Physiology News Magazine

Peter Mark Roget:

Polymath extraordinaire

Features

Peter Mark Roget:

Polymath extraordinaire

Features

Hana Beswick-Jones

Amy J Hopper

Dr Angus M Brown

School of Life Sciences, University of

Nottingham, UK

The development of mental illness can condemn the sufferer to a life of solitude, frustration, and thwarted ambitions. Even those who manage to cope with their affliction tend to suffer prolonged periods of inactivity and hopelessness, characterised by reduced productivity. Peter Mark Roget, however, author of the eponymous Thesaurus, was able to channel his mental illness to constructive ends, his inquisitive nature directed to searching for a sense of order, which was evident in his diverse occupations as physician, physiologist, mathematician, and author. As such Roget can be considered a positive role model, an example of an individual who prevailed in the face of the considerable challenges that accompany a diagnosis of mental illness. His best-known work, the ubiquitous Thesaurus, changed the world, and as we celebrate 170 years since its publication, it remains an essential and treasured tool for novice and experienced writers alike.

Childhood

Early events in Roget’s life shaped his personality. Born in London on 18 January 1779, he was 6 months old when his parents, Catherine Romilly and Jean Roget, travelled to Switzerland in the vain hope of treating his father’s tuberculosis. Roget was left in the care of his maternal grandfather, Peter Romilly, a prosperous jeweller and one-time neighbour of the Mozart family during their stay in London in 1764, Romilly attending concerts given by the 8-year-old prodigy. Rogets’s father died in 1783, soon after his return from the continent, an event that had a devastating effect on his mother, who recalled her life as perfect happiness prior to her husband’s death. The mores of the day dictated young widows with limited financial means had little chance of remarrying and she was condemned to a life of widowhood. Catherine was unable to receive counsel for her grief, her solitude compounding her heartache, leading to depression and a listlessness that compelled her to move with Roget and his younger sister, Annette, several times a year. Such rootlessness instilled in Roget a sense of instability and inability to form attachments with his peers.

A teacher commented to his mother that “I am still surprised he hasn’t found a friend to enliven his activities.” Catherine’s mother had been subject to schizophrenia-like symptoms, ascribed to the early deaths of six of her children, and the family tree (Fig.1) illustrates how mental illness (diagnosed retrospectively from contemporary accounts of symptoms and behaviour) haunted the family through four generations. Catherine would measure her life against her son’s achievements, becoming overbearing and interfering. The more she smothered Peter the more he recoiled and retreated, developing into a classic loner. When he was 8 years old, he began compiling lists, starting with “Dates of Death”, in which he noted the passing of friends and family members, a list he updated until he was 78 years old. One of Roget’s schoolteachers was a Swiss preacher, Etienne Dumont, who encouraged Roget’s fascination with words and astronomy, his interest in Roget inspiring the boy to immerse himself in these subjects. These academic pursuits would prove pivotal to Roget’s future achievements, his interest in words embracing astronomy, geometry, and algebra, with Roget considering mathematics as a pure language, which has rigid rules for describing abstract concepts (Kendall, 2008).

Psychologists assert that between the ages of 8 and 12 is when children invent paracosms, imaginary private worlds. The importance of these worlds is that they allow children to ignore the stresses and uncertainty of the real world, and instead inhabit a world of their own devising, where they feel comfortable, secure, and at ease. Children tend to sustain an interest in these paracosms their entire lives, and such was the case with Roget. He created a paracosm that involved a search for order that was achieved by cataloguing objects, his total immersion in this venture dissipating his feelings of anxiety. He proceeded to make Latin word lists, the nascent form of his Thesaurus, and this cataloguing mania continued into his adult life. The Thesaurus is an obvious example, but his physiology textbook Bridgewater Treatise Vol 5 was an enormous review of contemporary information organised according to comparative anatomy and physiology.

Medical and scientific career

In 1793, at the tender age of 14, Roget travelled to Edinburgh, accompanied by his mother and sister, to study medicine. One of his lecturers, Dugald Stewart, considered appropriate use of words paramount and the imperfections of language planted the seed for Roget to make a systematic attempt to tidy up word usage. Stewart inspired Roget to become a scholar and he passed his exams, his dissertation on classification of the laws of chemical affinity. In 1798, he travelled to Derby where he met Erasmus Darwin, Humphrey Davy and Thomas Beddoes. He moved to Clifton, Bristol, to work in the Pneumatic Institute founded by Beddoes, an eminent physician, who championed the use of gases such as oxygen, carbon dioxide and nitrous oxide to treat tuberculosis. Roget was one of the first to sample nitrous oxide as a recreational drug – it was not to his liking (Wright, 2001).

