Physiology News Magazine

It was the best of times – a postdoctoral experience in the UK in the 1960s

Membership

It was the best of times – a postdoctoral experience in the UK in the 1960s

Membership

Mordecai Blaustein

Departments of Physiology & Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, USA

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.104.32

|

|

Departments of Physiology & Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, USA |

In August 1966, my wife, Ellen, our two young children and I boarded the Nieuw Amsterdam in the former New Amsterdam, bound for the next stage of our lives: we were moving to Cambridge, England. I had just completed 3 years of Vietnam era military service voltage clamping lobster axons at the Naval Medical Research Institute (Bethesda, Maryland), and had received an NIH Special Fellowship to work in Alan Hodgkin’s laboratory. My first exposure to Cambridge dons, aside from a brief meeting with Alan a year earlier, was William Rushton, a fellow passenger on the Nieuw Amsterdam, who had been one of Alan’s mentors, and whose work was well known to me. This, of course, was the reason I was headed to Cambridge: to learn from the pioneers of cellular neurophysiology. In preparation for this experience, I had read Muriel Beadle (These Ruins are Inhabited), CP Snow (The Masters etc.) and GM Trevelyan (History of England), as well as key nerve and muscle physiology papers from the Cambridge luminaries. I was also steeped in Cambridge lore from my Washington University Medical School mentors, Daniel Tosteson and Paul Horowicz, and from W Knox Chandler, who was completing his fellowship in Hodgkin’s laboratory.

As stated in my fellowship application, my plan was to spend the Autumn squid season at the marine laboratory in Plymouth (Fig. 1), to elucidate further details of ionic conductances with voltage clamped squid axons. Upon arrival in Cambridge, however, I learned that Peter Baker, Alan’s young protégé, would lead the Cambridge contingent to Plymouth, and that he wanted ‘all hands to the (sodium) pump’. I was not totally unhappy with the change of plans, but it became a career changer. I had already mastered several research methodologies, beginning as a Cornell undergraduate studying insect metamorphosis with Howard Schneiderman, who revered Cambridge zoologist, VB Wigglesworth. At Cornell I was also introduced to H & H and the action potential by William Van der Kloot. As a medical student I worked on the Na/K-ATPase with Tosteson. During my Navy service, I learned voltage clamping from David Goldman and a brief stint at Woods Hole with John Moore and Toshio Narahashi. My main objective in going to Cambridge was to learn more about analyzing scientific questions: what are the thought processes that distinguish elite investigators? I was not to be disappointed.

Even though it was 21 years post-WW II, the UK was still feeling much more austerity than the US (the Pound, Sterling was devalued during our stay). Thus, one of the first lessons I learned was to plan experiments really carefully to conserve resources and curtail costs (and save time).

Serendipity

My first thrilling experience occurred just about 3 weeks into my fellowship. Richard (Rick) Steinhardt, Richard Keynes’ postdoctoral fellow and my Plymouth lab mate, and I discovered a large Na+ efflux from squid axons when Na+ was removed from the artificial sea water (asw) bathing the axons. This Na+ efflux was not inhibited by ouabain or K+-free asw and, thus, was not Na+ pump-mediated. Peter, Rick and I reasoned that this Na+ efflux had to be either Na+ co-transported with an anion (likely Cl–) or exchanged for Ca2+ or Mg2+, the only other cations in the asw. The simplest test was to delete the Ca2+ and, in the first experiment, we had our answer: an external Ca2+, dependent Na+ efflux, Na/Ca exchange (NCX)! What a glorious start to my traineeship!

My next major learning experience came about a month later, when Alan came to Plymouth to see how I was getting on. Alan spent a few days modeling our Na+ efflux data and helping dissect squid axons – he obviously greatly enjoyed both activities. The squid arrived at the lab in mid-afternoon so experiments were performed in the evening, and Rick and I would test the day’s model. Invariably, we would obtain a result that didn’t fit the model, but the new data would lead to a new, refined quantitative model, and a new experimental test that evening. This was a great lesson in Alan’s analytical process that has long stood me in good stead. Further, it fit his strong opinion that physiology depends critically upon hand-eye coordination and manual dexterity (i.e., the actual experiments) as well as upon the intellectual prowess to design good experiments. The only time I ever saw Alan become really upset was several years later: a competitor questioned some of his results and he rapidly retorted, ‘I did the experiments, I know they’re right!’

