Physiology News Magazine

Mind and mend the gap: Women in physiology

Editor-in-Chief, Experimental Physiology

News and Views

Mind and mend the gap: Women in physiology

Editor-in-Chief, Experimental Physiology

News and Views

Professor Damian Bailey

Editor-in-Chief, Experimental Physiology

I’m writing this column a few days after 11 February, which marked the (eighth) International Day of Women and Girls in Science, an opportunity to celebrate creativity, innovation and achievements while continuing the global mission towards gender equality. In her opening address to this year’s Assembly held at the United Nations (UN) Headquarters in New York City, Audrey Azoulay, Director-General of the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) remarked, “Science is many things: a study of natural, physical and social phenomena; a process to test hypotheses and draw conclusions; a journey of discovery to understand the world’s many mysteries. But what science should be is equitable, diverse and inclusive. It should be for all and open to all, especially women.”

But as we know all too well, best wishes don’t always stack up against the stark truths of reality, with the latest UNESCO Science Report highlighting a “leaky pipeline”: only 35 per cent of graduates in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM)- related fields and 28% of all researchers are women (United Nations Educational, 2022). This is clearly out of kilter with what would be expected based on population demographics and an estimated 3.905 billion women that represent 49.58% (let’s round this up to 50%) of the world’s population (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2022). More needs to be done to “mend” the gender gap, and it’s the steady drip, drip, drip of cultural change that will ultimately help wear away this stubborn stone.

The day’s events have given me an opportunity to quietly reflect on our own specialist discipline and the common challenges facing our community. That women physiologists are underrepresented has not gone unnoticed by The Physiological Society (TPS), having led on a number of initiatives that challenge stereotypes and long-standing biases, while looking to raise awareness of those physiologists blazing new trails (Society, 2013). The recent launch of the TPS’ Equity, Inclusion and Diversity Roadmap stands clear testament to its commitment to champion diversity, promote inclusivity, and strive for equity providing opportunities fairly and squarely for all.

A trip down memory lane helps put the challenges women physiologists faced into clearer perspective with a canonical example that holds special relevance to readers of Experimental Physiology. Dr Florence Buchanan (1867–1931) was one of our earliest “trailblazers” whose name will be forever etched into TPS’ history books, given some “fearless firsts” that challenged the status quo (Burgess, 2015; Tansey, 2015; Ashcroft, 2022). Much to the disdain of others (male members), she was the first woman to attend a meeting of TPS in 1896 some 22 years after it was founded, although she did not join the men for dinner, which at the time hosted live animal experiments and was the highlight of the meeting. Ernest Starling (1866–1927) voiced his concerns, stating “it would be improper to dine with ladies smelling of dog – the men smelling of dog that is” (Evans, 1964). She was also the first to publish in the Quarterly Journal of Experimental Physiology that later became Experimental Physiology in 1990, with a 67 page (no less!) original article focused on the transmission of reflex impulses in the frog (Buchanan, 1908). And her third first, fueled by a relentless persistence that included at least ten communications to TPS and a smattering of papers published in the Quarterly Journal of Experimental Physiology (3) and The Journal of Physiology (2), she became the first (alphabetically) of six women to be elected for membership to TPS at the AGM in January 1915: much thanks to a postal ballot bravely proposed by J. S. Haldane (1860–1936) and J. N. Langley (1852–1925) that took place the year prior, culminating in the landmark “Rule 36”: “Women shall be eligible for membership of The Society and have the same rights, duties and privileges as men.” Dr Buchanan challenged tradition and broke the mould: she was surely made of the “right stuff”! Her legacy was celebrated by TPS on 4 July 2022, with the unveiling of a Blue Plaque at The Department of Physiology, Anatomy and Genetics at University of Oxford, UK where Buchanan worked as a research assistant under the tutelage of John Burdon-Sanderson (1828–1905).

