Physiology News Magazine

Recognition for education and teachers in universities

Has anything changed in the last six years?

Features

Recognition for education and teachers in universities

Has anything changed in the last six years?

Features

Judy Harris, University of Bristol, UK

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.119.28

Introduction

The social distancing necessary during, and probably beyond, the Covid-19 pandemic is having major implications for all aspects of university life. Within education, lecturers are having to devise wide-ranging strategies and materials for distance teaching, learning and assessment to ensure that the quality and rigour of undergraduate education is maintained in these extraordinary times. So it is particularly timely to provide an update on The Physiological Society’s work in exploring the value that universities place on education, and how they recognise and reward the staff who specialise in developing and delivering it.

This is an area in which The Society has long taken an interest. The Education and Teaching Theme surveyed Society members in 2011 and concluded that “teaching and research achievements are rarely seen as being of equivalent status [in achieving promotion]” (Harris, 2011).Two years later, a survey of over 250 academics across bioscience departments and medical schools was conducted by the Academy of Medical Sciences, The Physiological Society, Heads of University Biosciences and the Society of Biology. Their report concluded that “the low status and undervaluation of teaching contributions, compared with research, disadvantages many academics who use teaching as a strand of evidence for progress in their academic career” (Improving the status and valuation of teaching in the careers of UK academics, 2014) .

In 2019 we followed up this work by launching a cross-STEM survey to all members of The Physiological Society, the Institute of Physics, the Royal Society of Biology and the Royal Society of Chemistry. The aim was to explore any changes in this area over the last 6 years, perhaps catalysed by the introduction of the Teaching Excellence Framework. This article presents findings from 193 respondents working as academics in either biosciences (144) or medical/health sciences (49). Focusing on the bioscience/biomedical disciplinary sub-group of STEM respondents has enabled some comparisons to be made with the data obtained in the 2013 survey, although it should be borne in mind that individual respondents in the two surveys are unlikely to have been identical.

Demographics of respondents

Survey respondents were self-selected but nevertheless represented a good geographical spread across the UK and a wide range of institutional mission groups. Around 50% of respondents worked in Russell Group universities with the rest spread fairly equally between institutions in the University Alliance, the Million+ Group and independent institutions. There was a good gender balance (43% female, 53% male, 4% preferring not to say), and a good cross-section of both age profile and career level across the sector. 40% of the respondents were in teaching-focused roles, 57% were contractually engaged in both teaching and discipline-based research with 3% describing themselves as research-only. This distribution of contractual roles across respondents is important in showing that the survey responses reflect the views of both teaching-focused staff and of academics for whom teaching is just one strand of their role.

