Physiology News Magazine

Physiology in the United States of America

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times”.* The leaders of the largest physiological society in the world find physiology in the USA facing a time of great promise, but also real challenges.

Features

Physiology in the United States of America

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times”.* The leaders of the largest physiological society in the world find physiology in the USA facing a time of great promise, but also real challenges.

Features

*Charles Dickens (British novelist, 1812-1870), A Tale of Two Cities

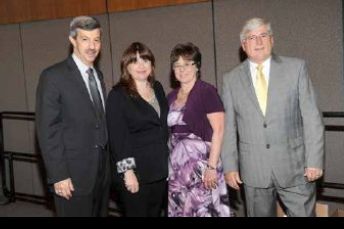

Kim Barrett

86th President (2013-2014)

Susan Barman

85th President (2012-2013)

Joey Granger

84th President (2011-2012)

The American Physiological Society

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.91.37

As the three current Presidents of the American Physiological Society, it is an honor to share some thoughts with the readership of Physiology News about the status of physiological sciences on our side of ‘the pond’ on the occasion of the upcoming IUPS meeting. We suspect that many of our concerns about the future may resonate with physiologists worldwide. And yet, there are so many opportunities also available at the present time that it is hard not to be optimistic about the pathway forward for the discipline.

Opportunities abound

Numerous developments make this an opportune time to be a scientist focused on integrative, rather than reductionist, approaches to biomedical science and an understanding of human (and animal) diseases. First, there have never been better tools available to examine cell and organ function in the setting of living animals and humans, including studies conducted in real time. In part, these tools derive from advances in imaging, but there are many others. There are numerous examples of how wholly in vitro studies may be misleading when used to predict underlying mechanisms of both disease states and normal physiology. This implies that both colleagues and funding agencies should place emphasis on the incorporation of physiological thinking in all studies that have the goal of defining such underlying mechanisms.

The post-genomic era has also seen a sharply increased emphasis on studies that take as their starting point massive datasets to elucidate and predict the function of integrated systems. Examples include the use of metabolomics approaches to understanding the consequences of complex, multi-organ disease states, such as diabetes, as well as efforts to dissect the role played by the intestinal microbiota in nutrition, digestive diseases, and obesity (Patterson et al. 2011; Yatsunenko et al. 2012). Just this month, President Obama announced a new research programme dubbed the BRAIN (Brain Research through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies) Initiative, aimed at producing dynamic maps showing how individual neurons and the brain circuits they make up function at the speed of thought (www.nih.gov/science/brain/index.htm). This initiative is hoped to shed new light on the pathogenesis and possible treatments for conditions ranging from Alzheimer’s disease and epilepsy to traumatic brain injury. Physiologists have, and will, make major contributions to these ‘big data’ projects, and we should consider how to amend our graduate curricula to ensure the next generation of our trainees can be equipped with the tools needed to participate.

Translational research has also taken centre stage in the United States as the federal government, funding agencies and the general public look for returns on investments in biomedical research. Physiology remains the cornerstone of effective medical care and thus our discipline, and our members, are well-placed to reap the benefits of this emphasis. Increasingly, basic scientists are collaborating with clinical colleagues, including in the national network of Clinical and Translational Research Institutes, to bring innovations from the lab to the clinic. There have also been programmes designed to better acquaint our physiology and other basic science trainees with pressing problems encountered in patient-care settings, such as the Med Into Grad initiative of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (www.hhmi.org/grants/institutions/medintograd.html). We have personally witnessed the personal growth and passion that develops when PhD students have the opportunity to map the goals of their thesis project to observations they make when shadowing physicians on rounds.

Finally, the American Physiological Society is in great shape as an advocate for our discipline and the next generation of physiologists. In particular, we have a robust programme of outreach and educational activities that span from kindergarten to post-docs, including our annual Physiology Understanding (PhUn) week that has reached more than 40,000 schoolchildren with activities that introduce physiological principles, and our Professional Skills Training Courses that equip our graduate students and post-docs with key career-building competencies such as writing and reviewing, networking, and interviewing skills. Further, since our last strategic plan, we have emphasized the role of our regional chapters in the wider promotion of physiology. Existing chapters have been reinvigorated and new chapters have been founded, and each stresses meetings where trainee involvement is central.