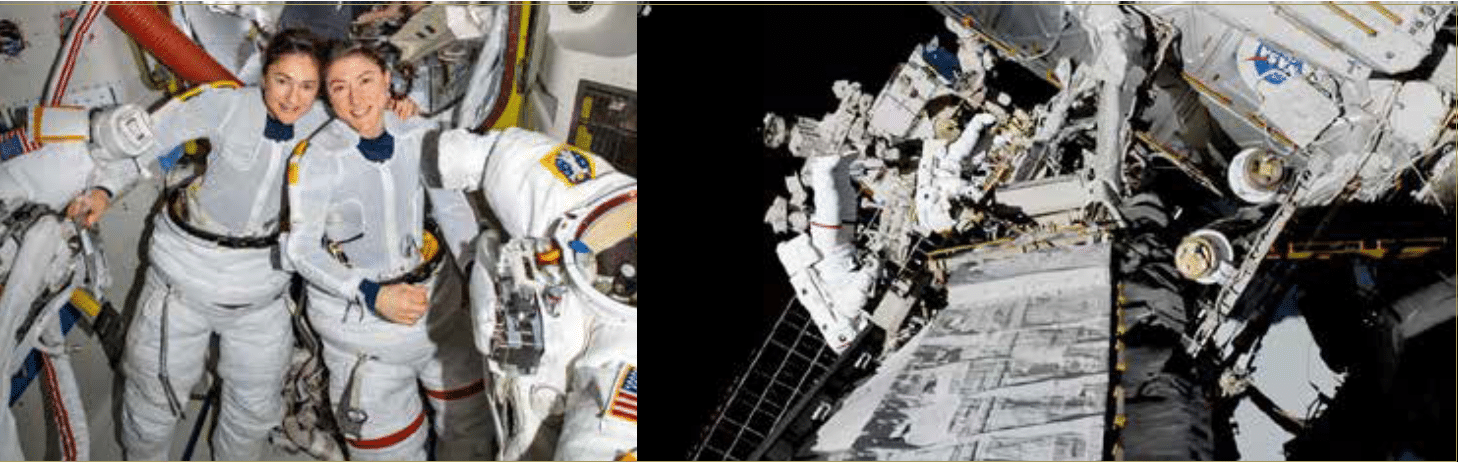

We’ve come a long way since. A shining example that reflected modern society’s changing attitudes towards sex and gender presented itself on 18 October 2019 when NASA astronauts Christina Koch and Jessica Meir performed the first “all-women” spacewalk on the International Space Station, a truly historic milestone (Fig.1). What’s especially poignant is that Jessica Meir is a physiologist having studied vertebrate adaptation to extreme environments (there is no better example than humans surviving in the vacuum of space!): topics that she covered during her delivery of The President’s Lecture at TPS in 2021. And NASA’s commitment, through its Artemis missions, to land the first woman (and first person of colour) on the Moon with an orbital outpost to support human exploration of Mars, will inspire future generations of like-minded trailblazing women. There’s good reason why we need more women “astro-physiologists” to solve the complex challenges of deep spaceflight! (Bailey, 2022).

But there’s still a long way to go as undercurrents of sex and gender bias persist (Barrett, 2019). Publishing papers, the primary currency of academe and established metric for tenure and promotion, highlights a systemic problem, with women much less likely than men to be credited with authorship (Ni et al., 2021; Ross et al., 2022). That their contributions are devalued or simply not recognised may account, at least in part, for the well established “productivity gap” understandably compounded by the COVID pandemic (Andersen et al., 2020; Huang et al., 2020) further discouraging career progression within junior ranks. And at the very sharp end of life and death, spare a thought for those (seemingly) obvious anatomical/physiological differences (Tarnopolsky and Saris, 2001; Ansdell et al., 2020) best encapsulated by that famous saying, “men are from Mars and women are from Venus”. Despite existing legislation such as the National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act of 1993 mandating the inclusion of women in studies of humans, the field of medicine consistently fails to account for differences in sex and gender. This puts women’s healthcare provision at risk, with prescriptions and diagnoses confounded by approaches that overly favour male physiology (Miller, 2014; Nowogrodzki, 2017). On a more positive note, this is a rich plot for physiologists to plunder.

