Physiology News Magazine

How many Members of The Society have won the Nobel Prize?

Membership

How many Members of The Society have won the Nobel Prize?

Membership

Tilli Tansey

Honorary Archivist, The Physiological Society & Professor of the History of Modern Medical Sciences, QMUL, UK

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.107.44

All academic organisations do it nowadays: claim numerous luminaries, Nobel laureates and Fellows of this, that or the other, as staff, former staff or students, to enhance the perception of their lecture theatres and labs as portals to great distinctions and honours. For example, those walking along the Strand in London are assailed by photographs of the Great and Good alumni of Kings College that include many familiar names from St Thomas, Guys, Queen Elizabeth College, etc, all institutions now absorbed under the banner of KCL (www.kcl.ac.uk/aboutkings/history/nobellaureates.aspx). My own University, QMUL (Queen Mary University of London), lays claim to Nobel Prize winning physiologists Henry Dale and Edgar Adrian, on the grounds that although ultimately Cambridge medical graduates, both were clinical students at Barts Hospital, now a constituent part of the medical faculty of QMUL. Additionally, QMUL lays claim to John Vane, who joined Barts Medical College after getting the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1982. Dale, Adrian and Vane also belong to a small, select sub-group of laureates: they were Members of the Physiological Society.

How big is that group? The question is not as straightforward as it might seem. Does one count only Ordinary Members? What about Honorary Members or former Members who then win the Prize? And non-Member Nobel laureates who are then offered Honorary Membership, do they register? And how does one find all the relevant names since 1901 when the Nobel prizes were first awarded. Surely there must be a ‘List’ somewhere? Well if there is, I haven’t found it, at The Society’s headquarters, in the Archives nor in the memories of senior Members of The Society.

A recent press release asserted ‘Since its foundation in 1876, [The Society] has boasted 20 Nobel Prize winners’ (www.physoc.org/news/2016/physiological-society-announces-new-chief-executive), but in a quick back-of-the-envelope calculation I produced over 30 names without really trying. So to arrive at some definitive number, and to answer those related questions: ‘How many Members of The Society have won the Nobel Prize?’ and ‘How many Nobel laureates have been Members of The Society?’ I took myself off to the Archives, with lists of all Nobel Prize winners to date (www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/lists/all). I have searched through more than a century’s worth of Grey Books (the much valued membership lists of The Society), a sample of Committee minutes, several Secretaries’ correspondence files, usually incomplete, various candidates’ books, and numerous boxes and folders dating from 1901. None of these is completely reliable: the Grey Books never appeared on a regular annual basis and the archival collection of what was published is partial; Committee minutes, especially until comparatively recent times, are infuriatingly inconsistent: events and decisions are not always recorded, and the enactment of recorded decisions are not always reported; the Secretary’s correspondence is astonishingly varied – some files contain extensive and animated correspondence about the price of dinner, but there is little consistent correspondence with Members who had won the Nobel Prize.

Searching through all these sources, there appear to be at least 61 Nobel laureates, in Physiology or Medicine (n=55), Chemistry (n=5) or Peace (n=1), who have been Members of the Physiological Society. They divide, as expected, into two broad categories: those who were Members of The Society before winning the Nobel Prize (n=31), and Nobel laureates who were elected to The Society, principally as Honorary Members (n=30).

Both groups contain interesting anomalies and some unexpected names.

Members of The Society who won the Nobel Prize

These are predominantly Ordinary Members of the Society, those elected at a comparatively young age, regularly attending scientific meetings, presenting Communications and Demonstrations to the Society, and often serving on Society committees and editorial boards. Table 1 lists all the names in this category, in order of the year of Nobel Prize – it contains some of the best-known names in modern physiology.

Whilst space precludes describing each laureate and his work (and yes, they are all men), some general themes and specific illustrations are instructive. Intriguingly, for example, the first Ordinary Member to win was a foreign physiologist, August Krogh from Denmark, and several other foreign Ordinary Members of The Society became Nobel laureates. They include the Hungarian Albert Szent-Gyorgyi; the Belgian Corneille Heymans, and the Swedes Ragnar Granit and Ulf von Euler; John Eccles and Howard Florey from Australia; Erwin Neher and Bert Sakmann from Germany; and Herbert Gasser and Roger Tsien from the USA. In total, there are 11 foreign physiologists, most of whom having joined The Society when they were students, fellows or visitors working in the UK, and many continuing to attend Society meetings whenever in the UK.

