Physiology News Magazine

Q&A: Back to school

Prominent figures in physiology share memories of their school days

Features

Q&A: Back to school

Prominent figures in physiology share memories of their school days

Features

Dame Nancy Rothwell

President, Vice-Chancellor and Professor of Physiology, University of Manchester

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.89.35

Dame Nancy Rothwell

President, Vice-Chancellor and Professor of Physiology, University of Manchester

What did your school reports say about you?

I can’t remember my first school reports. The grammar school reports started off well, because in the beginning I was hard working and focused. But then I seriously got into sport and doing things other than work. So mostly the reports were, “If Nancy could apply herself more, she’d do better”. There was an awful lot of “More effort and she could achieve a great deal more”. They got a bit better when I got into studying specialist subjects. But, in general, “Could do better”. That included science up until about 15. But I didn’t like biology – I dropped biology from the age of 14/15. My favourite subjects were maths, physics, chemistry, art – all of which I did at A-level – and Latin. I know it was a strange combination!

What is your earliest memory of science at school?

My father was a biology lecturer at the technical college that became Central Lancashire University, so at home we had skulls and animals in cases and jars. As far back as I can remember, there were biology books that I read – even though I wasn’t that keen on biology at school. It was all around me.

At school, I loved physics and chemistry, but biology was more interesting at home. I don’t really have much recollection of biology at school. The early part of biology was an awful lot of classification and plants and things. It was a fairly classical education. I still can barely tell you the difference between one flower and another. I’ve always been more interested in animals.

What at school inspired you to pursue science or physiology?

In terms of formal education, I did come to physiology late. My first thought was to try to pursue a career in art – I went to art school to do my A-levels. But I wasn’t really good enough to make money out of it. My second choice would have been maths. Physiology wasn’t, in the end, a particularly well thought through decision!

My choice of subject and university were largely non-academic. I chose to do physiology and biochemistry, and changed to physiology. But that was only because of my father, who was a physiologist. My first practical at university I hadn’t a clue what I was doing, because I hadn’t done biology for four years. My father rightly advised me to stick with maths, physics and chemistry – you can pick up on the rest. My choice of university was largely social. I wanted to go to London. I went to Queen Elizabeth College, that later became part of King’s, and it was on Kensington High Street. And that seemed like a fun place to go.

Can you tell us about a particular lesson, experiment or incident in your science education that has stuck with you to this day?

We had a chemistry teacher who often blew things up. Mr Miller – Derek Miller. He was good fun. We would play with mercury and break all the rules. In general, we did things that you wouldn’t be allowed to do now. He was continually told off for doing things he shouldn’t. We had mercury on the desks, threw sodium into water and did all sorts of things. He was probably my most inspirational teacher.

We also had a physics teacher with a background in industry, so he could tell us all about how a nuclear reactor worked from first-hand experience. They were much more hands on than my biology teachers. I just happened to have chemistry and physics teachers who could talk about the real world. They also talked about the history of discovery, which I found fascinating.

Can you tell us about your first year at university? What impressed you the most?

At university, the first year I worked very hard. The second year I didn’t do much work – I missed most of the lectures. I just had a good time and I didn’t know what I was going to do. Then it was a research project in the final year with Mike Stock, who became Professor of Physiology, that completely changed things. I was looking at fat cell metabolism and how it changes in response to the physiological state of the animal. It was looking at rates of lipolysis and lipogenesis. It actually resulted in a presentation to a Physiological Society meeting, given by a final-year PhD student, Ian MacDonald (now Professor of Physiology in Nottingham). I went on to do my PhD with Mike and worked with him for a number of years. I’d gone to Mike Stock because he was an inspirational teacher and he taught human physiology, which was interesting to me. He worked on extremes: high-altitude physiology, hyperbaric physiology – so he worked a lot with the Navy. So I wanted to do a project on one of those, though I ended up doing one on energy balance regulation. I then worked with him until I left St George’s in 1987 to move to Manchester on a Royal Society fellowship.

