Physiology News Magazine

From pitfalls and pressures to culturing curiosity and creativity in early career physiologists

News and Views

From pitfalls and pressures to culturing curiosity and creativity in early career physiologists

News and Views

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.130.11

Professor Damian M. Bailey

Editor-in-Chief, Experimental Physiology

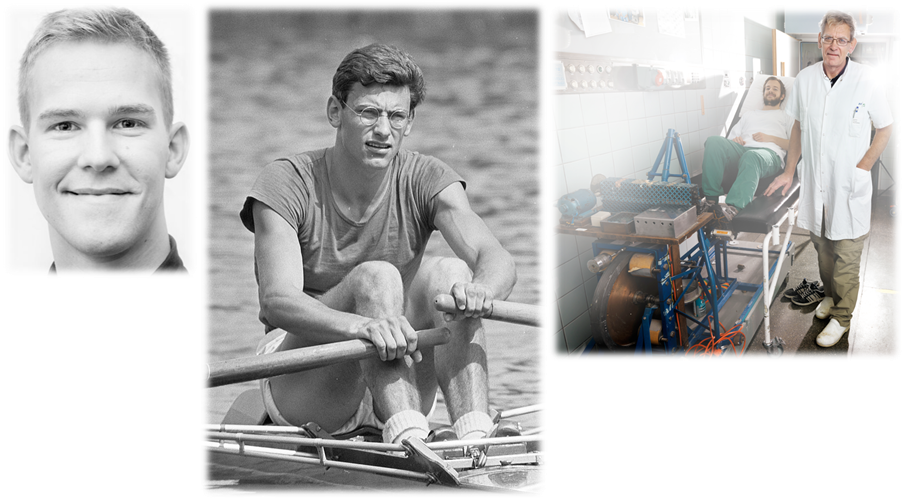

Mads Fischer

University of Copenhagen

Professor Christian Aalkjær

Aarhus University

Professor Niels H. Secher

University of Copenhagen

Life as an early career researcher (ECR) isn’t easy: from doctoral candidates and postdoctoral fellows to recently appointed independent investigators, they represent the largest and most diverse cohort of scientists (Heggeness et al., 2017), yet face unprecedented challenges that make them professionally more vulnerable in this post-pandemic era (Nature, 2020). That over half of 7,600 postdoctoral fellows from more than 93 countries surveyed by Nature considered leaving active research because of work-related mental-health concerns and fewer than half would recommend a scientific career to their younger self (Woolston, 2020), stands a clear testament to the pressures they have to endure in an ever competitive, publish or perish world. ECRs spend much of their professional careers “in limbo”, lingering in a succession of short-term contracts, battling high workloads and expectations that can derail a healthy work-life balance. The statistics are indeed sobering, with departments now struggling to recruit postdoctoral fellows (Langin, 2022) and with less than 4% of all PhD researchers going on to a permanent position at a university here in the UK (Taylor, 2010), there are calls for systemic change that will require fundamental shifts in policies, processes, power structures, norms and values. While the format of the next UK Research Excellence Framework is currently under review, it is essential that the diversity of career pathways and importance of providing adequate support to ECRs, notwithstanding the lasting impact of COVID-19, are taken into account. So spare a thought for ECRs: they are (y)our most precious commodity, the workforce of the future that we need to protect, support, and inspire, or else they will sink before they swim, perish before they publish.

It is encouraging to see just how committed The Physiological Society is to supporting ECRs with numerous initiatives that can help guide them onto that first slippery rung of a very precarious ladder towards academic progression. The Society has recently launched a new Training Hub, which provides its members with access to resources and workshops to support their career development. This includes guidance on areas ECRs have themselves identified as important, such as applying for grants, networking, publishing and presenting at conferences. The Society’s podcast also highlights some broader challenges faced by physiologists in their career, such as dealing with disappointment or juggling parenthood, with advice from experts on how to approach them. Recent addition of the Unlocking Futures Fund also provides financial support to ECR members who face a specific challenge to advancing in their career.