In 1800 Roget returned to London to train in anatomy. In 1802 Roget acted as guardian to the two teenage sons of a local industrialist and accompanied them on their grand tour of Europe. The timing of this trip could not have been worse as the tenuous peace between Britain and France was shattered with the failure of the Peace of Amiens, and Napoleon began imprisoning British nationals resident in France. Roget and his charges fled to Switzerland and were lucky to escape. In 1803 Roget returned to England and in 1804 took up the position of physician in Manchester at the city infirmary, where he helped found the medical school. However, Manchester, at the heart of the Industrial Revolution, was filthy, and Roget became despondent, channelling his depression into his lists. In 1806 Roget gave his first lectures on physiology. He realised there was a systematic arrangement of physiology, which he divided into four functions: mechanical, respiratory, nervous, and reproductive. In his first lecture he discussed mechanical functions, which he further divided into five subclasses: mechanical properties of cellular texture, chemical composition of cellular substance, membranous connections, provisions for the defence of the body, and muscular action (Snell, 1974).

Roget maintained his interest in physiology and in 1809 he moved to London where he lived for the rest of his life. He became an independent physician but realised a path to success lay in association with learned societies and institutions. In 1809 he was licensed by the Royal College of Physicians, joined the New Medical and Chirurgical Society of London (renamed the Royal Society of Medicine in 1907), and later became secretary of the Royal Society for 21 years. The Royal Institution appointed him Professor of Comparative Physiology in 1812, followed by appointment as the first Fullerian Professor of Physiology. Roget’s studies in physiology are too numerous to describe here, but a detailed account can be found in an excellent review (Kruger and Finger, 2013). His most famous paper was on optics, in which he described retinal after-effects as an explanation for an optical illusion created by rotating spoked wheels (Roget, 1825). His most impressive academic work was his contribution to The Bridgewater Treatises; Animal and Vegetable Physiology Considered with Reference to Natural Theology published in 1834 as Vol 5 in the series. The Treatises were sponsored by the 8th Earl of Bridgewater and devoted to illustrating the power of God. Roget used design in nature as evident from comparative anatomy as proof of the existence of God. This enormous work was 600 pages in length and categorised not only Roget’s work on areas of physiology, but also other relevant contemporary work. However, in 1846 Robert Grant, Professor of Comparative Anatomy and Zoology at the University of London, wrote a letter to The Lancet claiming Roget had plagiarised some of his ideas for the Treatise (Grant, 1846). Roget’s reputation was tarnished, with The Lancet dubbing him “a literary pilferer”. Roget retired as secretary of the Royal Society in 1847 a wounded man. He refused to apologise or concede any wrongdoing and found himself at the age of 70 with boundless energy and time on his hands.

Thesaurus

It was while in Manchester in 1805 that Roget produced his initial thesaurus, entitled Collection of English Synonyms Classified and Arranged, which contained 15,000 words. Roget was not the first to create a book of synonyms. In 1718 French monk Abbé Gabriel Girard produced one in French, his motive that he considered speech the force that held society together, and that clear thinking depended on the ability to express oneself clearly. He grouped words together that expressed common ideas and wrote a few paragraphs on the appropriate use of each synonym. There were 295 such articles. In 1776 Englishman John Trusler translated Girard’s book into English. About 30 years later Hester Piozzi published a thesaurus, which consisted of 310 articles. It was not systematic and devoid of academic rigour; Roget was unimpressed and considered it lacked cohesion, conflicting with his belief that words were crucial tools that promoted the progress of human knowledge. Roget was influenced by John Horne Tooke, who argued in his 1786 book that all words could be traced back to nouns and verbs. Tooke inspired Roget to think systematically about how to organise words in his thesaurus. Roget’s embryonic thesaurus was not published, but he used it regularly to express himself more lucidly.

