboratory of Physiology, as a research assistant with John Burdon Sanderson, the Head of Department. She published several papers on the electrical responses of muscle (Buchanan, 1901), and in 1896 became the first women to attend a Physiological Society meeting. Burdon Sanderson resigned in 1904 when he was 76 – fortunately there was no enforced retirement age at Oxford in those days. Florence then moved to the Oxford University Museum of Natural History, where she set up her own lab. She was given the use of some equipment and she covered her research expenses with grants from the Royal Society.

She was especially interested in the frequency of the heart rate, and how it varied in different species, in hibernating animals and during exercise; for example, she measured the heart rate in awake and hibernating dormice. She also studied the form of the electrocardiogram (ECG), and transmission of reflex impulses in mammals, birds, and reptiles.

In addition to her many independent contributions (Buchanan, 1909; 1912), Florence provided data for August Krogh, who wrote “Miss Buchanan has shown us the very great kindness to take some electrocardiograms on subjects starting work on a stationary tricycle”. One of her subjects was the famous Oxford respiratory physiologist CG Douglas, who apparently was “not at all heated” by the exercise. It’s interesting that despite providing data for the paper (Krogh and Linhard, 1913), Florence does not appear as an author. Although we might hope this would be less likely to happen now, an article published in Nature this year shows that women in research teams are still systematically less likely to be credited with authorship than men – this applies at all career stages and across all research fields (Ross et al., 2022).

It can’t have been easy for Florence as not all men were happy with ladies in the lab. The physicist Henry Mosley wrote to his sister in 1909, “I got the Junior Scientific Society to ask Miss Buchanan to read them a paper on heart beats. Apparently Hartley for reasons known only to himself objected and tried to induce Balliol men to stir up dissension. They were to pretend that the presence of a lady in the club was illegal and as she had agreed to read before the fuss began it appeared things would become very awkward” (Helibron, 1974). Happily, the Balliol men didn’t oblige and the fuss fizzled out.

Whether Florence was aware of all this is unclear. But she would certainly have been aware of the shenanigans at The Physiological Society. The Physiological Society was founded in 1876 as a dining club “for the mutual benefit and protection of physiologists” in response to a Royal Commission of Enquiry into Vivisection. Meetings consisted of scientific presentations, followed by a dinner, and although women could attend the scientific part of meeting, they were excluded both from the dinner and (although not formally stated) from membership.

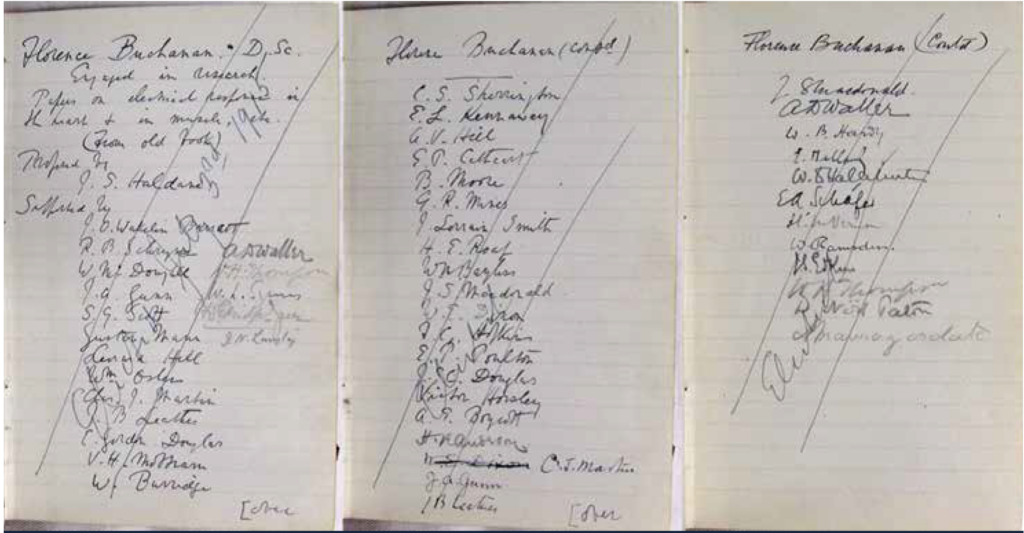

In 1912, after she had been going to The Physiological Society meetings for 16 years, Haldane proposed Florence for membership. His proposal in the Candidates Book stated she had a DSc, was engaged in research and had papers on “electrical responses in heart and in muscle”. She received 50 signatures of support and they make interesting reading. Haldane proposed her and supporting signatures came from William Osler, considered the father of modern medicine and Regius Professor at Oxford; CG Douglas, one of her subjects; Charles Sherrington, Nobel Prize winner and Waynflete Professor of Physiology; AV Hill; and also August Waller, who recorded the first ECG. The next step was for the names to be approved by a Committee before they were put to a membership ballot. But something clearly went wrong at this stage, because Florence’s name does not appear in the list of names put before the membership (Burgess, 2015).