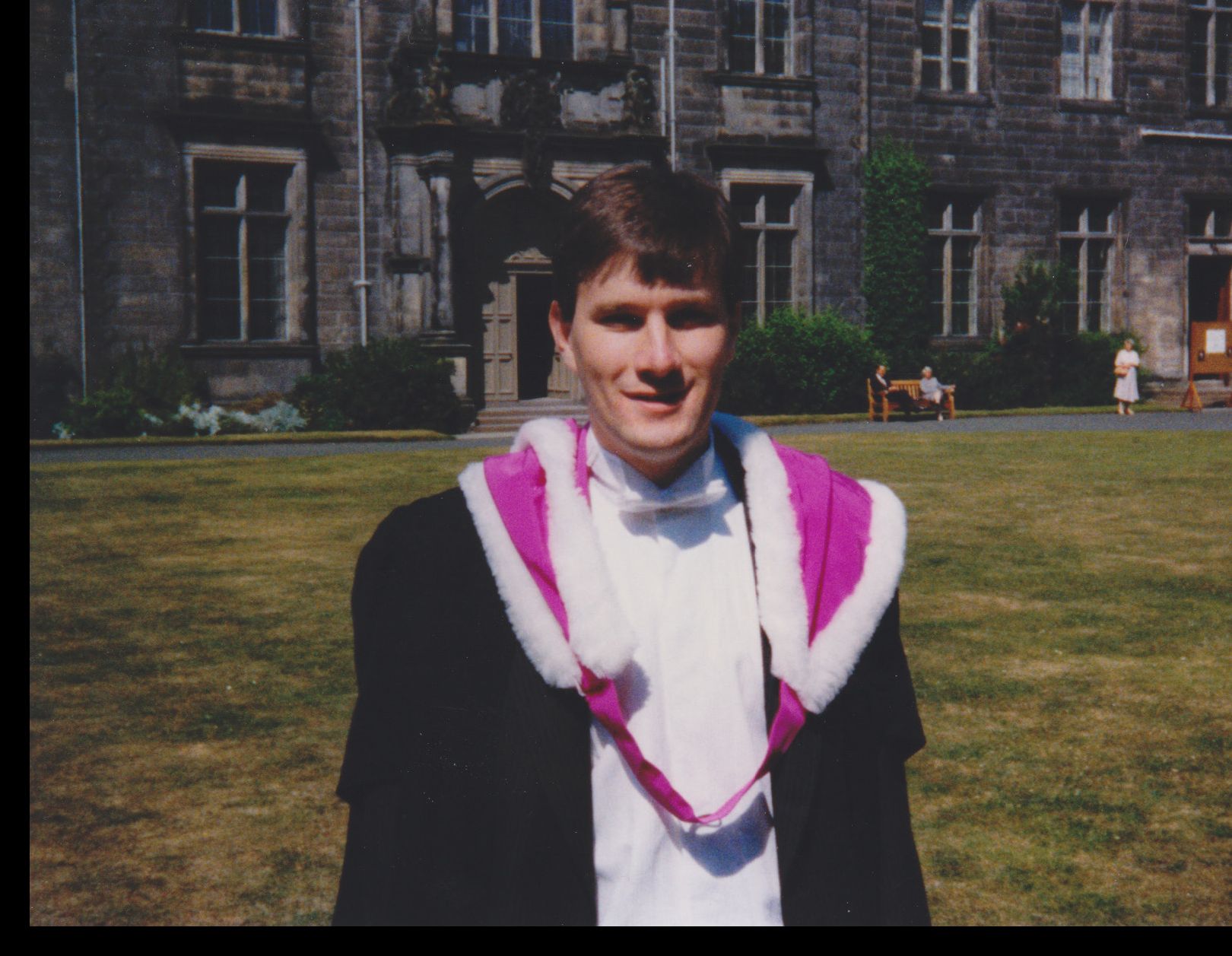

Mike Shipston

Professor of Physiology, Centre for Integrative Physiology, University of Edinburgh

What did your school reports say about you?

Certainly in my early days at senior school it would be along the lines of: “Quiet boy who is a good all-rounder, but hopeless at French!” My teacher despaired of my inability to speak French with anything but a broad Lancashire accent. However, inspired by a new teacher, I achieved a B grade at O-level – one of my proudest achievements!

What is your earliest memory of science at school?

Although I remember the typical ‘sand and water’ experiments at primary school, it was never something I associated with ‘science’. ‘Science’, as I perceived it, was gained from books, TV (Tomorrow’s World) and through a weekly children’s magazine (now defunct) Look & Learn. In fact, I remember in those days that ‘science’ was the exciting new thing you were going to do at senior school.