Peter had warned me that Alan was busy with other matters and would not participate directly in my experiments. After just a few days, however, Alan asked if I would mind if he stayed in Plymouth to work with me. To say that I was thrilled would be a gross understatement! Alan obviously was excited by our discovery, and this gave me the opportunity to work directly with the ‘great man,’ himself. Alan and I perform the initial set of our proposed Ca2+ influx experiments the following week. The very first experiment revealed that the large external Ca2+-dependent Na+ efflux in Na+-free asw was associated with a large 45Ca influx, as predicted. Voila! NCX was verified! [Note: a more detailed account of the NCX discovery is given in a PN article that I wrote with Harald Reuter (Blaustein & Reuter, 2014), who discovered NCX in mammalian cardiac muscle at the very same time we found it in squid axons.]

Occasional weekends off for ‘good behavior’

My family was living in Cambridge, where my daughter was starting primary school. Thus, during the squid season (mid-September to Christmas), I only got to see them about every third weekend. I would do an all-night experiment on Friday and then catch the early Saturday train from Plymouth to London (with a little shut-eye during the 5-hour journey). Ellen would meet me in London, and we would ‘do the town’ (museums, theatre, concerts, etc.), and then head to Cambridge late Saturday night or early Sunday to spend time as a family (Ellen had hired an Italian au pair, who stayed with the children during our London excursions). It was work hard-play hard! The London sites and cultural activities were an exhilarating change of pace, but no less exhausting.

On Monday mornings I’d take the early train to London so I could get back to Plymouth before the squid arrived. Not a squid day was to be wasted because Knox Chandler had regaled me about the devastating consequences of Plymouth gales – with no squid for days afterward. One fortuitous aspect of the early train ride was my almost invariable meeting with Andrew Huxley who was then Chair of the University College Physiology Department. He lived in Grantchester, and would usually take the early Monday train to London where he would spend much of the week. Andrew was very generous with his time during those trips, and I got to know him much better than might have been the case if we met only at Phys Soc meetings. Indeed, that friendship lasted until his death. Hugo Gonzales-Serratos, who was Andrew’s research student in the mid 1960’s, joined the Biophysics Department at the University of Maryland in 1979, at the time I became Chair of Physiology. We arranged for Andrew to visit the University of Maryland on several occasions, including once to present a named lecture. During one of my visits to Cambridge in the 1980’s, I was Andrew’s guest at Trinity where he was the Master. He guided me on a most memorable tour of the Wren Library and some of its greatly prized books, including Newton’s own copy of the Principia – a special treat for a book lover and book collector (and the son of a book publisher and collector).

A family affair

At the end of the 1966 squid season, in mid-December, I rejoined my family in Cambridge – and learned that my Jewish daughter had been appropriately selected to play the Virgin Mary in her school’s Christmas Pageant. Alan had been so enthused about our squid results that he went back to Plymouth early in January for a few more experiments on the last of the season’s squid – but he forbade me to leave my family and join him. The next January, I took my family to visit Plymouth while I completed a last few experiments for our J Physiol NCX and Na+ pump papers.

While I was in Plymouth, my ‘squidow’ (local term for wives left behind), Ellen, was busy making new friends – especially amongst the Cambridge ‘transients.’ One was Marcella Ross, whose husband, Leonard, a neuroanatomist from Philadelphia, was on sabbatical. Ellen invited them to dinner, where I learned about Len’s work on the structure of isolated nerve endings (synaptosomes) in Victor Whittaker’s laboratory in the Biochemistry Department. I was immediately intrigued by the possibility that synaptosomes might be amenable to physiological study. Thus, at my first opportunity, I visited Len and Roger Marchbanks in their lab (Victor was away). Indeed, my first published study after returning to the States was on NCX in synaptosomes (Blaustein & Wiesmann, 1970). This was just the first of >50 studies on the physiology of synaptosomes that my trainees and I performed over the next three decades – including many published in J Physiol. Obviously, one of the other wonderful benefits of my UK experience was the opportunity to interact with numerous outstanding scholars – trainees as well as mentors. Frequent gatherings for afternoon tea or a pub lunch with fellow trainees such as Leroy (Roy) Costantin, Virgilio Lew and Stephen Easter, and with Richard (Lord) Adrian and Ian Glynn, as well as Peter Baker, enabled us to test new ideas on a very critical audience. I rapidly learned, however, that a half-pint of bitters was my limit at the pub if I wanted to do any work in the afternoon – but bartenders often mistook my American English ‘half’ for ‘have,’ and served a full pint. My friendship with Roy led to his recruitment to the Washington University (St. Louis) Medical School Physiology & Biophysics Department, where we were colleagues until his untimely death.