Haldane again took charge and proposed that “it is desirable that women should be regarded as eligible for membership of the society”. The motion was passed at the AGM in January 1913. But the idea generated significant opposition, most famously from Ernst Starling, of Starling’s law of the heart fame, who argued that it “would be improper to dine with ladies smelling of dog – the men smelling of dog that is” (Evans,1964; Tansey, 1993). Fortunately, however, a membership ballot in June 1914 resulted in overwhelming support for women: 94 members voted to admit women on the same terms as men, 36 to admit them as Associate Members and 31 voted to leave the rules unchanged (Burgess, 2015). And so it was that at a Committee meeting in Oxford on 3 July 1915, with Sherrington in the Chair, the first six women were elected, with Florence heading the list of them.

Florence was probably instrumental in this change as she was not only the first women to be proposed, but she had given at least 10 communications to The Physiological Society, published two papers in The Journal of Physiology and three in the quarterly Journal of Experimental Physiology (now known as Experimental Physiology). Indeed, her paper on the time taken for the transmission of reflex impulses in the spinal cord of the frog was the very first to be published in the quarterly Journal (Buchanan, 1908).

The University of Oxford never recognised Florence. Indeed, it did not award women degrees until 1920. However, University College was far more enlightened and gave Florence a DSc in 1902 (Tansey, 1993). And in 1910 she was awarded the American Association of Collegiate Alumnae’s prize for her research into the transmission of reflex impulses.

She died at the age of 62 in 1931, donating her eyes for research (Burgess, 2015). Her grave is in Wolvercote cemetery, next to that of John Burdon Sanderson.

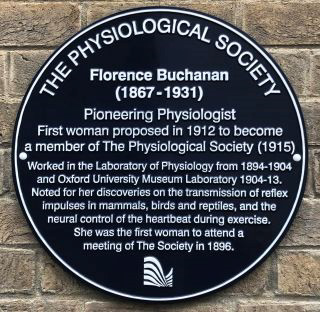

It is especially appropriate that Florence’s contributions have recently been recognised by a Physiological Society blue plaque in her honour, which flanks the entrance to what is now the Department of Physiology, Anatomy and Genetics in Oxford. Better late than never!

References

Buchanan, F (1893). Report on the polychaetes collected during the Royal Dublin Society’s survey off the west coast of Ireland. Pt. 1. Deep water forms. Proceedings of the Royal Dublin Society, Ser. n.s., 8(2), 169-179.

Buchanan, F (1894). A polynoid with branchiae (Eupolyodontes cornishii). Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science, London, New Series 35, 433-450

Buchanan F (1901). The electrical response of muscle in different kinds of persistent contraction. Journal of Physiology 27, 95–160.

Buchanan F (1908). On the time taken in transmission of reflex impulses in the spinal cord of the frog. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Physiology 1, 1–65.

Buchanan F (1909). The physiological significance of the pulse rate. Transactions of the Oxford University Scientific Club 34, 351–356.

Buchanan F (1912). Observation of the movement of the heart by means of electrocardiograms. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine 5(Clin Sect), 185–187.

Burgess H (2015). 100 years of women members: The Society’s centenary of women’s admission. Physiology News, 98, 34-35. https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.98.34

Evans CL (1964). Reminiscences of Bayliss and Starling, published for The Physiological Society. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

Heilbron JL (1974). HG Moseley: The life and letters of an English physicist 1887-1915. University of California Press. p.167.

Krogh A, Linhard J (1913). The regulation of respiration and circulation during the initial stages of muscular work. Journal of Physiology 47, 112–136.

Ross MB et al. (2022). Women are Credited Less in Science than are Men. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04966-w

Tansey EM (1993). ‘To dine with ladies smelling of dog’? A brief history of women and The Physiological Society. In Women Physiologists. Ed. Bindman L, Brading AF & Tansey

EM, pp3–17. Portland Press, London and Chapel Hill Royal College of Physicians. Sir George Seaton Buchanan. https://history.rcplondon.ac.uk/inspiring-physicians/sirgeorge-seaton-buchanan