The first ‘home-grown’ laureate was AV Hill who shared the 1922 prize (awarded in 1923) with Otto Meyerhof (of whom more later) for his work on heat production by muscle fibres, followed by Scotsman John Macleod who controversially shared the 1923 prize with Frederick Banting (of whom, likewise, more later) for their discovery of insulin. Since then, a further 13 (including the German-born, British-naturalised Sir Hans Krebs and Sir Bernard Katz, both of whom did most of their Nobel winning work in the UK) British Members of The Society have been so honoured. From the 1920s onwards, not a decade of the twentieth century passed without one or more Ordinary Members of The Society travelling to Stockholm. Many also received high civic Honours, such as knighthoods and peerages, and served in some of the most important offices in British science, including the Presidency of the Royal Society: Hopkins, Sherrington, Dale, Adrian, Florey, Hodgkin and Huxley, each of whom also received the Order of Merit.

Although the majority of these awards were in Physiology or Medicine, there were three in other categories. In 1929, Sir Arthur Harden (member 1904) won the Chemistry Prize for his work on fermentation, and almost 80 years later in 2008, Roger Tsien (Affiliate Member 1974) won the same Prize for his work on Green Fluorescent Protein. More unusual, however, is the award of the 1949 Peace Prize to the nutritionist Sir John (later Lord) Boyd Orr for his work as Director-General of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. Strictly speaking, he was no longer a Member of The Society, having resigned just a few months before being awarded the Prize, apparently because his career was moving away from science. As he had been a Member for over 30 years, and his physiological background contributed much to his Nobel-winning work, I consider he is rightly included in this category.

Tsien, like Neher and Sakmann, was an ‘Affiliate’, a class of Ordinary membership for foreign physiologists. Throughout the history of The Society, there have been several types of membership available, but from the very beginning, in 1876, there has been a category of Honorary membership, for distinguished service to The Society or the subject. Strangely, especially in light of modern practice, some laureates became Honorary Members many years after their awards; and more surprisingly, not all the Members listed in Table 1 were offered the accolade. Perhaps the most glaring exception is that of Sir Frederick Gowland Hopkins, elected in 1892, knighted in 1925, the recipient of the Royal and Copley medals of the Royal Society (1918 and 1926) and its President 1930–1935. Hopkins was co-Nobel winner in 1929 for his discovery of vitamins, but I can find no evidence that he was ever proposed for Honorary membership.

However, for many years there was a restriction on the number of Honorary Members, as will be discussed below, which may account for some of these lapses. And the delay in Nobel laureates being offered Honorary membership was sometimes due to the individual concerned: Sir Henry Dale (NP 1936) was first proposed for Honorary status in 1942, although some colleagues suggested that he would not appreciate

the honour, seeing it as acknowledgement of his retirement from active science and involvement in The Society (Dale holds

the record for serving on the Committee for 24 years, for most of which he was Chairman). Discrete enquiries confirmed this suspicion and it was only in 1951 that he eventually accepted, 15 years after his Nobel Prize. Others had even longer delays, although whether through choice cannot be determined without more research.

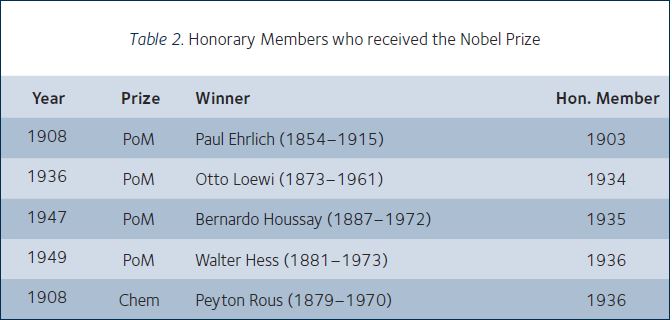

Honorary Members who won the Nobel Prize

A small, even more select group of Society Members who won the Nobel Prize (all for Physiology or Medicine) are five foreign physiologist whose work and contributions were recognised by election to Honorary membership, before their Nobel awards (Table 2). The first in this category was the bacteriologist Paul Ehrlich in 1903, and he went on to win a Nobel in 1908. Next came Otto Loewi who shared the 1936 Prize with Henry Dale for their work on elucidating chemical neurotransmission; the Argentinian Bernardo Houssay; the Swiss Walter Hess; and in 1966, the American Peyton Rous. Rous, then aged 87 and the oldest person to ever receive a Nobel Prize in Physiology of Medicine, had been an Honorary Member for 22 years. His win came 3 years after that of his son-in-law Alan Hodgkin and 40 years after his first nomination.

