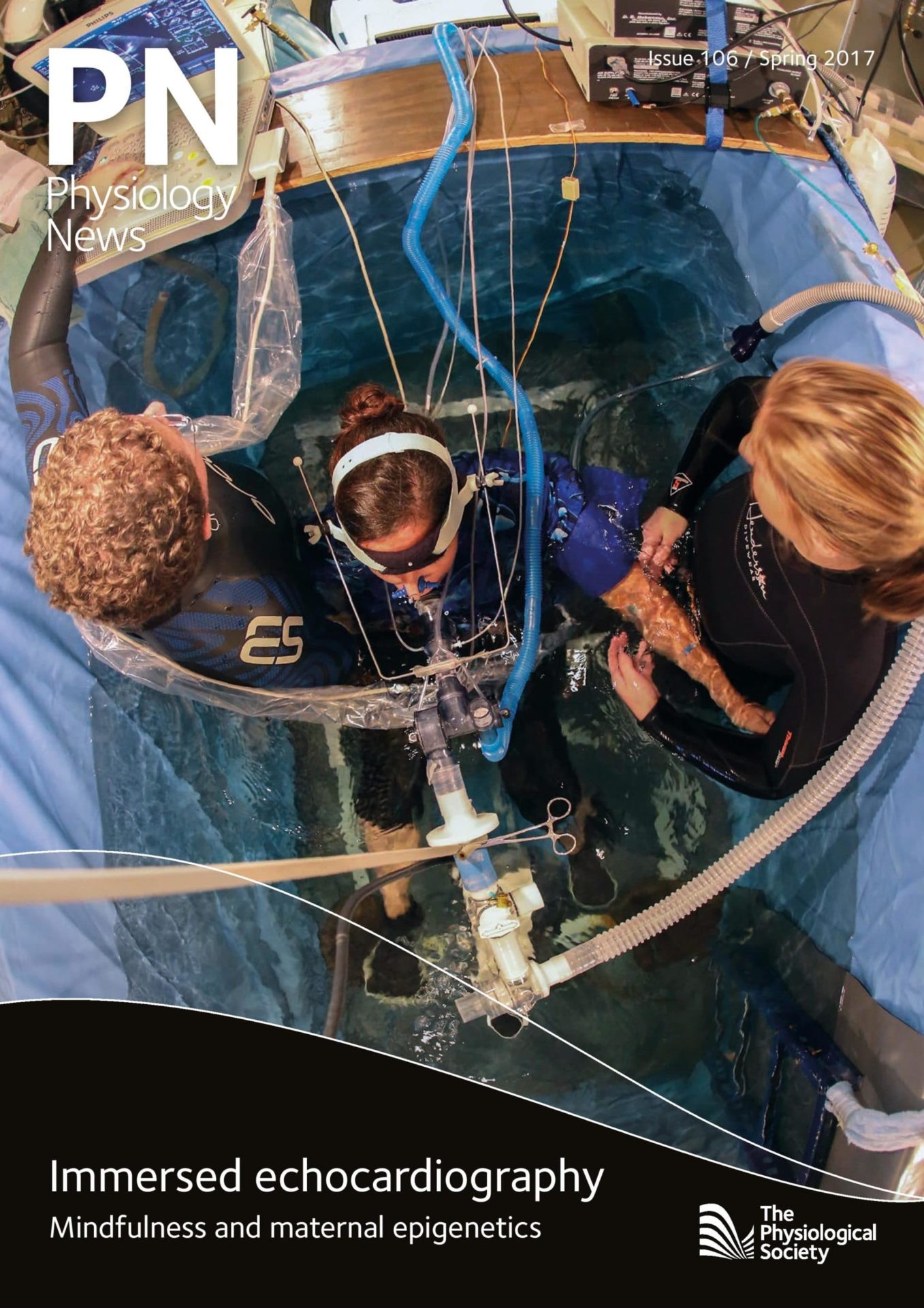

Physiology News Magazine

Personal reflections on the process of obtaining a PhD

Membership

Personal reflections on the process of obtaining a PhD

Membership

Ole H Petersen

School of Biosciences, Cardiff University, Wales, UK

A former president of The Society explains how he himself never obtained a PhD (he has an MD instead) but had a major role in initiating the lengthening of the period for which grants are available.