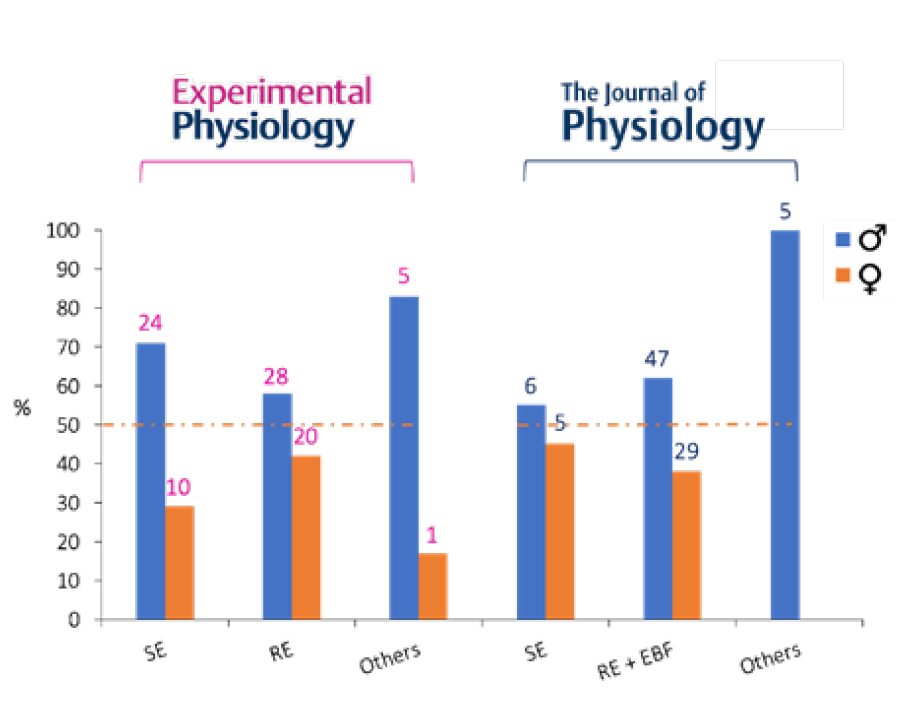

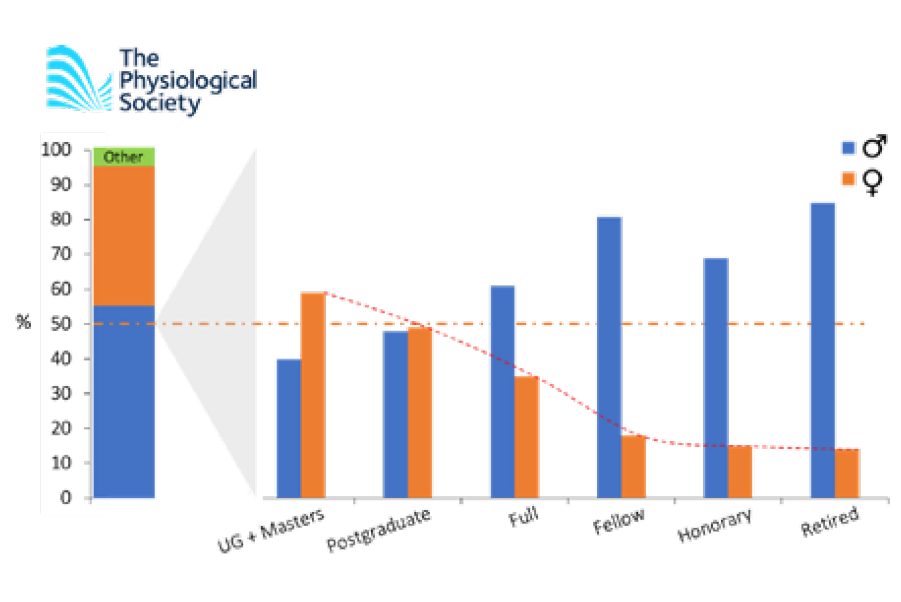

I’ve become acutely aware of this “unconscious” bias, borne through bitter experience and by taking the time to reflect and refer to the literature base as I write this column. The sobering reality of directing a male dominated laboratory, reality checks when composing submissions to the Research Excellence Framework and only a handful of women scientists with whom I’ve collaborated in my specialist field highlights a personal failing. Even a cursory glance at the Editorial Boards of Experimental Physiology and the Journal of Physiology expose “fault lines” within their composition (Fig.2), which is commonplace across the life sciences (Palser et al., 2022). Under-representation of women is equally apparent across a number of categories within TPS membership that appears to be compounded with age since the disparity is especially pronounced in the fellow, honorary and retired categories that typically attract older members (Fig.3). I wonder if this reflects the bitter aftermath of times gone past, with fewer women remaining in physiology, shackled by cultural constraints?

