Physiology News Magazine

Physiology in the extreme

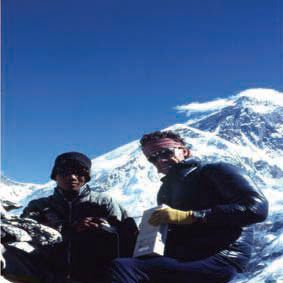

Thelma Lovick talked to another intrepid physiologist who takes his science into the extreme. Below, John Coote, Professor Emeritus in the Division of Neuroscience at the University of Birmingham, shares some of his experiences of doing physiology in the extreme environment encountered at high altitude

Features

Physiology in the extreme

Thelma Lovick talked to another intrepid physiologist who takes his science into the extreme. Below, John Coote, Professor Emeritus in the Division of Neuroscience at the University of Birmingham, shares some of his experiences of doing physiology in the extreme environment encountered at high altitude

Features

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.62.16

Thelma Lovick (TL) I understand you’ve worked in the Peruvian Andes as well as in Chile, the Italian and Swiss Alps, Karakoram in N Pakistan and in Nepal in the Everest region and Himulchuli. How did you get started on all this?

John Coote (JC) Well as you probably know, I used to be quite a keen climber. When I first went to East Africa to climb the north face of Mt Kenya, I experienced severe headaches and nausea and it took me several days to recover. Within our group, though, some weren’t affected, and I began to wonder about the reasons for this individual variability in the ability to adapt to low pO2. There are also more prosaic reasons for needing to understand our reactions to low pO2. The military is obviously very interested in ways to keep the troops in peak condition if they are flying them in over long distances to drop them into a high altitude combat zone. Skiers, too, can be badly affected by low pO2 .

TL So why do you need to take your lab to the mountain when there are perfectly good altitude labs around the world where you can live and experiment at low pO2?

JC I thought you’d ask me that! My interest is in the response of lowlanders to long periods at altitude and the best way to simulate this is to actually be there. Also, altitude chambers aren’t that comfortable to be in. And compared to the mountains the view is terrible!

TL Tell me how you set up one of these expeditions.

JC There’s months of planning involved. Inevitably, when you go to remote areas with poor access, you have to take your whole lab in a portable form. You have to take spares and be prepared to be quite resourceful in terms of mending equipment in the field.

TL How do you transport all this stuff? Presumably there are no roads.

JC Well, you helicopter everything in to give you a start. Then it goes on to pack animals or on to the backs of porters. Always when going above 18,000ft you have to use local porters. In fact, portering provides quite a boost to the local economy in many areas and there are often queues of guys waiting to be selected.

TL Let’s take one of your trips to Everest. Is it really the mess we hear about?

JC I’m afraid it was, although attempts are now being made to clean it up. When I was last there, which is now 10 years ago, the route in was littered with the debris left by Westerners.

TL And are you guilty of adding to that?

JC We do our best to bring everything out with us, but I must confess there are occasionally things that fall down crevices when we’re at high altitudes.

TL Tell me about a typical day.

JC We live in tents in the snow and the day starts when one of the porters brings you hot sweet tea to get you going. Then you get out of your sleeping bag, have something to eat and set to work.

The days are very organised – everyone has a designated task and nobody is idle. We may all have to attend the medical tent to be weighed, measure body fat, heart rate, blood pressure, give saliva, blood samples, etc. If you’re doing a sleep study your electrodes for EEG, ECG and ventilation will need removing or replacing along with your Medilog recorder. In an exercise study we take along a bicycle ergometer and test people at different workloads. The bike is heavily used and takes a lot of punishment. We often have to use it outside so it’s very unpleasant if you’re the minder of the bike!

TL What about meals?

JC Lunch and tea breaks are organised by the porters and Sherpas. But you don’t eat a lot. You’re busy, it’s cold, you have no appetite and it’s actually quite hard work to make the effort to eat. The whole environment is not exactly conducive to eating and the food is mainly dried stuff. Above 18,000 ft we exist mainly on tea, porridge, chapatis, jam and reconstituted soup and stews – it’s not a great culinary experience. You need about 3000 Kcal per day, but I don’t usually have more than about 1500 Kcal so consequently I lose around a stone or more over a month.

When you stop working you just want to get into your sleeping bag to keep warm. You go back to your two-man tent once you’ve finished your work and maybe chat to your companion for a bit before the final meal of the day, or you just have a snooze. This can actually be quite worrying if the other person remains awake at this time because at altitude you go into periodic breathing and you may stop for quite long periods of time. There have been incidents when non-medical scientists have panicked because they thought their partner had died!

TL If you’re living at altitude in a hypoxic environment, presumably you are functioning at less than 100% mental capacity. How can you be sure that the science you do is actually any good?