I may not be fully qualified to write about the PhD, as I don’t myself have one, but shall nevertheless attempt to do so! In fact, I never even had a supervisor! I started my research in 1965, when still an undergraduate (clinical) student in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Copenhagen. Having received good grades in my basic science examinations, I – like many others – was hired as an Instructor in Physiology to teach students just a few years younger than myself. The University had to operate in this way because there was insufficient staff to deal with the large numbers of students ‘invading’ the University at that time. This was also a somewhat chaotic period for the Department of Physiology with an old Chairman, who barely recognised even the senior members of staff!

My own doctoral research

It was therefore relatively easy for me to take over an empty laboratory, find unused equipment and start experimental work on the electrophysiology of salivary glands. During my years as a clinical student, I actually spent much more of my time in the Department of Physiology than in the hospital and published quite a few papers in what was then Acta Physiol Scand. After my final clinical examinations, I was immediately appointed as a Lecturer in the Physiology Department and started thinking about my doctoral thesis.

At that time, in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Copenhagen, there was only one ‘doctoral option’, namely Dr. Med. (Doctor of Medicine). This was an unsupervised degree that could be taken at any time. Most people wrote a substantial review article (book) based on a series of their own original papers. These were then submitted to the Faculty and after a very long period (typically about one year!), one would be told whether the thesis had been accepted (or rejected) for public defence. If successful, a date would be set for the public defence, where the candidate would have to answer questions from two official opponents who would criticise the thesis (typically in front of a substantial audience including all departmental staff and often staff from adjacent departments as well as family and friends). The Dean of the Faculty would preside. The Review Article had to be published as a book and had to be available for purchase in the University bookshop a couple of weeks before the defences and anyone could act as an unofficial opponent in addition to the two official ones. After the public occasion the Dean and the two official opponents would meet to decide whether the defence had been acceptable.

Thesis defence

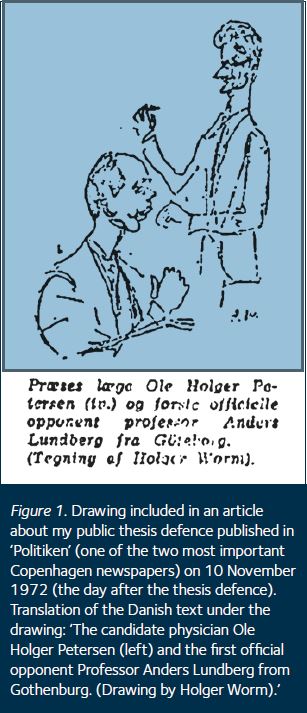

For me the public defence was a particularly ‘dangerous’ occasion, because the key element of my thesis (based on three single-author original articles published in J Physiol in 1970 and 1971) demolished the conclusions from a series of papers by my first official opponent (Fig. 1), Anders Lundberg (Professor of Physiology at the University of Gothenburg), on the electrophysiology of salivary glands, which had been published in Nature, Acta Physiol Scand and Physiol Rev in the late 1950s. To my surprise and relief, the defence went reasonably well, and Anders Lundberg gracefully acknowledged that he had been wrong. I was 29 when my Dr. Med. degree was awarded, which may seem late from a UK perspective, but was actually seen as very early at that time in Denmark (most colleagues obtained the degree in their late 30s or 40s). The public defence of a Dr. Med. thesis was, in those days, regarded as sufficiently interesting for the general public to merit a quite detailed description in the major Copenhagen newspapers, including drawings of the candidate and the most important official opponent (Fig. 1). Whatever the merits or demerits of this system, it certainly gave prominence to the scientific doctorate.