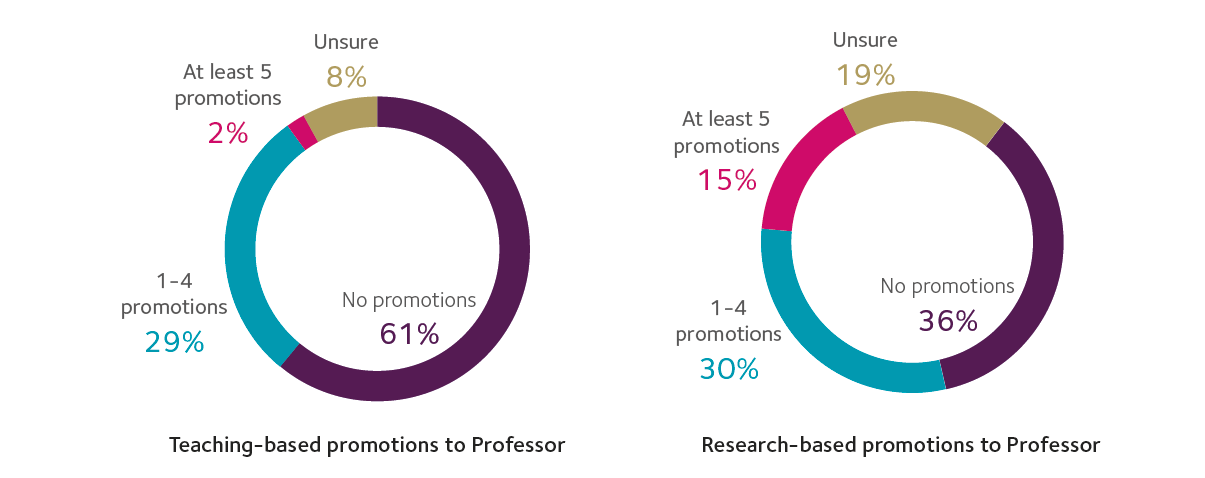

Career progression and recognition/reward of staff

Although many universities either have, or are in the process of introducing, a career path for teaching-focused staff, only 60% of respondents reported being aware of the existence of a career path in their institution that enabled promotion to professor on the basis of educational achievements. In the 2013 survey that figure was 75% which suggests that awareness amongst staff of the opportunity for such promotion has certainly not increased over the last 6 years. Figure 1 compares the number of respondents reporting promotions to Professor/Chair in their home department on the basis of teaching vs discipline-based research achievements. It is clear that many more of the reported promotions to Professor are based on research achievements. This is likely in part to reflect the relative numbers of staff employed on teaching-focused contracts vs ‘balanced portfolio’ contracts of research & teaching. However, for over 60% (118/193) of respondents to be unaware of a teaching-based promotion to Chair in their own department over the last 3 years suggests that such opportunities are thin on the ground. In the 2013 survey, 65% of respondents were similarly unaware of anyone who had been promoted to Chair via a teaching route. This suggests that very little, if any, progress has been made in this area in the last 6 years. As well as being demoralising for experienced/senior teaching-focused staff, this provides little incentive for younger staff to opt for an education-focused career path and few role models for aspiring educational leaders.

There were many free text comments on this subject, of which the following are typical:

- As is typical in the sector it is more difficult to become a teaching focused professor than a research professor. Criteria for award of teaching professorships are not transparent, very variable across the sector and set at a very high bar so as to be almost unachievable. Universities only pay lip service to this pathway.

- While it is technically possible to get promoted to Professor/equivalent on a teaching-focused career pathway at my university, realistically it’s likely to be unobtainable based on metrics against which candidates would be assessed.

- Metrics are clearer for research-focused staff and the university seems much clearer on promotion panels what they are looking for. The teaching requirement for these applicants seems much more flexible than the research criteria are for teachers with similar applications.

A recurring theme in the comments was that, whilst it is theoretically possible to become a teaching-focused professor, in practice such promotions are rare. This echoes the results of the 2013 survey in which 55% of respondents stated that, although a system for promotion to professor on the basis of achievements in Teaching and Learning existed in their institution, this was largely a theoretical route rather than one that operated in practice. Another recurring theme in the current survey was that staff, external assessors and promotion panels are often unclear what needs to be achieved for teaching-based promotion and how to evaluate those achievements. There was a widespread view that this leads to confusion and disparity of practice between institutions, in contrast to research-focused promotion practices for which there is much better consensus and transparency on the metrics and criteria for promotion across the sector. Such disparity across the sector is clearly undesirable. Worryingly, over two-thirds of the teaching-focused respondents in the current survey considered that the promotion criteria on a teaching-focused pathway are harder to achieve than [for equivalent positions] on other career pathways, or are simply not achievable.