Challenges we face

Despite these myriad opportunities, there are also threats to our discipline in the United States and indeed to the biomedical enterprise in general. Particularly topical at present are the cuts to federal support for biomedical research, and especially the spectre of sequestration. It is not yet fully clear to what extent this across-the-board reduction in government spending will impact grant funding and thus the research enterprise, but early indicators are not encouraging. Scientists are reporting substantial cuts to their budgets for existing awards, and the prospect for those with applications in the pipeline are grim. We run the risk of losing a large cohort of would-be physiologists at a critical stage of their career, since they may rightfully conclude that a research career offers too many uncertainties for a well-balanced lifestyle.

The place of physiology in both medical and graduate curricula has also been evolving. Many medical and other professional schools are eschewing a curriculum that includes stand-alone courses in the basic biomedical sciences in favour of organ-based or integrated programs that stress the involvement of (for example) physicians in even pre-clinical training. While these educational models may have promising outcomes, at least based on initial experience, we run the risk that physiology will lose its identity and that physiologists will lose opportunities to contribute to professional education. At the same time, the US National Institutes of Health recently completed a taskforce report on the status of the biomedical workforce that concluded that we need to do a better job of training graduate students for a wider range of possible career outcomes than simply becoming clones of their advisors, including jobs in industry, policy and legal settings (blogs.nature.com/news/files/2012/06/draft-report-from-the-Biomedical-Research-Workforce-Working-Group.pdf). This is also to be accomplished without extending the length of graduate training. This may run the risk of further displacing physiology content from the curriculum, particularly in interdisciplinary programmes, but does have the distinct advantage of highlighting the many possible pathways that can be followed by those who develop a physiological mindset.

We also face, at least in the United States, an apparently diminishing number of domestic students equipped to deal with quantitative science. Not only does this impact classical physiological approaches, but also our ability to participate in the ‘big data’ and integrative approaches discussed above. In part, the challenge may be addressed by recruiting undergraduates trained in the physical sciences and engineering disciplines to the graduate study of physiology. There are increasing examples of how such students are intrigued by complex biological questions and the opportunities to apply their backgrounds there. This also offers the advantage that all students, including those trained initially in biology, benefit greatly from sharing diverse perspectives on a research question in the lab and lecture hall. Traditionally, a relative paucity of students with quantitative backgrounds has also been addressed by recruiting trainees from overseas. However, many countries are making substantial new investments in their research enterprise and intellectual capital, such as China. Indeed, the Council of Graduate Schools recently announced the smallest growth in the number of international students seeking graduate study in the United States in eight years, driven predominantly by a decline in the number of applications from Chinese students (www.cgsnet.org/ckfinder/userfiles/files/Intl_I_2013_report_final.pdf). Further, China and other countries with similar ambitions are actively courting ex-patriot faculty to return to well-funded laboratories (www2.itif.org/2012-leadership-in-decline.pdf). In the United States, we also face self-constructed hurdles to participating fully in the global talent market, such as an immigration system that makes it difficult to retain those students in whose education we have invested. Ultimately, this may impact the vigour not only of academic research in physiology, but also the medical and translational innovations that can drive economic development. As of this writing, however, there is some hope that the US Congress may enact comprehensive immigration reform that might be expected to address some of these issues.

Conclusions

In conclusion, therefore, this is a time of great promise, but also looming challenges for physiology in the United States. We are, however, very much still ‘open for business’ and expect to remain a destination of choice for those seeking advanced training in the discipline from all over the world. Indeed, even with budget cuts, the United States still makes the world’s largest investment in biomedical research. We also anticipate an increased level of collaboration with our international colleagues and sister societies to further the cause of physiology worldwide. A recent example is our founding, with The Physiological Society, of a new open access journal, Physiological Reports, that we anticipate will inject new energy into the publishing programs of both societies while showcasing increased numbers of important papers in our discipline.

References

Patterson A, Bonzo J, Li, F., Krausz K, Eichler G, Aslam S, Tigno X, Weinstein J, Hansen B, Idle J & Gonzalez F (2011). Metabolomics reveals attenuation of the SLC6A20 kidney transporter in nonhuman primate and mouse models of type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Biol Chem 286(22), 19511–19522.

Yatsunenko T, Rey F, Manary M, Trehan I, Dominguez-Bello M, Contreras M, Magris M, Hidalgo G, Baldassano R, Anokhin A, Heath A, Warner B, Reeder J, Kuczynski J, Caporaso J, Lozupone C, Lauber C, Clemente J, Knights D, Knight R & Gordon J (2012). Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature 486(7402), 222–227.

Acknowledgements

We thank Marty Frank, Executive Director of APS, for careful review of this article.