Physiology News Magazine

Oh the places you’ll go: my postdoc in the USA

Membership

Oh the places you’ll go: my postdoc in the USA

Membership

Mary Morrell

National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, and NIHR Respiratory Disease Biomedical Research Unit at the Royal Brompton and Harefield NHS Foundation Trust and Imperial College London

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.103.38

This year The Physiological Society and the American Physiological Society are hosting Physiology 2016 in Dublin on the 29–31 July 2016. By coincidence, this year also happens to mark 20 years since I did my Post Doc at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, USA. I have been asked how spending time in the USA has influenced my academic career; here are some of my thoughts…

|

|

National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, and NIHR Respiratory Disease Biomedical Research Unit at the Royal Brompton and Harefield NHS Foundation Trust and Imperial College London |

Got your PhD? Do you need a BTA?

My PhD studies were focused on the control of breathing during sleep, and in particular the mechanisms that led to respiratory instability. My supervisor was Professor Abe Guz, a physician and great man (Morrell, 2014). He believed that clinical observation and careful data collection were the key to good physiology research. It is hard to think now that this was before the days of computers with vast storage capacity, MRI was not readily available, and there was no internet. Maybe this was why my colleagues and I found ourselves visiting hospital wards in the middle of the night to study patients with Lateral Medullary Syndrome. These patients had localised unilateral brain stem lesions, and we wanted to understand how breathing was controlled by the bulbar spinal pathway (asleep), compared to the cortical spinal pathway (awake). These were my first research studies and they felt very difficult. What I learned in those early painstaking hours is that ‘it’s all about the data’.

Later, when I moved to America, the ability to set-up physiological studies and collect high quality data was a huge advantage. We found that the overseas Fellows often had a greater ability to set-up the equipment needed for their studies. This may have been because North America PhD students typically spend the first two years of their PhD programme studying, rather than in the lab. My experimental skills were not something I had appreciated before I went to the USA, and they are something I now try to pass on to the Fellows that train in my lab.

My early PhD studies brought me into contact with a concept named the Hypocapnic Apnoeic Threshold. This notion was first tested by Professor Dempsey and his team at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and refers to a critical threshold above which PaCO2 must rise to maintain stable breathing during sleep. So imagine my nerves and excitement when discussions of where I should Post Doc focussed on Madison.

I went to Madison Wisconsin in 1994, with great thanks to Professor Dempsey who offered me a Post Doctoral Fellowship, and The Wellcome Trust who awarded me an International Prize Travelling Fellowship. This was a three year grant, with two years in the USA, and one year back in the UK. The importance of this funding strategy is highlighted by the fact that the two previous PhD students from our sleep laboratory both went to North America, because back then in our group we got our PhD, and then we got our BTA (Been To America); however, neither came back. The Wellcome were, in my view, very wise to offer the year funding upon return to the UK; it gave me time to develop my career in London, and without it I know I would have gone back to the USA.

What did I get out of doing a Post Doc in the States?