Work in Cambridge was a little less hectic than in Plymouth – and we didn’t have to worry about a fickle squid supply. Peter was anxious to extend our NCX studies so I agreed to measure Na+-dependent Ca2+ fluxes in spider crab (Maia squinado) nerves. The results were reported in our first NCX paper (Baker & Blaustein, 1968). The full (J Physiol) squid papers didn’t get published until a year later, but we presented those results at meetings of the Phys Soc. I was especially nervous at my first presentation, in the Spring of 1967, because I was forewarned to beware of penetrating questions from Andrew Huxley and Bernard Katz. Their questioning turned out to be quite mild; our findings spoke for themselves.

The squid call again

I returned to Plymouth in September 1967, and Alan joined me for part of the squid season. We had planned many of the experiments beforehand, and were able to complete virtually all of the proposed NCX studies. I also finished work for our Na+ pump paper (the original objective of the previous season). Two other Americans came to Plymouth that year – Larry Cohen (Richard Keynes’ fellow) and Bertil Hille (Alan’s fellow), so there were lively, broad-ranging discussions at morning coffee and afternoon tea. Also participating were more senior scientists including visitors such as Trevor Shaw and Peter Caldwell, and Eric Denton, a permanent member of the Plymouth laboratory. A seasonal highlight was a Thanksgiving feast (on Saturday, because Thursday was a squid day) for both the American and British squidders. The venue was, appropriately, not far from the ‘Mayflower Steps’, the site from which the Pilgrims had embarked for Plymouth, Massachusetts in 1620. As the only ‘medically-qualified’ attendee, it fell on me to carve the turkey in front of all – and, to the embarrassment of the (non-British) chef, I quickly discovered an unopened bag of giblets still inside the deliciously roasted bird.

Threads of life

While I was away (again), Ellen befriended our new next-door neighbors, Joy and Mani Matter. Mani, the Bern, Switzerland, Town Counsel, was studying international law. Joy, a teacher, later became Education Minister for the Canton of Bern. Mani’s avocation was satirical song writing and singing in Swiss-German dialect, and he became a folk-hero. Our friendship blossomed through the spring, with evenings spent reading poetry and plays together; it continues with Joy to this day (Mani died in a tragic auto accident in 1972). That friendship also contributed to our decision to go to Bern in 1971, where I did a ‘mini-sabbatical’ in Harald Reuter’s laboratory – another turning point in my career. Harald and I discovered NCX in mammalian arteries. That inspired my proposal that Na+ pumps, NCX and an ‘endogenous ouabain-like compound’ (the ‘holy spirit’) contribute to the pathogenesis of hypertension (Blaustein, 1977). In turn, that led to the discovery, with John Hamlyn (my co-worker and former trainee) and our colleagues at the Upjohn company, that ouabain is, in fact, a mammalian hormone. (Coincidentally, John was a pre-teenager growing up in Plymouth during my traineeship days.) This latter phase of my career is, in part, summarized in two new reviews (Blaustein et al., 2016; Hamlyn & Blaustein, 2016).

Cambridge/Plymouth contemporaries and mentors

I spent the Spring of 1968 writing the three J Physiol papers on our squid work, while also exploring other preparations in which to study NCX. Given the fine research on red cell cation transport, especially the Na+ pump by, e.g., Glynn and Lew, and Tosteson and Joseph Hoffman), I tested human, cow, pig and even nucleated chicken erythrocytes, but came up empty-handed. A decade later, John Parker discovered NCX in dog red cells, which have no Na+ pumps; they employ an ATP-driven Ca2+ pump to generate a Ca2+ gradient, which NCX then uses to extrude Na+. The evolutionary pressures that led to these family differences in erythrocyte ion regulation are fascinating to contemplate.