As part of this, Experimental Physiology is equally keen to do more for our ECRs, and I felt especially inspired having just returned from a week in Copenhagen having contributed to an annual PhD course under the auspices of the Danish Cardiovascular Academy. This course is quite unique (see below), the brainchild of the late Professor Bengt Saltin (1935-2014) whose classic “Dallas Bed Rest and Training Study” performed at The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in 1966 together with his good friend Jere H. Mitchell (1928-2021), culminated in the publication of that unforgettable monograph in Circulation (Saltin et al., 1968) that I encourage all ECRs to marvel and delight at!

Having coined (rather, proven!) that, “humans were meant to move”, Professor Saltin was quick to reach out to Professor Mikael Sander and Professor Niels H. Secher (both based at the University of Copenhagen), to establish a PhD course that later became known as ‘Integrative Human Cardiovascular Control’, to address the mechanistic bases of human cardiovascular physiology with a keen focus on the clinical translational benefits of exercise. The course was quickly established and has since gone from strength to strength, attracting students from every corner of the globe with faculty from 25 countries who represent ‘experts’ in their respective fields. Its informal and relaxed nature that sees ECRs openly engaging with Faculty Professors in a stimulating and constructive manner was an “instant hit”, providing the ideal environment to exercise their creative curiosities as they grappled with some of the more challenging, if not indeed controversial, integrated topics in physiology.

This year’s course (22 – 26 May) was special, marking its 20th anniversary, and attracted ECRs from Norway, Iceland, Switzerland, England, Wales, the Netherlands, Germany, USA, Canada, New Zealand, and the host nation, Denmark. It was organised by Mads Fischer, a PhD student at The Department of Nutrition, Exercise and Sport, University of Copenhagen under the expert tutelage of Niels Secher, Professor Emeritus, both from the University of Copenhagen and both talented oarsmen, one current, one past! Fittingly (practising what they preach), the Danish Students’ Rowing Club (DSR) at Strandvænget in Copenhagen served as the venue: the view was magical, tempting some of the ECRs to take a swim.

But it wasn’t only the view that was inspiring. With presentations as diverse as understanding how the cardiovascular system of the ‘drinking giraffe’ copes with the orthostatic challenges of gravity, physiological significance of Purkinje cell distribution within the ventricular walls of lions, rhinos, elephants and whales, to staying fit and healthy in space, we were “all” captivated! And a physiology course isn’t complete without a practical element, with two mornings dedicated to demonstrations from specialists in the field focused on cardiovascular regulation in the anaesthetised pig and echocardiography/measurement of peripheral flow in humans using ultrasound.

But perhaps the biggest highlight of all was Experimental Physiology’s inauguration of the ECR Bengt Saltin Prize. Each ECR was given three minutes and three PowerPoint slides to present their research, with two minutes for questions. The pressure to win was tangible but always constructive and congenial, at what for many, was their very first presentation on an international stage. The prize was awarded to Michael Plunkett from New Zealand, with Anantha Narayanan (also from New Zealand), and Fredrik Hoff Nordum (Norway) as runners-up, nipping closely at his heels.

The whole experience was truly inspiring and quite the breath of fresh air to watch the ECRs enjoy, engage, decompress and re-energise. I couldn’t help but think this is precisely the creative antidote to all the pressures and pitfalls that our ECRs currently face!

References

Damkjaer M et al. (2015). The giraffe kidney tolerates high arterial blood pressure by high renal interstitial pressure and low glomerular filtration rate. Acta physiologica 214, 497-510.https://doi.org/10.1111/apha.12531

Heggeness ML et al. (2017). The new face of US science. Nature 541, 21-23. https://doi.org/10.1038/541021a

Langin K (2022). U.S. labs face severe postdoc shortage. Nature 376, 1369-1370.https://doi.org/10.1126/science.add6184

Nature (2020). Postdocs in crisis: science cannot risk losing the next generation (Editorial). Nature 585, 160. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-02541-9

Saltin B et al. (1968). Responses to exercise after bed rest and training. Circulation 38, 1-78. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-71-2-444_1

Taylor M. (2010). The Scientific Century: securing our future prosperity, pp. 1-73. The Royal Society. Available online at https://royalsociety.org/topics-policy/publications/2010/scientificcentury/

Woolston C (2020). Uncertain prospects for postdoctoral researchers. Nature 588, 181-184. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-03381-3