Physiology News Magazine

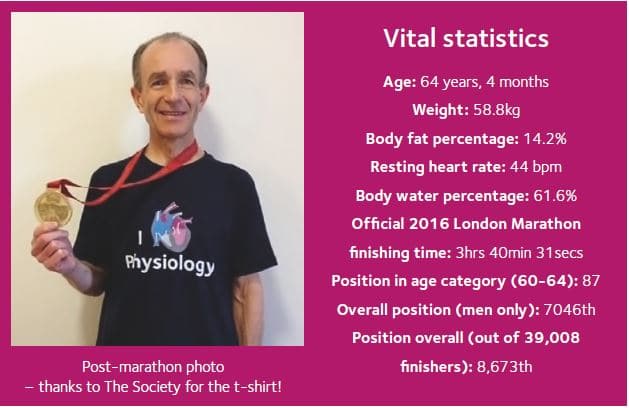

Marathon Man

Letters to the Editor

Marathon Man

Letters to the Editor

David Howells

Father of Sally Howells, Managing Editor, The Journal of Physiology

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.104.6b

- As an experienced marathon runner, I have several physiological questions, and wonder whether an energy drink would have saved the original marathon runner in 490 BC? In many ways the marathon is a ridiculous distance. Some say, a reasonably fit runner could cope with 20 miles relatively easily. But those additional six (and a bit) miles make the marathon a real challenge. The rationale seems to be that the human body typically runs low on carbohydrate as fuel after about 20 miles of running and resorts to burning fat. Is that right?

- Over the years, I have experimented with taking on isotonic energy drinks and gels throughout the run. But frankly, I’m not convinced they made a real difference. This year I only had water – nothing else – and didn’t feel any worse or better. My question is: all other things being equal, is there physiological evidence that so called energy drinks (or any other supplement, for that matter) stimulate the body to produce enough carbohydrate to last 26.2 miles? Or is it simply all in the mind?

- I started running marathons in the early 1980s. The advice then was to drink lots of water. Concerns about the risk of dehydration abounded. Views have changed. My strategy for the recent marathon was to drink just water every five or six miles. I did feel a bit rough at about mile 23 (a mind issue?), but wasn’t craving the sickly energy drinks at any time during the run. Maybe the more water one drinks, the more one craves for energy drinks to increase the concentrate of sodium in the body. Do we really need those energy drinks if we get our hydration levels right?

- The roughest I have ever felt after a run was immediately following a 44 mile training run (back in the 1980s) when I was preparing for an 80 mile ultra run. I was well supported and took on lots (and I mean lots) of water about every five to seven miles. I felt ill for about three days. Someone suggested I needed to take salt tablets on the 80-miler (branded energy drinks were not quite as fashionable then). I did, and I have to admit that I experienced none of the same adverse effects.

- Every time I have had a post marathon massage (courtesy of the MS Society for whom I usually run), my recovery has been very good (i.e. I can walk normally the next day). During the post-run massage this year, the physiotherapists were fascinated by my leg muscles, which were twitching wildly. It’s something that I’m well used to, but gets more exaggerated after a long run. What causes this? I’d love to know.

My grateful thanks to all those at The Physiological Society who so generously supported the MS Society by sponsoring me this year.

Ron Maughan, Emeritus Professor of Sport and Exercise Nutrition at Loughborough University, wrote to the Editor in response:

- There is some truth in the idea that fat is the main fuel after about 20 miles, but fat and carbohydrate are both used as fuels throughout the race. It is certainly true, though, that once the body’s carbohydrate stores (glycogen in the liver and muscles) are depleted, high intensity exercise is not possible (Bergstrom et al., 1967). We can run using almost entirely fat, but not at a fast pace. Training and dietary strategies are therefore generally aimed at using as much fat as possible to spare the limited glycogen (that’s the training part), maximizing glycogen stores before the start (that’s the diet part) and then also consuming some more carbohydrate during the race. Remember that if you burn only fat, you need about 7% more oxygen than if you burn only carbohydrate: 1 litre of oxygen gives about 4.7 kcal on fat but about 5.0 kcal using carbohydrate. When oxygen supply is limited, burning carbohydrate makes sense. This has been known for a long time, but has been almost entirely forgotten (Zuntz, 1901)