I was not a member of a Cambridge college, but was periodically invited to lunch or dinner or to a college feast – always enjoyable occasions. One ‘ordinary’ dinner was particularly memorable. I had volunteered to be a subject for one of Patrick Merton’s studies on the control of muscle movement and, following the experiment, he invited me to dine at Trinity. After dinner, Pat suggested that we stay for port, and he and I remained at High Table with several senior dons, in candlelight, under the glare of Henry VIII. The elder dons, each of whose age was more than the sum of Pat’s (47) and mine (32), proceeded to discuss a 1946 meeting of the Cambridge Moral Science Society that they had attended with Ludwig Wittgenstein (MSC chair), Karl Popper (invited guest from LSE) and Bertrand Russell. I was enthralled (and speechless) – as was Pat – it was surreal. Only about 5 years ago, when I read ‘Wittgenstein’s Poker’ (Edmonds & Eidinow, 2001), did I grasp the significance of this first-hand recounting. The dons had borne witness to the (in)famous brief confrontation about whether philosophy dealt with substantive problems (Popper) or mere linguistic puzzles (Wittgenstein, who brandished a fireplace poker for emphasis). Popper used Wittgenstein’s waving of the poker as an example of a ‘substantive philosophical problem’. When Russell asked Wittgenstein to put down the poker, he threw it down and stormed out. Only in Cambridge!

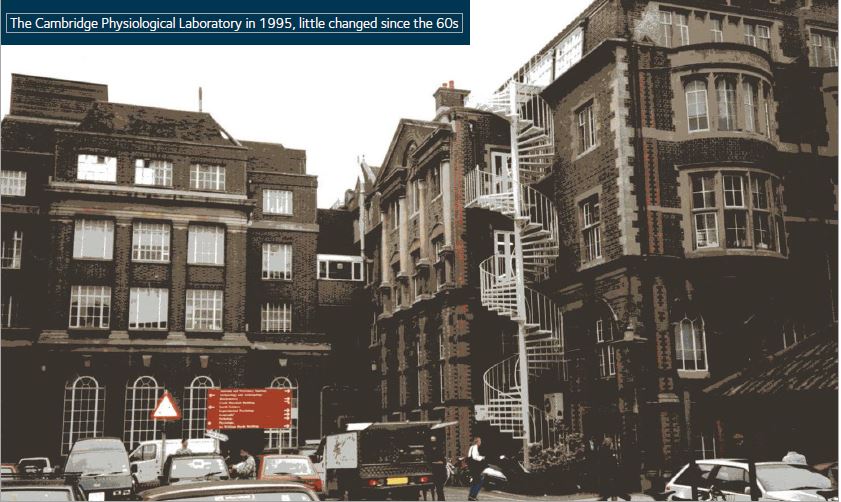

As I cycled past King’s College Chapel, en route to the Physiological Laboratory every morning, I would pinch myself to be sure that it wasn’t just a fairytale. To a bright-eyed and bushy-tailed youngster from ‘the Colonies,’ it was exhilarating. I was delighted to be up to the task – not only absorbing information, but contributing new ideas. The exceptional intellect of our mentors surely was a major factor, but I daresay that equally important was input and criticism from my contemporaries. It is noteworthy that all the trainees with whom I had extensive interactions at Plymouth and Cambridge (mentioned above) went on to illustrious academic careers. It was, truly, a special time and place!

References

Baker PF & Blaustein MP (1968). Sodium-dependent uptake of calcium by crab nerve. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 150:167-170.

Blaustein MP (1977). Sodium ions, calcium ions, blood pressure regulation and hypertension: a reassessment and a hypothesis. Am. J. Physiol. 232:C165-C173.

Blaustein MP, Chen L, Hamlyn JM, Leenen FHH, Lingrel JB, Wier WG & Zhang Z (2016). Pivotal role of a2 Na+ pumps in cardiovascular health and disease. J. Physiol.

Blaustein MP & Reuter H (2014). A tale of three cities: the discovery of sodium/calcium exchange and some of its implications. Physiol. News 96 (Autumn 2014):32-37.

Blaustein MP & Wiesmann WP (1970). Effect of sodium ions on calcium movements in isolated synaptic nerve terminals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 66:664-671.

Edmonds D & Eidinow J (2001). Wittgenstein’s Poker. Harper Collins Press, New York, 340 pp.

Hamlyn JM & Blaustein MP (2016). Endogenous ouabain: recent advances and controversies. Hypertension 68:526-532