Physiology News Magazine

Remembering the 150th anniversary of the birth of Adolf Beck (1863-1942)

Polish-born physiologist, co-developer of electroencephalography who suffered persecution in two world wars and committed suicide facing arrest by the Nazis

News and Views

Remembering the 150th anniversary of the birth of Adolf Beck (1863-1942)

Polish-born physiologist, co-developer of electroencephalography who suffered persecution in two world wars and committed suicide facing arrest by the Nazis

News and Views

Oksana Zayachkivska

Department of Physiology, Lviv National Medical University, Lviv, Ukraine

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.94.12

Adolf Beck was the founder of the Physiology Department in the Medical Faculty, the National Medical University in Lviv (formerly known as Lemberg, 1772–1919, or Lwów, 1340–1772 and 1920–1939), western Ukraine. He was not merely a scholar, with first-rate credentials for having developed methods for the study of the cerebral cortex and neurophysiology, but also a man of great personal courage.

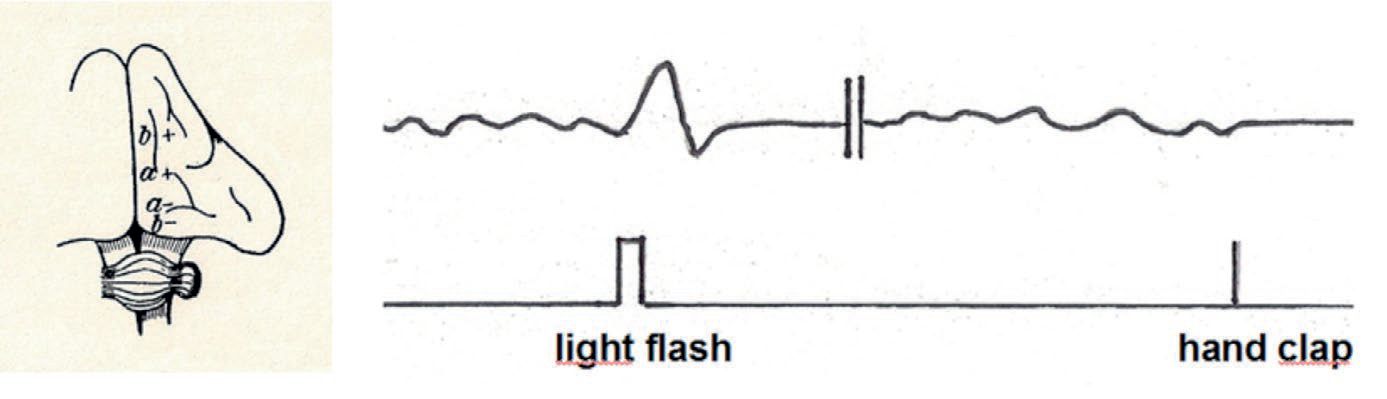

Beck was a pioneer in the development of electrophysiology and a co-developer of electroencephalography. He performed his influential work at his alma mater, the Jagiellonian University in Kracow, under the leadership of Napoleon Cybulski (1854-1919). In 1890, his article about the spontaneous and evoked electrical activity in the brain was published in the Centralblatt für Physiologie, then a leading European physiology journal. Beck accurately localised sensory modalities in the cerebral cortex by employing electrical and sensory stimulation whilst recording electrical activity. In doing this, Beck also discovered the spontaneous oscillations of brain potentials, just as Caton (1875) had done, and showed that these fluctuations were not related to heart and breathing rhythms, but had to be regarded as genuine electrical brain activity. Later, in the 1890s, Beck studied parts of the cerebral cortex that reacted upon stimulation with electro-negativity: the first recorded ‘evoked potentials’. Moreover, Beck discovered a new element: a decrease in the amplitude of the potentials upon sensory stimulation. Thus, he was the first to describe the phenomenon now known as desynchronization of the EEG. Beck published that work as his doctoral thesis (in Polish). Many years later, MAB Brazier (1904 –1995), the neuroscientist, international organizer and prominent expert in the history of neuroscience, translated the dissertation into English, placing Beck’s eminence in the company of such scientists as Gustav Fritsch, Eduard Hitzig, David Ferrier, Emil du Bois-Reymond or Ivan Sechenov (Brazier, 1973).