Nobel laureates who became Members of The Society

In recent years, Nobel prizes in Physiology or Medicine have frequently been awarded in areas far removed from ‘traditional’ physiology, and recognising this, The Society’s Executive Committee agreed in May 2003 to award Honorary membership to those not already members, noting ‘there are currently four scientists who should receive this honour‘. Since then, most British laureates (but not all), and several of the more physiological foreign laureates (but not all) have routinely been offered Honorary membership. The practice of awarding such honours to foreign physiologists does, however, have a longer history and goes back over 100 years.

In 1909, the very first Nobel laureate non-Member to be elected to Honorary membership was the Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov (NP 1905 for his work on gastric secretion), and he was followed in 1918 by Charles Richet (NP 1913), Willem Einthoven in 1924 (laureate the same year) and Ramon Y Cajal in 1931, 25 years after his Nobel award in 1906. Only 12 Honorary Members were then allowed at any one time, a maximum of six of whom could be resident in the UK. That restriction had been lifted, however, when nearly 60 years later, an occasion arose when there were Nobel laureates in what might be termed ‘mainstream physiology’ who were not already Members or Honorary Members of The Society. Thus in 1983, both David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel were elected 2 years after their Nobel awards. A curious situation, however, relates to one physiological laureate. Paul Greengard (b. 1925), who was co-laureate with Eric Kandel and Arvid Carlsson in 2000 for their discoveries concerning signal transduction in the nervous system. Kandel was elected an Honorary Member in 2008, and Carlsson the following year. Committee minutes clearly record Greengard being nominated in 2009 (along with laureates Carlsson, Hunt, Axel and Evans) but he was never elected. Why? What happened? Did he not get the invitation, or did he refuse? One former Society President recalled:

‘I cannot remember any actually turning offers down – but then these people are so shell-shocked that it is harder to decline a Physiological Society Honorary Membership offer (‘What’s that?’) than just lay back and accept all accolades’ (Jonathan Ashmore, President of Council, 2012–2014, personal communication).

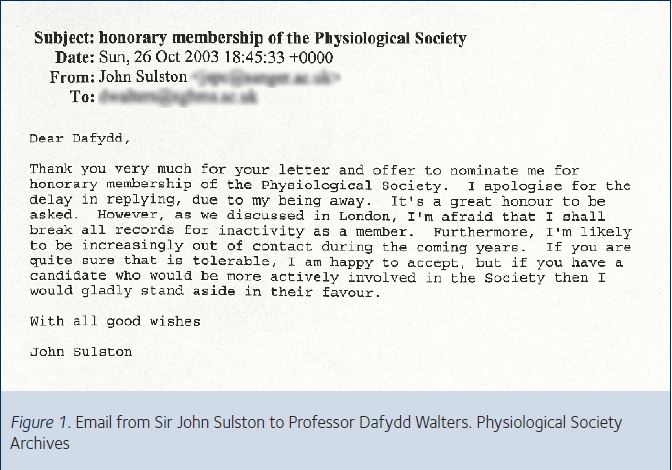

Even after that 2003 decision, there have been some strange inconsistencies: the expression ‘four scientists’ suggests the four living British Nobel laureates: Paul Nurse, John Sulston, Sydney Brenner and Tim Hunt; and indeed the first three were all elected that year. For some reason, not yet elucidated, Hunt did not join their ranks until 2009. Certainly, some recent non-physiological laureates have seemed somewhat bemused to receive such an invitation, as Sir John Sulston’s reply indicates. Refreshingly he admits he will ’break all records for inactivity as a member’ (Fig. 1).

Intriguingly, I have come across one early nomination of a ‘non-physiological’ Nobel laureate, the geneticist TH Morgan (NP 1933). In 1936, the Committee decided to offer him Honorary membership, but he appears not to have been elected, and as yet I have been unable to ascertain what happened. There may well be similar examples in the records awaiting discovery. Seeking information about more recent practice I contacted previous chairmen, one of whom recalled:

‘Re discussions on the committee in the period 1988–1994 regarding Honorary membership for Nobel laureates. I am pretty sure that this was in the context of people who were close to physiology and there was little or no discussion of winners of the Physiology or Medicine prize who were from more distant specialities. I don’t recall that we had any specific procedures – it was pretty ad hoc with committee Members simply suggesting names of possible candidates… I cannot recall any specific examples! I certainly cannot recall anyone who refused us – I think I would remember that.’ (Graham Dockray, Committee Chairman 1991–1994, personal communication).

