Physiology News Magazine

Re-purposing a clinical device for the classroom:

The tale of teaching cardiovascular physiology with ultrasound

Membership

Re-purposing a clinical device for the classroom:

The tale of teaching cardiovascular physiology with ultrasound

Membership

Dr Etain Tansey, Dr Sean Roe, Dr Chris Johnson

Centre for Biomedical Sciences Education, Queen’s University Belfast, Northern Ireland

https://doi.org/10.36866/122.46

The David Jordan Teaching Award is a grant to enable awardees to carry out a piece of educational research or to develop an educational resource that is relevant to physiology. This award recognises innovation in physiology teaching.

In 2015, we used it to purchase a portable ultrasound system. Our aim was to investigate the effectiveness of ultrasound technology as a tool for teaching cardiovascular physiology, a novel use of ultrasound at the time.

Previously we used more primitive and bulky machines (usually donated by clinical colleagues) that required extensive technical expertise to operate (referred to in the ultrasound literature as “knobology”) to achieve mediocre images. However, the award of £10,000 meant that we could purchase a basic but modern machine that was easy to operate but produced good-quality images. This use of ultrasound is quite separate from using it as a clinical tool that focuses on how to conduct

various examinations.

Rather, we use it to image the heart and blood vessels as they undergo physiological changes and have found it works incredibly well for underpinning the understanding of some core physiological concepts.

Informally, even when colleagues see how ultrasound imaging can be used to aid physiology teaching of, say, the Frank–Starling law of the heart, or the consequences of a supine posture with legs raised on venous return, they are struck by the immediacy of such demonstrations and how obvious it is to apply the technology in this way (1).

It is also immensely popular with students. In the first stages of our project, we used ultrasound imaging to bring to life the theoretic basis of cardiac physiology in a laboratory environment through live demonstration. Chris was trained (many years ago!) in cardiac ultrasound techniques in his former life as a clinical physiologist in cardiology and therefore performed the image analysis. Student satisfaction and enjoyment of these practicals was measured by Likert scores (where statements about the practicals were awarded a score from 1 to 5 depending on whether students strongly disagreed with the statement (scoring 1) or strongly agreed with the statement (scoring 5) with neither agreeing nor disagreeing scoring 3). Their learning was assessed by self-perceived understanding before and after the practical.

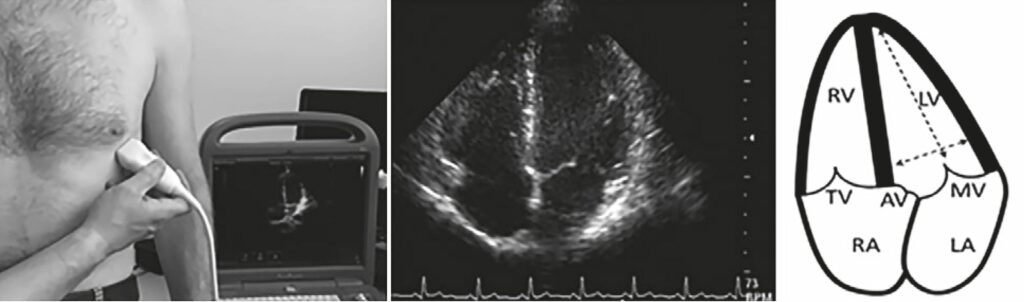

Students were asked to measure cardiac dimensions in systole and diastole and thereby derive, from first principles, important measures of cardiac function such as stroke volume (SV), ejection fraction (EF), and cardiac output (Fig. 1). We then were able to demonstrate how SV and EF increase after a subject performed a brief period of exercise, which led to discussions about factors that affect cardiac performance.

In self-reported results, 52% of students stated that they understood the Frank–Starling Law better after the class, 94% of students felt that performing calculations helped their understanding of the underlying physiology and 89% of students stated that they enjoyed the teaching session.