My experience as a PhD supervisor

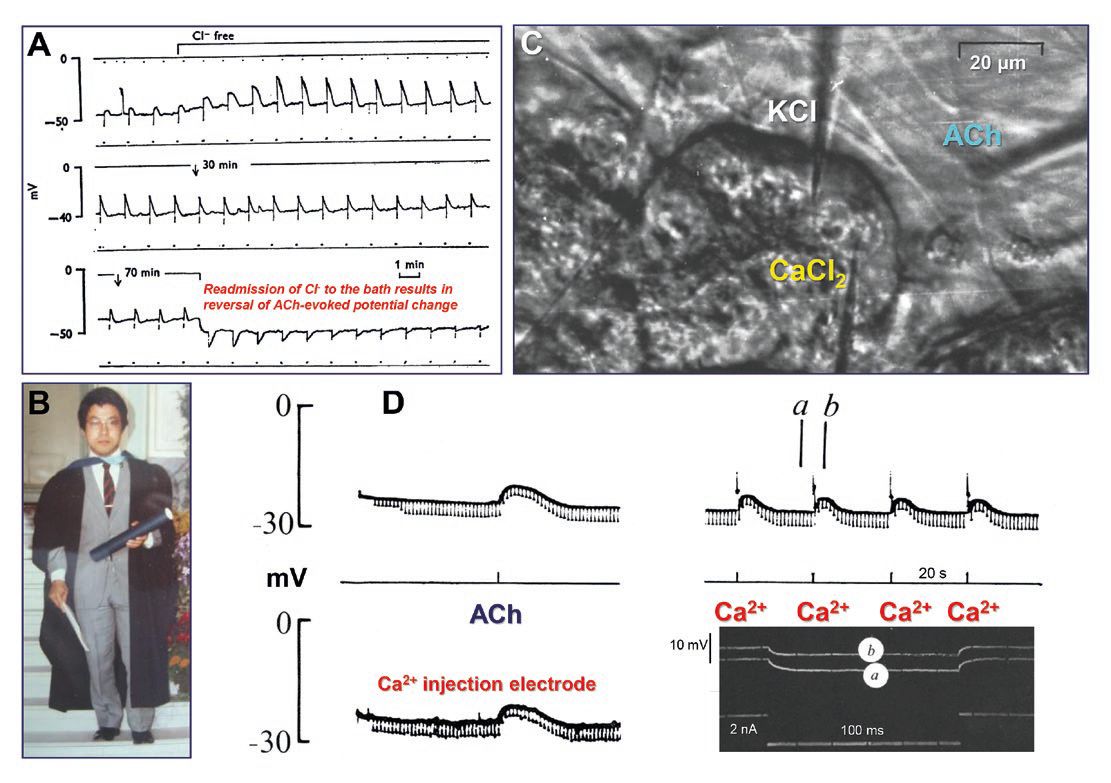

My first experience of supervising a PhD student happened after I had, just a few years later, been appointed Symers Professor and Head of Physiology at the University of Dundee. My first PhD student, Noriyuki Iwatsuki (Fig. 2), was truly exceptional. As acknowledged in the preface to my Physiological Society Monograph, The Electrophysiology of Gland Cells, published in 1980, Noriyuki’s data dominated the book. His PhD output of original papers (1976-1980) was astonishing, consisting of no less than six full papers in J Physiol, three in Nature, three in Pflügers Arch and one each in J Cell Biol and J Clin Invest. More importantly, he made some key discoveries. Fig. 2 shows results from what I consider to be his two most significant papers (Iwatsuki & Petersen, 1977a,b) in which he demonstrated that acetylcholine evokes a marked increase in the Cl– conductance of the pancreatic acinar plasma membrane and further showed that this was mediated by intracellular Ca2+.

These results have stood the test of time, but of course with more detail emerging in the better-known papers based on the patch clamp experiments conducted in the 1980s and 1990s. Noriyuki was an immensely confident experimentalist, so it was no surprise to me that his live demonstration, at the 1978 PhySoc meeting in Dundee (Iwatsuki, 1978), of gap junctional communication between neighbouring pancreatic acinar cells was completely successful, as testified in the Meeting Secretary’s minutes. It may not be particularly useful to be nostalgic about the ‘good old days’, but it is undeniable that the loss of regular opportunities to make live demonstrations of new techniques and to give short talks at PhySoc meetings has removed a very valuable element of PhD education for physiologists. It was an extraordinary piece of luck for me to have had such an able and enthusiastic person as Noriyuki as my first PhD student, and it certainly set the bar very high, possibly too high, for his successors.

Move to Liverpool and the introduction of 4-year PhD support

I became Rod Gregory’s successor as George Holt Professor of Physiology at the University of Liverpool in 1981 and held this chair for 28 years until I succeeded Sir Martin Evans as Director of the School of Biosciences at Cardiff University early in 2010. In my Liverpool period, I had many PhD students but, in spite of significant research successes, it was in general not easy, in the 1980s, to attract the best PhD students to Liverpool, although there were of course some outstanding exceptions. In my almost daily conversations about departmental matters with Graham Dockray in this period, we often returned to the PhD theme. We were not convinced that the standard 3-year PhD training was optimal. Too often it seemed that PhD students were just used as highly specialised technicians who were simply told each day exactly what they should do, without having much intellectual ownership of their own project. We felt that a 4-year course, in which the first year would mainly consist of lab rotations, might be a better option. In this way, the students could become acquainted with what was on offer in the department and would be able to make informed decisions about their choice of host lab and supervisor. Hopefully, this would also enable them to have a more creative role in structuring their own PhD project.