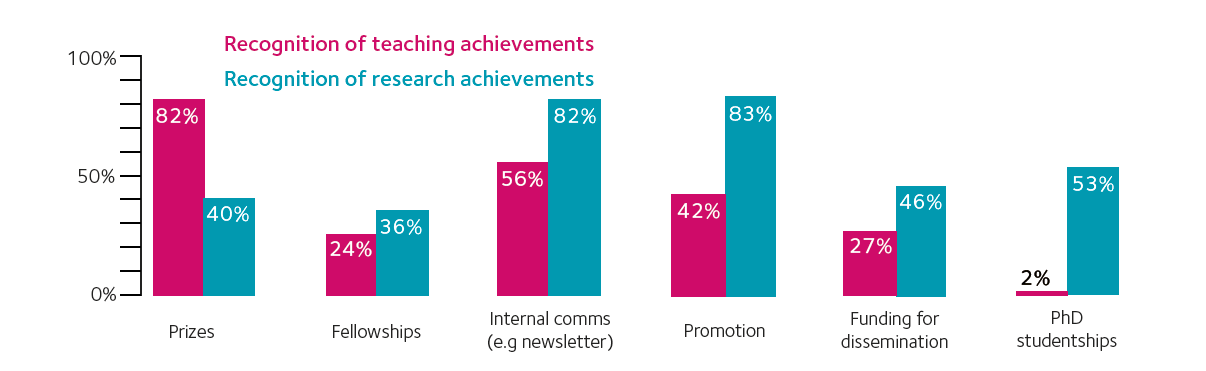

Further differences between the ways that universities recognise teaching and research achievements are revealed in Figure 2. This shows that the award of prizes is the only indicator of excellence that is conferred to a greater extent on teaching achievements compared with research achievements. It is encouraging that the prevalence of teaching prizes seems to have increased over the last 6 years since only 62% of respondents reported their existence in the 2013 survey, compared with the current 82%. However, other rewards for excellence, for example the award of Fellowships, PhD studentships and funding for the dissemination of outcomes, are ‘earned’ to a much greater extent by discipline-based research achievements (see Fig 2). This disparity is important because the latter awards are often more substantive than a one-off prize (welcome though that may be) and they often enable recipients to build on, and extend, their past success.

Support for Continuing Professional Development

The 2019 survey revealed some troubling findings in the area of Continuing Professional Development (CPD), regardless of respondents’ contractual roles. For example, less than half of all respondents (74/193) reported having been assigned an effective mentor and a quarter of all respondents (52/193) reported that no tangible support for CPD (e.g. funding to attend external research or educational conferences/workshops) was provided by their institution. There was a very similar pattern of responses from teaching-focused staff compared with staff having a balanced research-teaching portfolio. However, the absence of institutional funding for CPD is especially significant for teaching-focused staff who are almost entirely dependent on their institution to provide such funding, whereas external research grants may provide some funds to support conference/workshop attendance by researchers. Furthermore, of the respondents whose contract specifically included the requirement to carry out Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL), 40% (23/58) of them reported that they have no time to do this because of other heavy contractual obligations. When faced with deadlines to prepare teaching, set/mark assessments and devise courses, it is understandable that SoTL will take a back seat despite the fact that scholarship, with publication of its outcomes, is likely to be crucial for such staff to achieve promotion success.

The outcomes of all these factors are clearly illustrated in Figure 3 which shows that teaching-focused staff are less likely to attend teaching conferences, compared with attendance at research conferences by research-focused and ‘balanced research-teaching portfolio’ staff. This will undoubtedly put teaching-focused staff at a disadvantage, compared with staff who engage in discipline-based research, in terms of keeping up with current developments, networking and sharing good practice, as well as building an external profile. These are important activities in achieving individual progression/promotion on any career pathway. In education, as well as in research, they are also vital in enabling practice and knowledge to advance, and in creating the collaborations and agility so essential to the sector as a whole being able to respond to external stimuli such as the current pandemic.

