Physiology News Magazine

Nachrichten aus Tübingen:

Joint scientific meeting of the German, British and Scandinavian Physiological Societies, Tübingen, Germany, March 15th-19th 2002

Features

Nachrichten aus Tübingen:

Joint scientific meeting of the German, British and Scandinavian Physiological Societies, Tübingen, Germany, March 15th-19th 2002

Features

Austin Elliott

University of Manchester

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.47.8

Welcome to Tübingen

Tübingen is a delightful medieval city. Historic buildings, cobbled pedestrian streets, a hilltop castle, an ancient University, a market square, pavement cafes. What more could you ask for a Spring scientific meeting? Only good weather – and the 200 or so British physiologists who made the trip to Tübingen got that too. Despite dire warnings of icy winds or even snow – “Take your warmest jacket” said one German friend – the weather defied the gloomy predictions, with sunny skies and temperatures of 18°C plus throughout the meeting.

Not IUPS but EUPS?

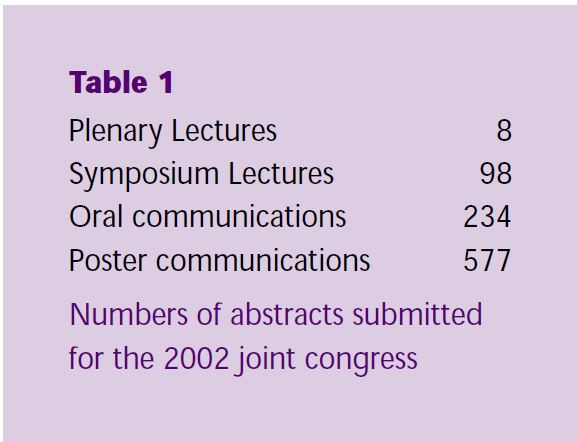

The Deutsche Physiologische Gesellschaft (DPG) only holds one scientific meeting a year, and this was it, combined for this year with both the Physiological Society and with the Scandinavian Physiological Society, and supported by the Federation of European Physiological Societies (FEPS). The single annual meeting meant a large turnout of German physiologists, so the total number of participants was nearly 1300, with over 800 communications (see Table 1). The international character of the meeting meant – luckily for the UK participants – that the meeting language was English. I always feel slightly shamed as a Brit hearing delegate after delegate from other countries give presentations in near-flawless English, but there is no denying it makes conferencing in Europe easy work for us monolingual English speakers.

The large scale of the Tübingen meeting lent it the air of a sort of mini-IUPS (EUPS, anyone?), complete with a very superior trade exhibition, nifty conference bags and a thick abstract book. The poster sessions in particular were mammoth undertakings, with a couple of hundred posters on display simultaneously on Saturday, Sunday and Monday. This did mean a fearsome crush, since the space available for poster display was pretty restricted. However, the free food and drink (non-alcoholic, since you ask) at the poster sessions helped keep us fully-fuelled.

Food Glorious Food

The catering was, in fact, one of the memorable features of the joint congress. I am not referring here so much to the formal dinner (of which more later), as to the drinks and nibbles available free throughout the meeting, morning, lunchtime and afternoon. Apart from never-ending supplies of first-rate coffee, there were trays of the sort of sweet bakery products for which Germany is famous, as well as pizza, quiche, Bratwurst and delicious hot pork rolls. The provision, and re-provisioning, of all this was extremely efficient. A measure of how seriously the organisers were taking the catering was that on occasion Florian Lang could be seen himself doing the rounds carrying a tray of pastries.

One feature of the meeting I particularly liked was the provision adjacent to the free coffee service of a large number of benches and tables where delegates could sit, drink coffee, catch up and discuss. Would it be too fanciful to catch an air of the coffee-house culture of old Vienna in this? Even more splendidly, each table was equipped with a tray of free pastries (note to self: must cut down on pastries). I was struck by the fact that a tray-load would sometimes sit for hours without anyone eating a single item. I suspect that, at a UK Physiological Society meeting, a table-full of goodies of this kind would have lasted precisely 30 seconds before being devoured by a locust-like horde of half-starved and hungover Ph.D students.

Overall, I felt the “in-meeting coffee-house” style of refreshment was vastly superior to the sort of 30 minute- long scrum-down for stewed tea that sometimes characterises our UK meetings. I think we could learn something from the DPG here. Of course, it must be admitted that the DPG charges each of its members a 50 Euro fee to attend the annual meeting, which probably explains the greater air of comfort/ luxury compared to our “home” Physiological Society meetings. But it might be worth considering a similar small charge – say £ 10 or £ 20 – for at least the bigger Society meetings in the UK.

Size isn’t everything

Big meetings have a lot to be said for them in terms of well-attended scientific sessions (and conversely, and more importantly, no really poorly-attended sessions). They also give all physiologists the chance to find just the right session for their paper or poster. However, there are other advantages apart from just “critical mass”. It will clearly be easier to attract sponsorship and recruit trade-show exhibitors if the sponsors/exhibitors know this is the one time in the year when all the members of a scientific society – their potential customers – will be present, and that there will be 1000+ of them. One meeting a year also means that virtually every graduate student and postdoc hopefully has something new to present. Against this one could argue, with some justification, that it is harder to make contacts than at a small meeting with, say, a couple of hundred participants. This is, of course, why big international meetings tend to spawn satellite Symposia. Another issue is that, if everyone in your lab has their own poster at a meeting, you can all end up grouped together in a single poster session, which can leave your corner of the poster hall feeling uncomfortably like just another lab meeting.