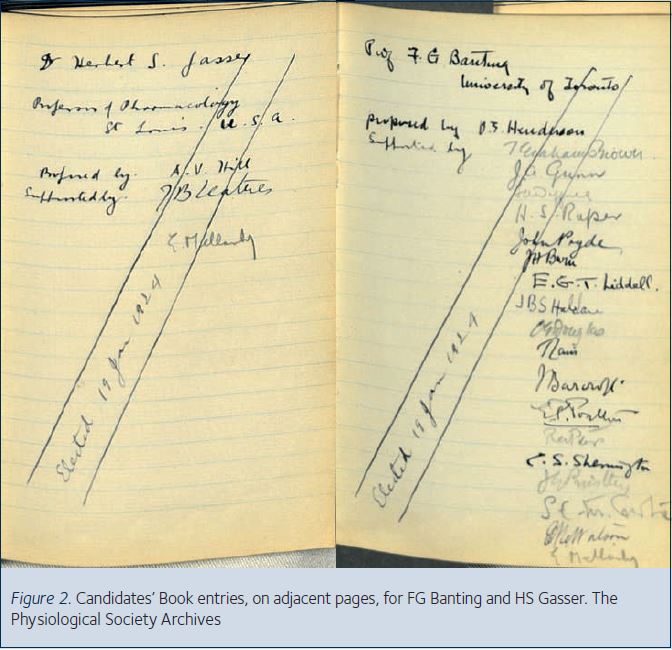

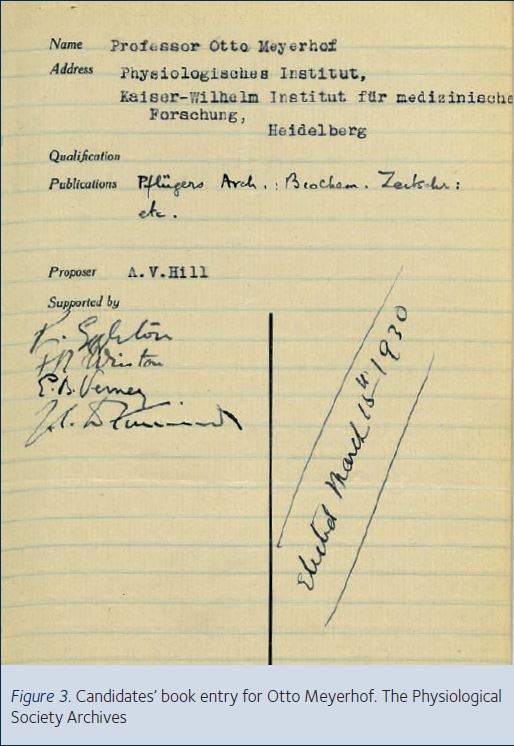

Finally, in this category there is an extremely unusual group of just two Nobel laureates, both of whom became Ordinary Members of The Society after their Nobel Prizes. Neither became Honorary Members. Both men, Frederick Banting, the co-laureate with John Macleod of the 1922 Prize, and the youngest winner of a PoM Prize, and Otto Meyerhof, co –laureate with AV Hill in 1923, were elected in the then conventional way: proposed by a Member of The Society, their names entered in a Candidates’ book which was then circulated at scientific meetings for other Members to sign in support, before being subjected to the annual ballot at an AGM.

It is not possible to determine when their names were entered, but from close examination of the Candidate’s page for Banting it is clear that he had already been proposed before his Nobel Prize was announced, by Lawrence Henderson of Harvard, not by his then boss and co-laureate John Macleod (see Fig. 2). Banting’s nomination page is adjacent to that of another future Nobel laureate, Herbert Gasser (NP 1944). Otto Meyerhof’s situation is extremely curious (see Fig. 3). He was nominated by AV Hill in 1930, 7 years after they shared the Nobel Prize (modestly that award is not recorded as a ’qualification’ on the nomination form). As yet I can find no explanation for the timing of this nomination, 7 years after the Nobel Prize. This was not the occasion when Meyerhof visited London to sign the Charter Book of the Royal Society (he was elected FRS in 1937), nor was it associated with his later flight from Nazi Germany.

The questions surrounding Meyerhof’s election epitomise several of the curiosities and inconsistencies I have unearthed in trying to answer an apparently straightforward question. I have identified 61 Members of The Society who won Nobel Prizes, but in doing so have raised more questions about some of the individuals concerned, and about the role, strategies and activities of The Society. And I’m not entirely convinced that ‘61’ is the current definitive number. It is possible that even after intense scrutiny one or two names have slipped through the net, and I would welcome further comments or suggestions.

Acknowleldgements

Many Members and staff of The Society have helped with the research for this article: Jonathan Ashmore, Jane Coppe, Graham Dockray, Casey Early, David Eisner, David Miller and Ann Silver. Unless otherwise noted, all information comes from records in The Society’s achives, held in the Wellcome Library, London. I would also like to thank Adam Wilkinson for assistance. I am supported by the Wellcome Trust.