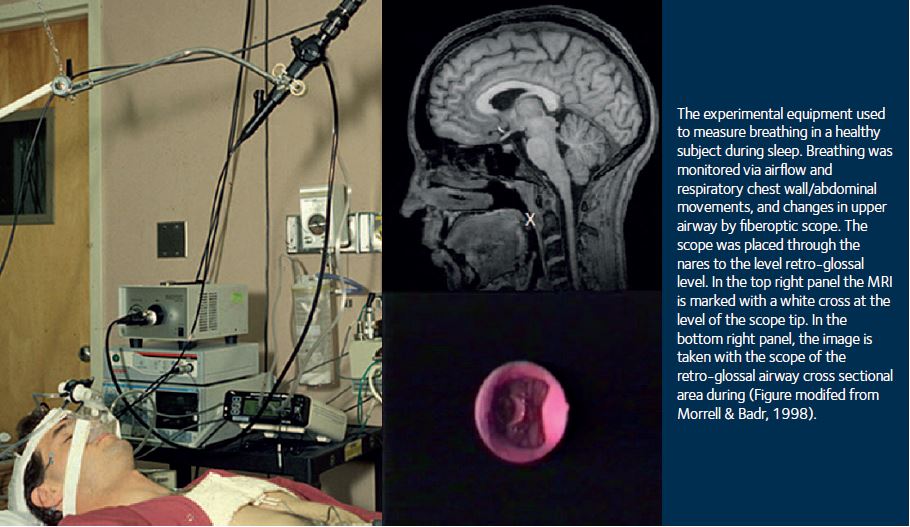

The main thing I got from the USA was the confidence to debate my science. Looking back, I think this was especially important for me. I was immersed in my field of respiratory-sleep disorders, working with world leaders. I formed my own ideas, defended hypotheses, discussed protocols and explained my data interpretation. Lab meetings started at 3:00pm on a Friday afternoon and frequently went on for hours – so many times I was told to ‘speak–up’ and eventually, slowly I did. I lost my British reserve; I embraced the American can-do attitude, and grasped new opportunities. My scientific vision became international. I was right at the edge of what was known in my field, working with those who were shaping what we know today. In particular, my project was focused on the effects of sleep on the pharyngeal airway. We developed the technology to monitor the upper airway in real time during sleep using a fibre-optic scope (Fig 1). These studies revealed airway collapsed during both inspiration and expiration (Morrell et al., 1998; Morrell & Badr, 1998) and the findings were later used to build the algorithms in machines that support the breathing of patients with sleep-related breathing disorders (autotitrating positive airway pressure).

My USA experience changed my career. It was an amazing in so many ways, and it was also a very productive; the lab was literally a research factory and I wrote many papers. However, more than this I developed an international network of colleagues and friends that have remained close ever since; we still meet up at meetings. It maybe that the impact of my time in the USA was greater back then because email had only just become available, and information was not as freely available as it is now. However, all I can say is that for me doing a Post Doc in the USA was life changing. I cannot say what would have happened if I had not gone, that’s an experiment I cannot do.

Why did I come back to the UK?

I came back for both personal and professional reasons. I am English and I missed the quirky English culture that is very different to the Mid-West. I also wanted to (rather naively) set-up a comparable sleep lab in London. By the time I returned my supervisor had retired, and I thought that in a city as big as London it was important that someone should promote sleep health.

On my return, I based my research at the Royal Brompton Hospital; I was awarded a Wellcome Trust Career Development Fellowship, and I started another journey. My clinical colleagues and I initially carried out physiological studies that highlighted the age-related changes in breathing during sleep, and their cardiovascular and neural impact. This research has now translated into to Randomised Controlled Treatment Trials in people with respiratory sleep disorders (McMillan et al., 2014; Quinnell et al., 2014) and the formation of a network of respiratory-sleep labs across the UK that collaborate together to carry out sleep research.

Spending time in North American does not mean that it has all been highs, there have been some dips. However, when these have occurred my links with the USA have enabled me to seek advice and support. When I returned to the UK, I chose to maintain my USA connections by serving on the Board of Trustees of the American Thoracic Society, and I was the first non-North American to be Chair of the ATS Sleep and Neurobiology Assembly. I have found that my international network invaluable, in so many ways at all stages of my career – maybe because the sleep field is small we all know each other and (mostly) get on very well (Fig 2).

And would you go back?

This is the question I have been asked many times – and I have had two very serious amazing offers. Both times I almost went; such is the draw for me of working in a system that is (still) better funded for physiology than the UK (despite recent cuts to NIH funding). However, in the end, my science is about making a difference, and for me that is with people in the UK. There are many things do well in the UK, and one is education and another is innovation. Education in the UK is, relatively speaking, widely available and I have benefited so much from this in my life. Working in the UK allows me to give some of this education and freedom back to others.

The UK is a country full of people with imagination and new ideas – it is exciting and energising to live and work in this environment. I am lucky enough to work at an excellent university in one of the most amazing cities in the world. America’s gene pool is one of pioneers, and the courage to discover new lands, and this is great…but London is one of the most culturally diverse cities in the world. You can choose to eat food from every nationality, and on the bus hear people speaking many different languages. We have a health care that is still free at the point of delivery, and our gun laws are safer – so here I am 20 years later. My aim has always been to make a difference, and I will always be grateful for my time in the USA and the difference it made to me and my science.

Acknowledgements

This article is dedicated to all my colleagues and friends on both sides of the Atlantic with whom I have shared my research journey. To those at Imperial College London, Royal Brompton Hospital, and the University of Wisconsin-Madison it has been a privilege to work with you.