At that time the Wellcome Trust (WT) only funded individual 3-year PhD studentships, as did the Research Councils, so we approached the WT and had several discussions with the Trust, which led to a proposal for a 4-year PhD programme along the lines just described. However, the WT did not appear to take much notice of our proposal, and we had the impression that it had been shelved for good. Nevertheless, several years later and, I believe, mainly thanks to the efforts of Julian Jack, our proposal was somehow re-discovered and Bob Burgoyne, Graham Dockray, David Eisner and I were asked to provide an up-dated proposal, which was eventually approved and funded. In 2015, we could celebrate the 20th anniversary of the actual start of the programme (Fig. 3). The Liverpool WT 4-year PhD programme in Cellular and Molecular Physiology became the very first such PhD programme supported by the WT, but was soon followed by many other similar programmes throughout the UK. Within a surprisingly short time this approach to PhD training became popular, and there are currently 32 WT programmes of this type operating throughout the UK in various branches of the Life Sciences.

As soon as the WT programme started in Liverpool, we noticed the high quality of the students and the particularly high level of motivation for their project work. Having selected their own projects and supervisors, based on direct experience and interactions with potential labs and their PIs, the students had a great start to their PhD work and, generally, a stronger feeling of intellectual co-ownership than had been the case for their predecessors on 3-year programmes. We also noticed that the students often imported techniques from one lab into another because they, during the initial rotation year, had made valuable contacts with labs they had not finally selected for their main PhD project. In some outstanding cases, students generated entirely new projects based on combining expertise from two different labs.

International aspects

Science is international, and the UK University System has always welcomed PhD students from other countries. We can only hope that this will continue in an era where immigration control seems to have become the most important policy goal! After my arrival at Cardiff University, I was keen to expand our international PhD programme, and sometime after a visit to Guangzhou in 2011 (Fig. 4) the first PhD student from Jinan University arrived. One uncomfortable, but apparently widespread, ‘rule’ in China is that a successful PhD thesis must be based on publications in journals with an Impact Factor (IF) above 5. This is of course nonsensical as there is no relationship between the quality of an individual article published in a particular journal and the average number of citations, even within a ridiculously short time frame, to papers in that journal. In fact, the number of citations, even to an individual article, cannot be regarded as a measure of quality, but just indicates interest in the work and, to a large extent, depends on the size of the particular research field. Nevertheless, one cannot jeopardise the future career of an individual for the sake of a general principle, and we did solve this ‘problem’ in the case of our first student from Jinan University (Peng et al., 2016). However, it is undoubtedly necessary – again and again – to explain (even in our own Universities!) the general damage to the reliability and reproducibility of our science which is caused by relying on the IF as a measure of quality. In this respect, I think the unreasonably maligned REF actually gives a good example by explicitly forbidding the use of IF as a method of evaluation.

Conclusions

Overall, I believe that the now popular 4-year PhD courses present an improvement on the previous 3-year model, although there will always be students who know exactly what they want to do immediately after their BSc Hons degree without having to go through an initial lab rotation year and, therefore, we need a degree of flexibility. The principal problem we face in today’s increasingly over-audited and over-regimented University World, with massive teaching loads, is lack of time to guide our PhD students. No amount of auditing and tick-boxing can compensate for intensive in-depth discussions! We may also want to rethink the rather low-key way in which we are now able to acknowledge the accomplishments of our PhD students, which has become exacerbated by the loss of opportunities for demonstrating and speaking at PhySoc meetings. The final PhD examination in the UK, which is really a rather private discussion with PhD examiners, is in stark contrast to the rather more festive conclusion to doctoral studies (Fig. 1), which can still be experienced in some other countries, as I found out recently when acting as official opponent at a public thesis defence at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm.

References

Iwatsuki N (1978). Direct demonstration of cell-to-cell communication in mammalian pancreatic acini: transfer of fluorescent probe molecules. J Physiol 285, P1-P2

Iwatsuki N & Petersen OH (1977). Pancreatic acinar cells: localization of acetylcholine receptors and the importance of chloride and calcium for acetylcholine-evoked depolarization. J Physiol 269, 723-733

Iwatsuki, N. & Petersen, O.H. (1977b). Acetylcholine-like effects of intracellular calcium application in pancreatic acinar cells. Nature 268, 147-149

Peng S et al., (2016). Calcium and adenosine triphosphate control of cellular pathology: asparaginase-induced pancreatitis elicited via protease-activated receptor 2. Phil Trans R Soc B 371, 20150423