Physiology News Magazine

Member profile: Paul Thomas

The Imaging Facility Manager at the University of East Anglia, UK, tells of his journey from biochemist to ‘born-again’ physiologist to bioimager, and the gratification of hosting trainee imaging courses (funded by The Society).

Membership

Member profile: Paul Thomas

The Imaging Facility Manager at the University of East Anglia, UK, tells of his journey from biochemist to ‘born-again’ physiologist to bioimager, and the gratification of hosting trainee imaging courses (funded by The Society).

Membership

Paul Thomas

Imaging Facility Manager, University of East Anglia, UK

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.95.44

‘…thank you for the wonderful imaging course… all of us as participants will always have it as a reference point as we begin our “voyage of discovery” in the world of biomedical imaging.’ These words were written by a trainee at the end of one of my annual Society-funded workshops on live-cell imaging. In addition to being a rather nice compliment, for me the words also encapsulate one of the two most gratifying things about doing academic science: helping a young scientist at the start of his or her research career. During my own research career, I’ve been fortunate to find mentors who were both brilliant teachers and extremely generous with their time and knowledge. And it was while working with the first of these individuals that I chanced upon the second area of science that I find especially rewarding: that intoxicating (and generally elusive) moment when you see your own experimental predictions proved correct.

It happened during my first job after graduation. I was sitting rather nervously in front of an electron microscope with my boss, David Allan, and our collaborator Tony Limbrick. I had prepared ‘Triton shells’ from chicken erythrocytes treated with the ionophore A23187 in the presence of various inhibitors, and we were looking to see the effects on the cytoskeleton. First, we checked the controls, which to my relief showed a large black nucleus encircled by the marginal band of microtubules, with a meshwork of intermediate filaments sandwiched in between. Next came the sample treated with ionophore alone and, as expected, all we saw were bare nuclei – the increase in intracellular calcium had caused the total disappearance of the cells’ cytoskeletons. Finally, as Tony loaded one of the samples with the inhibitors, I piped up with, ‘Now in this one we should see the nucleus and intermediate filaments, but no marginal band.’ And for the first time in my career, I got it right! The images we obtained that day took centre stage in my first publication as first author. Coincidentally, it was also the first publication in which I had a direct role in the microscopy.

Nevertheless, the path to my present position as a dedicated bio-imager was by no means straightforward. Starting out with a joint honours degree in Physiology and Biochemistry, I had always considered myself a physiologist rather than a biochemist. However, after graduation, I discovered that jobs in biochemistry were more plentiful, so when David (a newly appointed lecturer and lipid biochemist) offered me the opportunity to work in his lab at University College Hospital Medical School, I snapped it up. As I’ve already alluded to, David’s interests were in how intracellular calcium affected erythrocyte shape, and from then on calcium would form the focus of my research career.

From London I ventured across the Atlantic to California where I used my experience in inositol-lipid metabolism to investigate calcium signalling in spermatozoa. My professor, Stanley Meizel, was one the most generous mentors anyone could wish for, and he convinced me to stay and study for my PhD while providing me with the vital support I needed. Ever since, I’ve tried to emulate his thoughtful approach in working with young scientists.

If Stan was the most inspiring influence in my career, it was Wolfhard Almers who was the most influential in developing my quantitative skills as a research scientist. On finishing my PhD I decided I could either go the ‘molecular’ route, or the ‘single-cell’ route. I chose the latter after having been profoundly impressed by a seminar in which Wolf described his work on measuring the properties of the fusion pore of single secretory vesicles. It was during my time with Wolf that I was ‘born-again’ as a physiologist and my work with him increasingly relied on microscopy. Nevertheless, it would be several more years and two more jobs before I would become an out-and-out ‘imager’.