At first it was taught as one subject that mainly seemed to involve looking at soil. It was not until the second or third year of senior school that we had separate biology, chemistry and physics classes and I felt that I was finally doing real ‘science’. There was only one biology class and I had to fight hard to get a place in it.

What at school inspired you to pursue science or physiology?

From an early age I remember wanting to be a chemist. I’m not really sure where this desire came from as science was not something that ran in the family. I remember ‘helping’ my father when he rebuilt a VW Beetle engine and I was fascinated by how these hard, inanimate objects fitted together to make something so dynamic and apparently alive. Receiving a chemistry set one Christmas led to the inevitable construction of stink bombs, minor explosions, vinegar and Alka Seltzer volcanoes and wonderful crystal gardens. The latter led to my interest in biology. I left a saturated jar of sugar crystals outside in the shed for too long and came back to see, not a great crystal, but an amazing array of fungi and bacteria spilling out from the top of the jar.

Around this time I was inspired by three publications: One holiday I picked up a copy of The Protozoa by Vickermann & Cox; Richard Dawkins’ The Selfish Gene left its mark on me one summer in Cornwall; I then raided the library to find out more about cells and found a small book called A Prelude to Physiology – the combination of simple chemistry, physics and physiology had me hooked. This was reinforced in biology class at school with the classic experiments of taking a scraping of cells from the inside of your own cheek and observing them under the microscope, and making thin sections of leaves (using a razor blade to slice a leaf held between two bits of polystyrene) to observe the intricate cellular structure of leaves and their stomata.

Can you tell us about a particular lesson, experiment or incident in your science education that has stuck with you to this day?

In the first year or two at senior school we did an experiment with colour blindness charts. I vividly remember being the only student who could ‘see’ a particular pattern and being overjoyed at being the only one with my hand up. Of course, it turned out that I saw a different pattern to everyone else because I am red–green colour blind. Although teased mercilessly by my classmates afterwards, it left me with a sense of wonder at how diversity is generated – and also that being different was actually quite exciting. I remember getting a book from the local library with colour blindness charts, testing my family and tracking how it followed the X-chromosome.

Can you tell us about your first year at university? What impressed you the most?

I was taking biology, chemistry and physics courses – all of which allowed me to expand my horizons. It was the sense of freedom to explore these and other topics. While I was a fairly diligent student in attending my classes, and loved the practicals, I would often drop into the odd art history seminar that piqued my interest. Having a circle of friends whose interests spanned the arts, humanities and sciences certainly led to many interesting and lively discussions. With St Andrews being such a small place, you felt part of the fabric of the university.

Are there any teachers or tutors that had a particular impact on you?

At senior school my early chemistry and biology teachers, Mr Matthews and Mr Carah, were inspirational – they had very different teaching styles, but had a love of their subject and allowed you to explore and make the subject fun. Other teachers affected me in different ways – my final French teacher (I forget his name) never gave up on me and gave me the confidence to believe in myself. He was the polar opposite of my first French teacher, a dour French lady!

At university there were several lecturers who stood out, but perhaps most of all were Jim Aiton and Gordon Cramb. I managed to spend time in their labs during two summer vacations. Even though one project was assaying human urine, it was great fun and I learnt so much and developed a real love for trying to work things out for myself.