Attitude of senior management

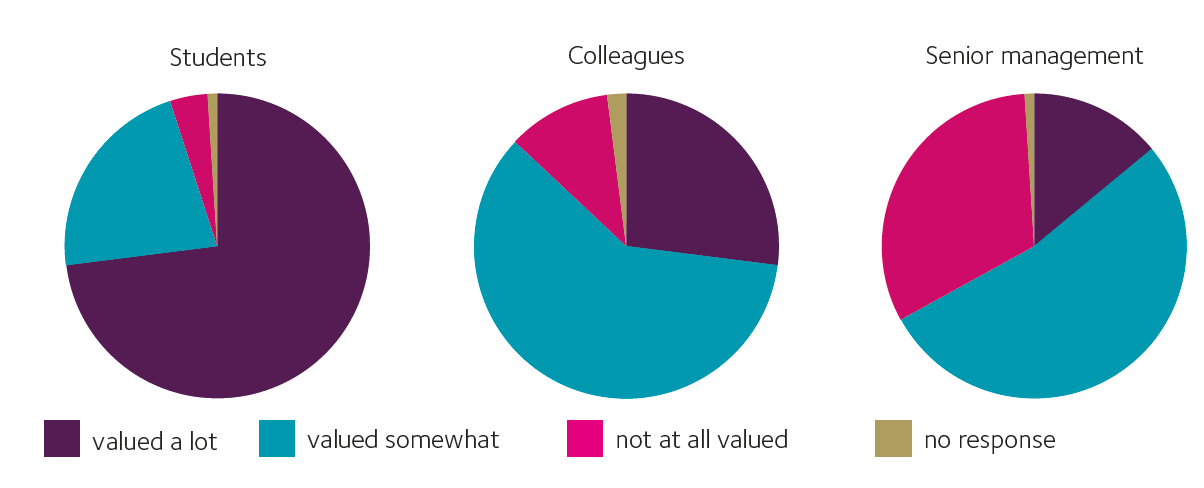

Figure 4 reveals a troubling, and potentially high impact, finding of this survey – nearly a third of respondents consider that teaching-focused staff are not valued at all by senior management within their institution. This perception was the same regardless of the contractual role of the respondents. It is heartening to see that the perceived value placed on teaching-focused staff by students, and to a lesser extent by colleagues, is high. However, any perceived undervaluing of teaching-focused staff by senior management is a serious concern given the impact it is likely to have on institutional practices and staff morale.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the 2019 survey results demonstrate that there has been very little progress over the last 6 years in the way that teaching-focused staff are valued, recognised and rewarded in universities. Whilst there are undoubtedly variations between institutions in their practices and attitudes, the views of the staff who responded to this survey provide little evidence for progress across the bioscience and medical/health science sector in general. It seems that the introduction of the Teaching Excellence Framework has done little or nothing to improve the status of teaching-focused staff despite the government’s aspiration in the original White Paper3 that “At the institutional level, our HE and research reforms are intended to balance the incentives on institutions and establish parity for academics who build a career in teaching as well as in research or a combination of both”. Who knows when/whether such parity might be achieved but The Society is committed to considering ways in which it could contribute. This could include facilitating the mentoring of younger, teaching-focused staff by more experienced staff and offering more support to members to share good practice at teaching-focused meetings and workshops (currently probably through virtual events). The data also highlight the need for the sector to explore how institutions might be encouraged to improve parity between research and teaching through establishing a clear career structure for university teachers, which is consistent and transparent across the sector.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to Chrissy Stokes, Head of Professional Development and Engagement at The Physiological Society and to Derek Raine, Co-chair for the Society of Natural Sciences and Professor (Emeritus) at the University of Leicester, for all their input in designing the survey and its subsequent dissemination, analysis and interpretation. I would also like to thank staff at the Royal Society of Biology, the Royal Society of Chemistry and the Institute of Physics for their input to survey design and for publicising the survey to their members. Thanks also go to all the survey respondents for generously giving up their time to complete the survey.

Judy Harris is an Emeritus Professor at the University of Bristol. Her teaching development activities included contributing to the development of high fidelity simulation-based, undergraduate physiology teaching, creation of on-line resources for laboratory-based teaching through the e-Biolabs system and evaluation of histology teaching delivered using a ‘virtual’ microscope. Her other interests included developing and evaluating the use of undergraduate peer assessment.

References

- Harris, Judy R (2011). The status and valuation of medical sciences teaching in academic careers: some progress but room for improvement? Physiology News 85, 48-49.

- Improving the status and valuation of teaching in the careers of UK academics (2014). Academy of Medical Sciences, The Physiological Society, Heads of University Biosciences and the Society of Biology. https://acmedsci.ac.uk/file-download/35825-53b11f4d0fa27.pdf

- Success as a Knowledge Economy: Teaching Excellence, Social Mobility and Student Choice (2016). UK Department for Business Innovation and Skills https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/523546/bis-16-265-success-as-a-knowledge-economy-web.pdf