In 1895, Adolf Beck became head of the Department of Physiology and an appointed Professor at the newly renovated Medical Faculty of the University Franz I in Lemberg, in Galicia (at that time under the Austro-Hungarian monarchy). With great energy and enthusiasm, Beck organised the Department in very similar style to that of his alma mater and other European universities equipped with modern scientific apparatus and laboratories for chemistry and morphology. He organized an operating and vivisection room, and care rooms for experimental animals that made it possible to carry out extensive research. In the same year, together with Cybulski, Beck produced a report for the Third International Physiological Congress in Bern on their extensive electrophysiological studies of brain potentials. He took part in the organisation of the Eighth International Congress of Physiology in Vienna (1910) where, with Gustaw Bikeles, he presented data on The galvanometric study of the spreading reflex arc in the spinal cord. His originality and creativity in research attracted attention from the whole international community.

It is important to note that Beck’s research was not limited to neurophysiology. He also worked in fields of general physiology, such as visceral and sensory function and laboratory medicine. He also arranged a local physiological society and the Institute of Physiology of the university. He did not receive the Nobel Prize despite being nominated several times (as recently released records have revealed), but Beck’s academic oevre remains remarkable. It comprises 180 texts, many published in the most influential European journals. Also amongst his works are textbooks on the physiology of the central nervous system, and a two-volume Human Physiology (two editions) popular among medical students for many years. Beck’s teaching and pedagogical work merits special attention, as attested by the memoirs of his students.

He was reappointed Rector at Lemberg/Lviv in the difficult years of World War I. He manifested rare diplomatic skills under the extreme wartime conditions, using his diplomacy to make a convincing case for academic needs to the occupying authorities. He joined the efforts of those colleagues who remained in the city to protect the university’s property. However, in 1915 he was arrested by the Russian commandant and exiled. After a few months, Beck was released from prison thanks to the efforts of Nobel laureate Ivan Pavlov, and of the Red Cross. In 1935, he authored a memoir on the adversities endured in World War I, which became a sui generis chronicle of events at the university. He had a memory that retained the smallest details of the war in Lviv and these enliven the book. Beck’s persistence and tireless work ethic – he did not interrupt his research even in the difficult war and postwar days – were another element of his personality. Adolf Beck became a visionary in the development of societal relations. An ardent critic of Zionists, he founded and headed the ‘Unity’ organization, whose mission was to ensure equality among people of various ethnicities and religions, sentiments which resonates with the present day slogans of the European Union (Zayachkivska, 2013).

In the absence of a detailed personal memoire, truly understanding Adolf Beck, the man, remains a challenge. Did he sense danger in 1915 when he was imprisoned and deported to an evacuation camp in Russia? What emotions stirred in his breast in 1939, at the outbreak of World War II and the start of the ‘new’ Soviet era, or in 1941, when he was required to pin a Star of David to his garments and suffer Nazi persecution, or when the Janowska concentration camp was founded in Lwów? What were his final thoughts when, on the point of arrest by the Nazis, he took poison from his own son’s hands in order to commit suicide? We do not know the answers to these questions – but it is said that ‘each question contains part of an answer’. We can be confident that, under all the adversities he faced, Beck proved courageous, chose to do good and to honour cooperation. The sesquicentennial celebrations that took place at Beck’s alma mater as part of the Neuronus 2013 International Brain Research Organization (IBRO) and International Research Universities Network (IRUN) (Coenen et al. 2013), as well as a presentation of his life-story at IUPS, Birmingham, 2013, confirm that Adolf Beck offers a fine example of noblemindedness for future generations, and a person worthy of remembrance in the 21st century.

References

Brazier MAB (1973). Beck A: The determination of localizations in the brain and spinal cord with the aid of electrical phenomena. Acta Neurobiol. Exp. Suppl 3, 1–55.

Caton R (1875). The electric currents of the brain. BMJ 2, 278.

Coenen A, Zayachkivska O, Konturek S & Pawlik W (2013). Adolf Beck, co-founder of the EEG: an essay in honour of his 150th birthday. Digitalis/Biblioscope, Utrecht.

Zayachkivska O (2013). The world of Adolf Beck by eyes of Henryk Beck: total unofficial. BaK, Lviv. – 94pp.