- Studies have generally shown that ingesting carbohydrate during exercise makes the exercise feel easier (as shown by Krogh and Lindhard (1920)) and can improve performance (as suggested by studies at the Boston marathon in the mid-1920’s (Levine et al., 1924) but not convincingly shown until much later. Within the last few years, some studies have shown that periodically rinsing the mouth with a carbohydrate drink and spitting it out can improve performance, even though none of the drink is swallowed (Carter et al., 2004). Whether that is in the ‘mind’ or not, I am not sure, but there is no doubt that fatigue is more a matter of central nervous system function that of muscle function, as stated so clearly by Francis Bainbridge in his 1919 monograph of The Physiological Society which was and remains one of the best ever texts on exercise physiology (Bainbridge, 1919). Once again, this seemed to be forgotten by exercise physiologists of the latter part of the 20th century.

- Most serious runners NEVER drink in training, even on long runs on hot days, unless they are practising their drinking strategy in preparation for a race. There is no obvious benefit to drinking in training apart from learning what works for you, to practise the mechanics of drinking and training the gut to cope with the presence of fluid while running. But remember that most energy drinks contain little or no electrolytes. The main electrolyte lost in sweat is sodium (and chloride) but the concentration varies greatly – anything from about 20-80 mmol/l (Shirreffs and Maughan, 1997). Most mainstream sports drinks contain about 20-35 mmol/l sodium – any more and it tastes salty. Remember that most of these are consumed as soft drinks, so taste is all-important. When sweat losses are very high, an Oral Rehydration Solution (ORS – intended for replacing water and salt losses in severe diarrhoea) may be more appropriate as these usually contain about 60-90 mmol/l sodium.

- Drinking too much plain water will dilute the plasma sodium concentration and likely produce symptoms like those described. Very occasionally, it can be fatal, but you really have to drink a lot for that to happen (Hew-Butler et al., 2015).

- I’d love to know too! This sometimes happens before muscles go into cramp, but no-one really knows what causes cramp either. We have tried to find out, so maybe we can get you to volunteer for some experiments (Maughan, 1986).

Bainbridge FW (1919) The Physiology of Muscular Exercise. London Longmans, Green and Co

Bergstrom J, Hermansen L, Hultman E & Saltin B (1967). Diet, muscle glycogen and physical performance.

Acta Physiologica Scandinavica 71, 140-150

Carter JM, Jeukendrup AE & Jones DA. (2004). The effect of carbohydrate mouth rinse on 1-h cycle time trial performance. Med Sci Sports Exerc 36, 2107-2111

Hew-Butler T, Rosner MH, Fowkes-Godek S, et al (2015). Statement of the 3rd International Exercise-Associated Hyponatremia Consensus Development Conference, Carlsbad, California, 2015. Clin J Sports Med 25, 303-320

Krogh A, Lindhard JL (1920). The relative values of fat and carbohydrate as sources of muscular energy. Biochemical Journal, 14, 290-363

Levine SA, G Burgess, CL Derick (1924). Some changes in the chemical constituents of the blood following a marathon race With special reference to the development of hypoglycaemia. JAMA 82(22), 1778-1779

Maughan RJ (1986). Exercise-induced muscle cramp: a prospective biochemical study in marathon runners.

J Sports Sci 4: 31-34

Shirreffs SM, Maughan RJ (1997). Whole body sweat collection in man: an improved method with some preliminary data on electrolyte composition.

J Appl Physiol 82, 336-341

Zuntz N (1901). Über die Bedeutung der versehiedenen Nährstoffe als Erzeuger der Muskelkraft.

Pfluger’s Arch 83, 557-571