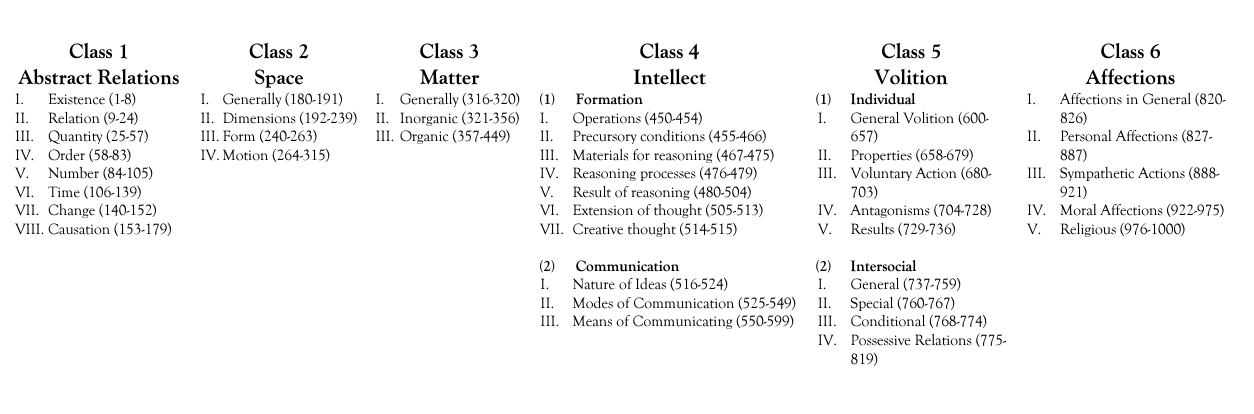

At around the time of his retirement from the Royal Society, interest in Piozzi’s work was rekindled, which acted as an incentive for Roget to update his Thesaurus, which he commenced in 1849 and published in 1852. As he stated in the preface, “I had often during the long interval found this little collection, scanty and imperfect as it was, of much use to me in literary composition, and often contemplated its extension and improvement; but a sense of the magnitude of the task, amidst a multitude of other avocations, deterred me from the attempt.” For those who are used to a thesaurus comprising solely an alphabetical index of key words and their synonyms, the Roget Thesaurus is a revelation, its classification template a model of utility. Roget devised six classes, the framework around which his Thesaurus was constructed. The first three classes encompass the external world and the last three concern the internal world (Fig.2).

- Abstract relations

- Space

- Matter

- Intellect

- Volition

- Affections

There is a logical progression from abstract concepts, through the material universe to mankind, followed by what he considered mankind’s highest achievements, morality, and religion in the class of Affections or Emotion. The brilliance and insight of his classification ensured that the layout of the Thesaurus has survived for 170 years with only minor modifications. The classification may be viewed as a tree with the six main branches (classes) further divided into smaller branches and twigs until it comprised 1,000 concepts. Roget’s view of the Thesaurus is concisely summarised in the first paragraph of the introduction to the original 1852 edition: “The idea being given, to find the word, or words, by which that idea may be most firstly and aptly expressed. For this purpose the word and phrase of the language are here classed, not according to their sound or their orthography, but strictly according to their signification“. He further claimed “there are words and phrases sufficient to satisfy the most exacting writers and the most diverse tastes.” It was only as an afterthought that Roget added an index that listed words in alphabetical order with their associated synonyms, the form of thesaurus with which most people are familiar.