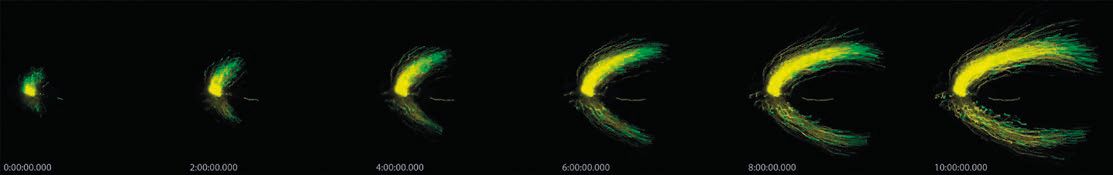

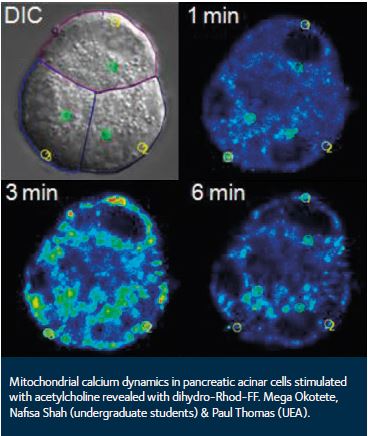

Returning to England via another stint in California, I obtained a Fellowship in Pharmacology at Cambridge University. While there I was awarded a grant in ‘Bioimaging’ – an initiative run by the BBSRC. In this work, my post-docs and I used time-differential analysis of brightfield images, in conjunction with fura-2 measurements, to investigate the regulation of exocytosis in individual pancreatic acinar cells. The results were subsequently published in The Journal of Physiology.

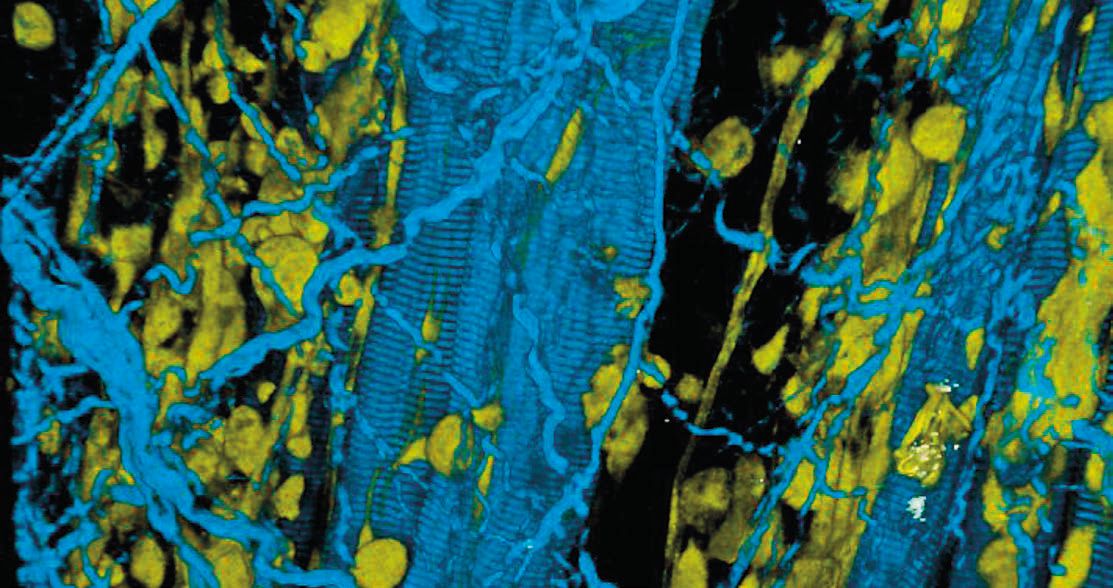

And so it was the acquisition of these imaging skills that led inexorably to my present appointment as the Manager of the Imaging Facility at UEA. In this role my greatest satisfaction comes from the training of young scientists, especially those that I’m privileged to teach in the course of running The Society’s workshop every summer. Obviously it’s always a pleasure to receive positive feedback from workshop participants, but it’s even more rewarding to know that I might possibly have made a critical contribution to someone’s research career as they embark on their own ‘voyage of discovery’.