A favourite poster

Because the meeting spanned the whole of physiology, there was a (sometimes rather overwhelming) variety of science on offer, from hard-core molecular biology to hard-core human physiology. Talking of which…

“Favourite” might be the wrong word, but among the most eye-catching (eye-watering?) things I saw were two posters in the human neurophysiology session from the surgeons and radiologists of Tübingen University. Both posters employed the fashionable technique of functional magnetic resonance imaging to identify areas of brain activity during different tasks. The first poster dealt with areas of the brain activated during voluntary contraction of the human external anal sphincter. I am sure you don’t need me to tell you where the balloon device (which was helpfully illustrated by a photograph) was placed. In fact, the placement of a balloon device was common to this communication and the other one from the same group of authors, which dealt with the brain response to anal sensory stimulation (sic).

I was left musing that the main methodological difference between the two papers could be summarised as being that, in the second paper, the subject was simply required to brace him- (or her) self, rather than having to clench on command.

Dessert after Dinner – Hölderlin, Rachmaninoff or Satie?

The DPG, like the Physiological Society, has its own unusual traditions. The most striking of these was revealed at the conference dinner. There were no speeches, or at least only very brief ones. Instead, however, there was an after-dinner musical interlude, not to mention some poetry reciting. The special feature of this event, an old tradition of the DPG, was that the performers were all congress participants. The musical performances were of an amazingly high standard, especially given the stress involved in playing in front of several hundred of your peers, including people you might have to face in a Ph.D. defence/viva. I am not sure it would work at a UK meeting, though. Somehow I find it hard to see several hundred “well-watered” UK physiologists sitting quietly after dinner for a recitation of poetry. Off-colour limericks, maybe.

Although almost all the performers were from German labs, the Physiological Society was not totally unrepresented, since Stuart Wilson from Dundee manfully “kept the British end up” with a rendition of one of Satie’s Gnossiennes. A measure of how seriously Stuart took his representative responsibilities was that he (even more manfully) refrained from taking any alcoholic drink prior to his performance. However, I can report that he made up for this afterwards.

Vive la difference – but is there one?

Apart from the musical and literary recitals at the dinner, and the free food, there was no obvious difference between the conduct of the meeting and of the home Physiological Society meetings we are all familiar with. A scientific session is a scientific session is a scientific session, I guess. Somehow, though, German scientists seem more polite than their English counterparts. Thus I did not see a single serious disagreement during the questions after talks, and the one time a debate seemed likely to break out the Chairman rapidly closed the session! Perhaps it is too fanciful, but I had the impression that a public disagreement – even about the science – would have been regarded as a touch inappropriate. Of course, older members of the Physiological Society can sometimes be heard opining that the questioning after communications at home meetings nowadays is “not what it was” or has “gone soft”, so perhaps the Germans are just a little bit ahead of us.

In summary, we owe a tremendous vote of thanks to the organisers of the joint congress, and particularly to Florian Lang and the local Tübingen organising committee, who had obviously worked like crazy to get such a huge show on the road. They put on a splendid meeting, and one which leads me to think that “de facto pan-European” joint meetings of this kind ought to become a regular feature of the European physiology calendar.

TÜBINGEN’S SCIENTIFIC AND INTELLECTUAL HISTORY

The presence of the university, founded in 1477, has given Tübingen a rich intellectual history, and a number of significant scientific discoveries were made in the city. The early physiologists of the University worked in the unusual setting of the Tübingen castle. The castle, sited high on a hill overlooking the river Neckar, passed to the University early in the 19th century, with the kitchens becoming the University’s chemistry laboratory. Felix Hoppe-Seyler, one of the fathers of German biochemistry was Professor here in the mid-19th century. Hoppe-Seyler, who did important work on the chemistry and optical properties of haemoglobin, was an early scientific European; he was known for the international character of his laboratory, which contained both German and non-German speakers and had links with laboratories in France and the UK. Hoppe-Seyler left Tübingen for Strasbourg in 1872, and later founded the Journal of Biochemistry which still bears his name (Biological Chemistry Hoppe-Seyler, ISI Impact Factor 2.98).

The most famous discovery made in the castle labs was made by one of Hoppe- Seyler’s students, the Swiss scientist Friedrich Miescher. In 1868, Miescher succeeded in isolating cell nuclei and detected in them a phosphorus- containing substance that he named “Nuklein” (below).

Miescher separated his “Nuklein” into an acidic substance and a protein-containing basic substance. The acidic substance he had isolated was a nucleic acid – DNA – while the basic protein fraction consisted of the histones which package DNA. Later Miescher also isolated “Nuklein” from the heads of trout sperm from the River Rhine. Although Miescher is remembered in the names of several scientific institutes in his native Switzerland, his discovery of DNA – more than 80 years before Crick and Watson solved its structure – is not as widely known as it might be.

Incidentally, scientists in those days had to have strong stomachs. The starting material for Miescher’s preparation of “Nuklein” was the pus from discarded surgical bandages. This pus contained many neutrophils and macrophages, from whose nuclei the DNA was derived.

Tübingen also has a rich non-scientific cultural history. Goethe wrote his earliest works here, and was also particularly renowned for seeking “inspiration” in the local bars (see below; note kotzen = vb. to vomit).

Another latterly famous inhabitant of the town was the philosopher Hegel (dialectics), who shared a room at the Tübingen Seminary with the poet Hölderlin in the early 19th century. Hermann Hesse, the Nobel Prize-winning author of Siddharta and Steppenwolf, trained as an antiquarian bookseller at the Hechenhauer bookshop, which is still in the same building in the Holzmarkt (see below).