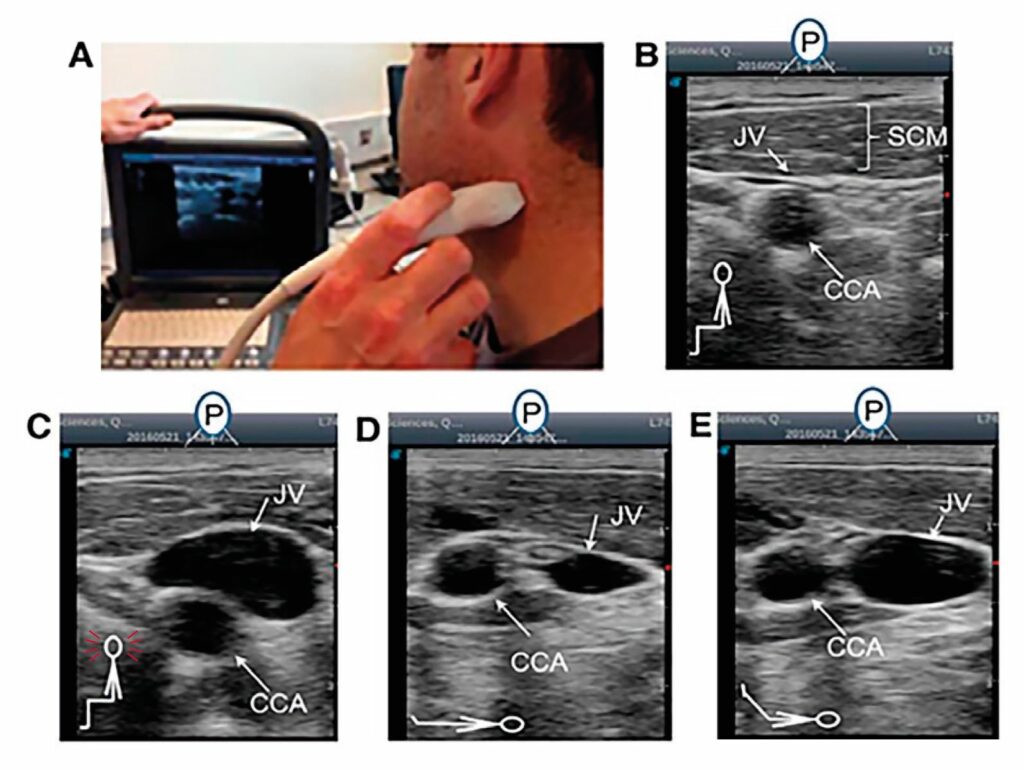

Ultrasound enables students to view and appreciate vascular physiology including venous phenomena such as the role of venous valves in ensuring blood returns to the heart, venous collapse of the jugular vein to measure central venous pressure (important in cardiac function), the various phases of the pulse in the internal jugular vein (reflecting right atrial pressure) and how it is affected by changes in intrathoracic pressure induced by speech and the Valsalva manoeuvre. 84% of students strongly agreed that ultrasound enabled them to see the clinical application of understanding venous pressure.

The successful execution of the first series of experiments resulted in three poster presentations at the main meeting of The Physiological Society in Dublin in 2016. On the back of this, we won a local rapid- fire presentation teaching award and we published two peer-reviewed papers in Advances in Physiology Education (2,3).

The final phase of the investigations is underway with a paper currently in preparation on the change in performance in simple “Single Best Answer of 5” examination questions before and after practical classes, comparing conventional classes with “enhanced” practicals using ultrasound machines to illustrate the concepts.

The preparation of this manuscript has illustrated the difficulty in assessing deep learning by means of simple before-versus- after examinations, with deep learning being predicated on a prolonged and enthusiastic engagement with the material, with the results being inconclusive. Perhaps, assessing enthusiasm and engagement is more appropriate in this arena, as what we aim to enhance is the more subtle and indefinable property of enthusiasm, passion and engagement with the topic.

These thoughts are reflected by other pedagogic researchers such as Professor Ian Turner from the University of Derby, UK, who is developing interesting ways to “gamify” classes using videos/animations, visualisers, theatrical props (termed 3D display) and lecturer interaction to make them more theatrical, challenging and fun (4).

The question “how do we measure learning after a two-hour class” may indeed need to be replaced by the more interesting question “how do we objectively measure fun”.

This need to enhance deep learning and engagement by making classes more theatrical and interesting has led us down some interesting pedagogic pathways since receiving the David Jordan Teaching Award.

Directly out of the contemplation of the results of the last series of experiments came a collaboration with the Department of Drama in Queen’s University Belfast and Dr Paul Murphy, on enhancing physiology tutorials by using acting students to play the part of patients. This nascent research has already been presented at the Aberdeen meeting of The Physiological Society (2019) and has been the subject of an invitation to the Mind Reading 2021 conference in Dublin on collaboration between artists and scientists.

So, although we continue to document the uses of ultrasound as a teaching tool and investigate its uses in the teaching of both anatomy and physiology, the David Jordan Teaching Award has led the investigators down other paths, which are proving fruitful and challenging.

The David Jordan Teaching Award was a godsend for us, as there is very little money available for education research, and what little there is has to go around all educational sectors, not necessarily physiology-related.

On a personal level, Chris knew Dave Jordan as a colleague and a mentor during his PhD, and without Dave’s initial encouragement to consider lecturing as a career, he may well not have pursued it. When we received the grant, we felt we were, collectively, under his nurturing influence.

References

- Levick JR (2010). An introduction to cardiovascular physiology. Hodder Arnold, London

- Johnson CD et al. (2016). Ultrasound imaging in teaching cardiac physiology. Advances in Physiology Education 40, 354–358. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00011.2016

- Johnson CD et al. (2020). Using two-dimensional ultrasound imaging to examine venous pressure. Advances in Physiology Education 44, 262–267. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00103.2019

- Turner IJ (2014). Lecture theatre pantomime: a creative delivery approach for teaching undergraduates. Innovative Practice in Higher Education 2(1).