More steady drips needed, I hear you say? We all have a role to play and it’s a long road ahead, after all, it’s all about mutual respect and accountability (see Peter Kohl’s column on p10). If the “leaky” pipeline is indeed age-related, there is a message of hope since we have an opportunity to provide (more) support to our younger women physiologists. This is a change that both Peter Kohl and I want to actively support and promote, indeed as those Editors-in-Chief that stood before us. We can look beyond our shores and take strength and learn from a number of new initiatives. The Royal Society of Chemistry’s Joint Committment for Action on Inclusion and Diversity, mapping out the steps they will take to minimise bias across their family of (>1500) journals and sharing it with other publishers to make scholarly publishing more inclusive and diverse is a leading example. So too is the recent decision of a subset of Nature Portfolio journals where submitting authors will be prompted to provide details on how sex and gender were considered in study design (2022), encouraging compliance with SAGER (Sex and Gender Equity in Research) guidelines (Heidari et al., 2016).

And on a more personal note, I’m keen to attract more women physiologists to the Editorial Board of Experimental Physiology to redress the current imbalance and ensure that women are visually represented alongside their male contemporaries: if you are interested in contributing either as a Senior or Reviewing Editor, please feel free to get in touch. In closing, I’ll end this column with a simple equation, taken from Antonio Guterres, Secretary General to UNESCO: ↑women +↑girls in science = ↑volume + ↑quality science.

Simple.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professor Peter Kohl (Editor-in-Chief of The Journal of Physiology) and Dariel Burdass [The Physiological Society (TPS)] for stimulating discussions and helpful reference to key literature sources. Josh Hersant (TPS) and Andrew MacKenzie (TPS) kindly provided the raw data supporting Figures 2 and 3 respectively.

References

Editorial (2022). Nature journals raise the bar on sex and gender reporting in research. Nature 605, 396. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-01218-9

Andersen JP, et al. (2020). Meta-Research: COVID-19 medical papers have fewer women first authors than expected. Elife 9, e58807.

Ansdell P, et al. (2020). Physiological sex differences affect the integrative response to exercise: acute and chronic implications. Experimental Physiology 105, 2007-2021.

Ashcroft F (2022). Florence Buchanan: A true pioneer. Physiology News 127, 46-47.

Bailey DM (2022). Inspired by space physiology: shoot for the stars and believe in the beyond! Physiology News 128, 12-13.

Barrett KE (2019). Towards gender equality in scientific careers: Are we there yet? … Are we there yet? … Are we there yet? Physiology News 115, 46-47.

Buchanan F (1908). On the time taken in transmission of reflex impulses in the spinal cord of the frog. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Physiology 1, 1-66.

Burgess H (2015). 100 years of women members: The Society’s centenary of women’s admission. Physiology News 98, 34-35.

Evans CL (1964). Reminiscences of Bayliss and Starling, published for The Physiological Society. ed. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Heidari S, et al. (2016). Sex and Gender Equity in Research: rationale for the SAGER guidelines and recommended use. Research Integrity in the Biomedical Sciences 1, 2.

Huang J, et al. (2020). Historical comparison of gender inequality in scientific careers across countries and disciplines. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 117, 4609-4616.

Miller VM (2014). Why are sex and gender important to basic physiology and translational and individualized medicine? American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 306, H781-788.

Ni C, et al. (2021). The gendered nature of authorship. Science Advances 7, eabe4639.

Nowogrodzki A (2017). Clinical research: Inequality in medicine. Nature 550, S18-S19.

Palser ER, et al. (2022). Gender and geographical disparity in editorial boards of journals in psychology and neuroscience. Nature Neuroscience 25, 272-279.

Ross MB, et al. (2022). Women are credited less in science than men. Nature 608, 135-145.

Society TP (2013). Women in Physiology. The Physiological Society, London, UK.

Tansey T (2015). Women and the early Journal of Physiology. The Journal of Physiology 593, 347-350.

Tarnopolsky MA and Saris WH (2001). Evaluation of gender differences in physiology: an introduction. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care 4, 489-492.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs PD (2022). World Population Prospects 2022: Summary of Results. United Nations Educational SaCO (2022). UNESCO Science Report: towards 2030, pp. 1-794, Luxembourg.