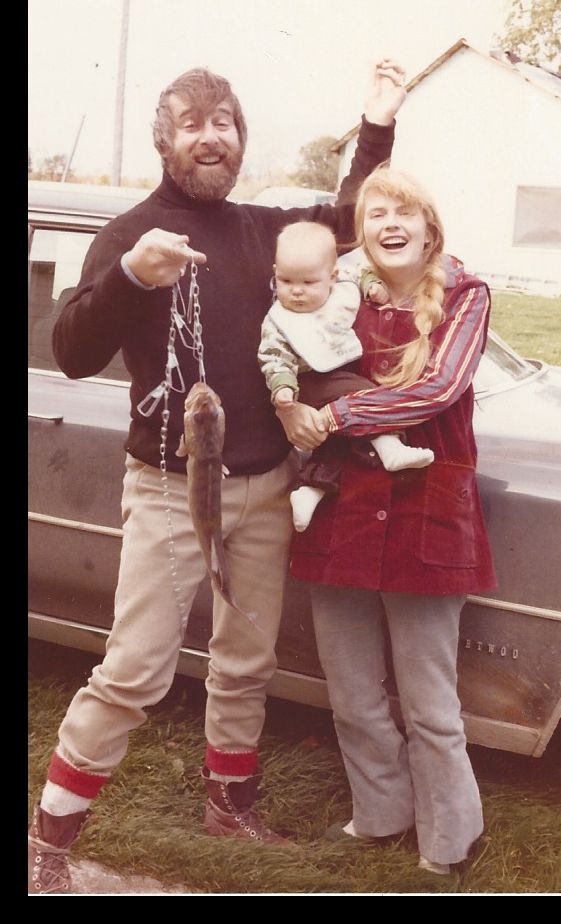

Holly Shiels

Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Manchester

What did your school reports say about you?

“Enthusiastic, but lacks focus”! But also, usually, “A joy to teach”! The teachers thought that I should be more diligent, but I had a lot of interests. I really liked history and I really liked English, and I liked biology and I liked maths. The Canadian system is different because you don’t have the same level of specialisation, but even by North American standards, I was very broad.

What at school inspired you to pursue science or physiology?

My best science memory from school was when I went to the Canada-wide science fair. That was in the first year of high school, at 13 years old. I presented a project on ‘The most efficient airplane wing’. I re-did the Wright Brothers’ experiments in my own model wind tunnel. It was really cool.

It went really well and it was fun. I won the school, and then the region, and then the province, but I didn’t win Canada-wide. The province one was kind of embarrassing. I was so overwhelmed by winning that I got a nosebleed! I totally remember who won at the nation-wide event. It was a project on – I even remember the title – ‘Spatial memory: scent or stimuli?’ I remember thinking, “What a complicated title!” It was about brain function in mice in a maze. I figured it was fair enough! I wasn’t hard done by at all.

It happened every year. That was the only year I ever got beyond the school competition. I did try again, but I didn’t seem to have the knack in later years.

Can you tell us about a particular lesson, experiment or incident in your science education that has stuck with you to this day?

In my final year of high school, Marty Rich was my biology teacher and he was fantastic. I did well in the class and it made me want to continue with biology at university. Those were the days when in high school you still did major dissections. We all dissected cats. They were formalin cats and they absolutely stank, and when we opened mine it was really fat! I had the fattest cat in the whole class! Mr Rich helped me get rid of all the fat so I could find all the major organs, which was nice, because I was pretty grossed out! I was 17. We worked in pairs and each pair got their own cat. You don’t even do that in university these days. We did a full dissection – took out every major organ!

Can you tell us about your first year at university? What impressed you the most?

University was also very broad. I took biology, history, maths, political science, philosophy. I finally decided to go for science before my very final year, when you have to decide on your major. I went to a marine station in New Brunswick on the east coast of Canada called Huntsman Marine Station. It was a three-week course and it was the first time that I felt I was doing my own experiments. The professors helped us to think about things, but we did them entirely independently – we researched them, made up a plan, did the experiments, collected the data and made a full report. It was looking at nitrogenous waste excretion in inter-tidal fish. Most fish excrete nitrogen across the gill as ammonia, but to do that you need lots of water. So for inter-tidal fish that get stuck hiding in crevasses when the tide goes out, there is no water. The idea was that they would switch from excreting nitrogen as ammonia to excreting it as urea. So I went out on the seashore and collected these little fish and stuck them in dark chambers on some mesh and removed the water. Then I let them sit there and sampled the water underneath the mesh. And it worked, which I thought was fantastic! Eureka: Urea!

The supervisor I worked with in New Brunswick said, “You’re very enthusiastic! Would you like to do an honours project with me for your final year?” That was Louise Milligan, now one of the associate deans at the university, and also now a good friend. Louise was a wonderful mentor – and she was just as excited about things when they worked as I was. She spent a lot of time with me at the start, but let me get on with it once I could be trusted. We were basically chasing fish in a tank with a stick, but it seemed so high-tech! (That was to exhaust them so we could measure lactate accumulation in the muscle.) That was my first real study of fish muscle physiology.