The Slide Rule

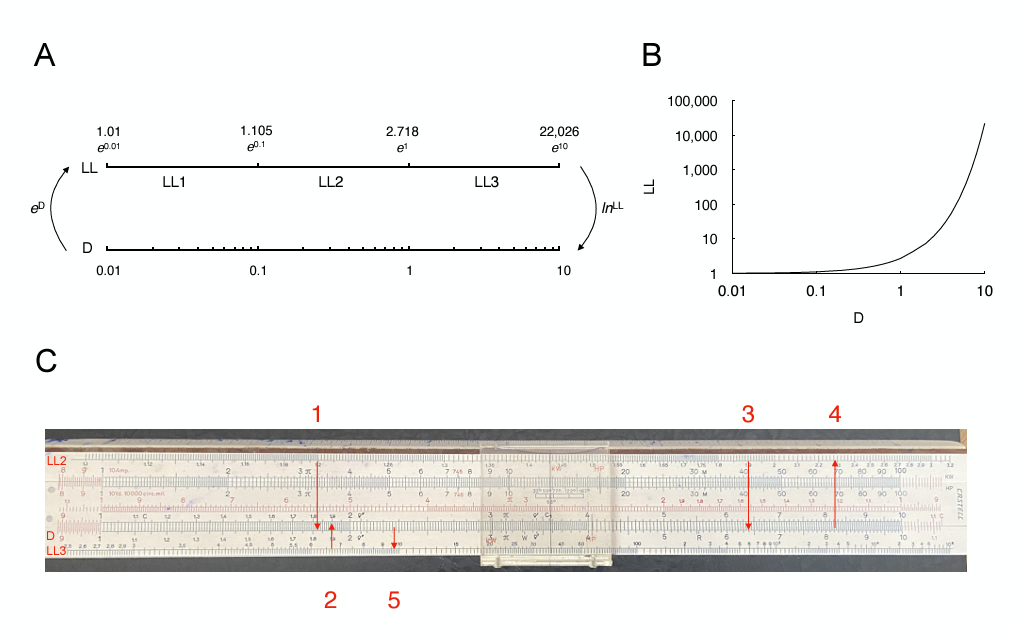

Perhaps Roget’s most unexpected achievement was in the field of mathematics, since it did not follow the ordering of objects that defined his other work. He was acquainted with William Haydn Wollaston, who invented the chemical slide rule in 1814 to aid with calculations involving chemical proportions (Gotlib, 2012). Roget worked to modify the slide rule to allow calculations of powers and roots and realised this could be achieved by applying the laws of logarithms via the development of the log log scale (Fig. 3) (Roget, 1814). This operation conformed with the intention of the logarithm’s inventor, John Napier, that multiplication was converted into addition. Roget’s insight was to logarithmically transform the factor twice as follows:

To calculate 6.71.2

take the ln of this expression

ln(6.7)1.2

Apply the 3rd law of logarithms: ln(a)b = b ln(a), thus

1.2 ln(6.7)

take the ln of this expression, apply 1st law of logarithms: ln(a x b) = ln(a) + ln(b)

ln(1.2) + ln(ln(6.7))

(Steps 1 and 2 in Fig.3C)

0.182 + ln(1.90)

(Step 3 in Fig.3C)

The power calculation becomes addition of logarithmically transformed numbers

0.182 + 0.642 = 0.824

Then carry out the inverse transformation twice, such that

e0.824 = 2.27

(Step 4 in Fig.3C)

e2.27 = 9.77

(Step 5 in Fig.3C)

Thus 6.71.2 = 9.77

This process is displayed graphically in Fig.3C. In 1814 Wollaston presented Roget’s paper on the slide rule to the Royal Society, and Roget was elected Fellow in 1815.

Later life

In 1824 Roget married Mary Hobson, producing two children, Kate (b. 1825) and John (b.1826). In 1833 Mary died, and to alleviate his depression and occupy his mind Roget commenced work on his Bridgewater Treatise. His daughter Kate began to display symptoms of mental instability in 1849, when she was 23, her erratic behaviour a source of constant worry for Roget, who resorted to isolating her from any contact with friends, presuming that his means of dealing with his illness by shutting out the world would also help her. It seemed to work, and Kate returned to her family. Although she never descended to such depths again, she remained unmarried and dedicated herself to supporting Roget’s work, caring for him in his old age. He died in 1869 at the age of 90. Although Roget periodically sank into depressions, most notably while in Manchester in 1805, after the suicide of his uncle Sir Samuel Romilly in 1818, and upon the death of his wife in 1833, he always prospered professionally.

It is interesting to note that in 1860, at the age of 81, Roget attended the famous debate on evolution at the University of Oxford, attended by Charles Darwin, whose Origin of the Species had been published the previous year. As a result of the debate the scientific community relegated God’s importance in science, an event that distressed Roget and his interest in science began to dwindle (Fig. 4).

Roget’s Thesaurus had 28 printings in his lifetime, and after his death his son John assumed editorial responsibilities, followed by Roget’s grandson Samuel, who sold the copyright in 1952. The Thesaurus has lost 10 concepts since its original publication, but the proliferation in vocabulary has dramatically increased the number of words.

In recognition of Roget’s paracosm, we note an impressive list of his friends and associates: Erasmus Darwin, Michael Faraday, Humphrey Davy, James Watt, Charles Dickens, Edward Jenner, William Herschel, Thomas Young, Thomas Huxley, Charles Babbage.

References

Gotlib LJ (2012). Chemical slide rules: Their history and use. Journal of the Oughtred Societ. 21(2), 8-15.

Grant RE (1846). Dr Roget’s Bridgewater Treatise (Professor Grant’s reply to Dr Roget). The Lancet 47 (1181), 445-446.

Kendall JW (2008). The Man Who Made Lists. Putnam’s & Sons New York

Kruger L, Finger S (2013). Peter Mark Roget: physician, scientist, systematist; his thesaurus and his impact on 19th-century neuroscience. Progress in Brain Research 205, 173- 195. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24290265

Roget P (1815). Description of a new instrument for performing mechanically the involution and evolution of numbers. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 105, 9-28.

Roget P (1825). Explanation of an optical deception in the appearance of the spokes of a wheel seen through vertical apertures Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 65, 131-141.

Snell WA (1974). Peter Mark Roget, FRCP. J Roy Coll Phycns Lond 8 (3), 276-282.

Wright AJ (2001). Peter Mark Roget and the Bristol nitroux oxide experiments, 1799-1800. Bulletin of Anesthesia History 19, 16-19. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20503749