JC Well we plan everything in detail before we go and we’re all pretty experienced scientists and highly motivated, so this helps. The organisers of the trip take diamox (a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor) and this helps quite a bit too. We have on occasions had to send people down, though, because they got so ill. Once we were in the Alps just below the Matterhorn at about 11,000 ft. We were using a mountain hut as a lab and on the second night one guy, an experienced mountaineer, developed pulmonary oedema. Fortunately, we had some furosemide (a diuretic) with us. So we started him on that and then had to get him down the mountain in the dark and snow whilst collecting his copious urine output in lemonade bottles! He recovered OK, I’m pleased to say.

TL It all sounds a bit grim to me. Are there any good bits?

JC Being in such remote environments, you notice that it is absolutely pristine – stunning in fact. And this offsets the unpleasantness of the rest of the time. But it’s not everyone’s cup of tea by any means.

TL Any scary moments?

JC There have been a few. I suppose the most hazardous time was in a village in Peru when we came in the way of the Shining Path guerrillas and had to spend most of the night under the bed as the bank outside the lab was blown up and bullets started flying when the army was sent in!

Then there was the famous episode of the dodgy Russian we met in a bar in Kathmandu. We needed to move our gear to Lukla (9,400 ft) and he said he had a helicopter and could do it for us. David Paterson (University of Oxford) began negotiations and we ended up handing over a pile of cash and striking a deal to meet him at night in a remote field. We hired a Sherpa and a battered bus to get our stuff there but on the way our path was blocked by a huge pile of stones, which turned out to be a terrorist road block. We had to dismantle it stone by stone, not knowing whether we’d be killed at any moment.

Finally, after waiting nervously in this field with our kit, the helicopter arrived very low, just about skimming the mountain tops. Flights in Nepal are monitored by the military so it could land only for a short time out of radar surveillance. We bundled our stuff in and got out OK. But it was all a bit hair-raising.

TL It all sounds very British and gungho.

JC Perhaps, but nevertheless good science does get done. You have to be very determined and single-minded. Although I do have to admit that for me it’s an excuse to visit the high mountains as a break from my main lines of research. We have still published some important original observations on altitude sickness and sleep, though!

Extract from John Coote’s diary

July 12 (18,000 ft)

4.30 a.m. Wake after good night’s sleep to see it’s snowing heavily. Temp outside minus 30 degrees. I feel warm and cosy in sleeping bag. I have all my outside clothes on, 2 pr socks, woollen long-johns and salopettes, wool vest, shirt and pullover, balaclava and hood of bag pulled tight to leave small breathing hole through which 13 leads connected to Medilog recorder and Bioximeter pass.

Generator worked throughout night, no doubt thanks to Pete and Neil keeping the fuel supply going every 2 hrs. So biox worked all night. Alveolar oxygen now at 52 mmHg. It snowed all day, about 18 inches, tents completely submerged 2 collapsed. Clear some of the snow but not much else done today.

The scientific question

As we fall asleep our brain responds less to the outside world, yet it does not switch off. The sleeping, but active, brain actually requires increased amounts of oxygen compared to the resting awake brain. To supply this, blood flow increases. Studies in sleeping animals suggest that the blood flow changes are finely tuned by the arterial chemoreceptors, which are one of the few afferent inputs that maintain a strong influence on brain activity during sleep. At sea level, where the blood is fully saturated with oxygen, the blood flow increase in sleep is sufficient to supply the needs of the brain even though ventilation is slightly decreased. However, at high altitude the barometric pressure can be low enough to seriously decrease SaO2 and an alteration in oxygen delivery to the brain during sleep can severely affect brain activity. It is not surprising, therefore, that hypoxic insomnia is a common complaint amongst trekkers, skiers and mountaineers sojourning above 10,000 ft. So what are the physiological changes in visitors to high altitude and, even more interesting, how have residents at high altitude adapted? These are questions that have kept drawing me back to the mountains.

Publications arising from John Coote’s ‘holidays’ at altitude include:

Coote JH, Nicholson AN, Smith PA, Stone BM & Bradwell AR (1988). Altitude insomnia studies during an expedition to the Himalayas. Sleep 11, 354-361.

Smith PA, Coote JH, Nicholson AN & Stone BM (1989). Sleep during an alpine expedition. Aviat Space Eviron Med 59, 478481.

Coote JH, Stone BM & Tsang G (1992). Sleep of Andean high altitude natives. Eur J Appl Physiol 64, 178-181.

Coote JH, Stang G, Baker A & Stone BM (1993). Respiratory changes and structure of sleep in young high altitude dwellers in the Andes of Peru. Eur J Appl Physiol 66, 249-253.

Coote JH (1993). Sleep at high altitude. In Sleep, ed. Cooper R, pp 242-264. Chapman Hall, London.