Physiology News Magazine

Seventy years on

Charles Lovatt Evans retired at University College London

Features

Seventy years on

Charles Lovatt Evans retired at University College London

Features

Otto Hutter, Emeritus Regius Professor, University of Glasgow, UK

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.120.22

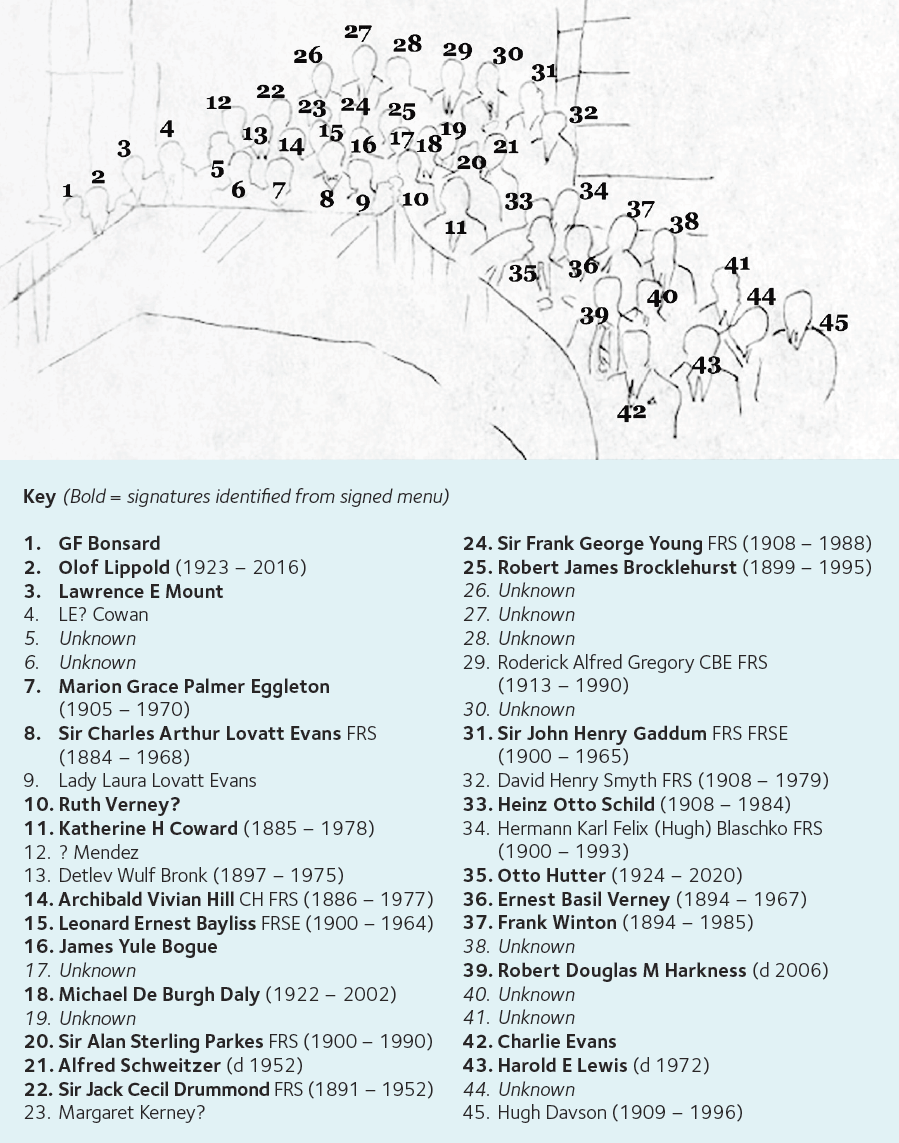

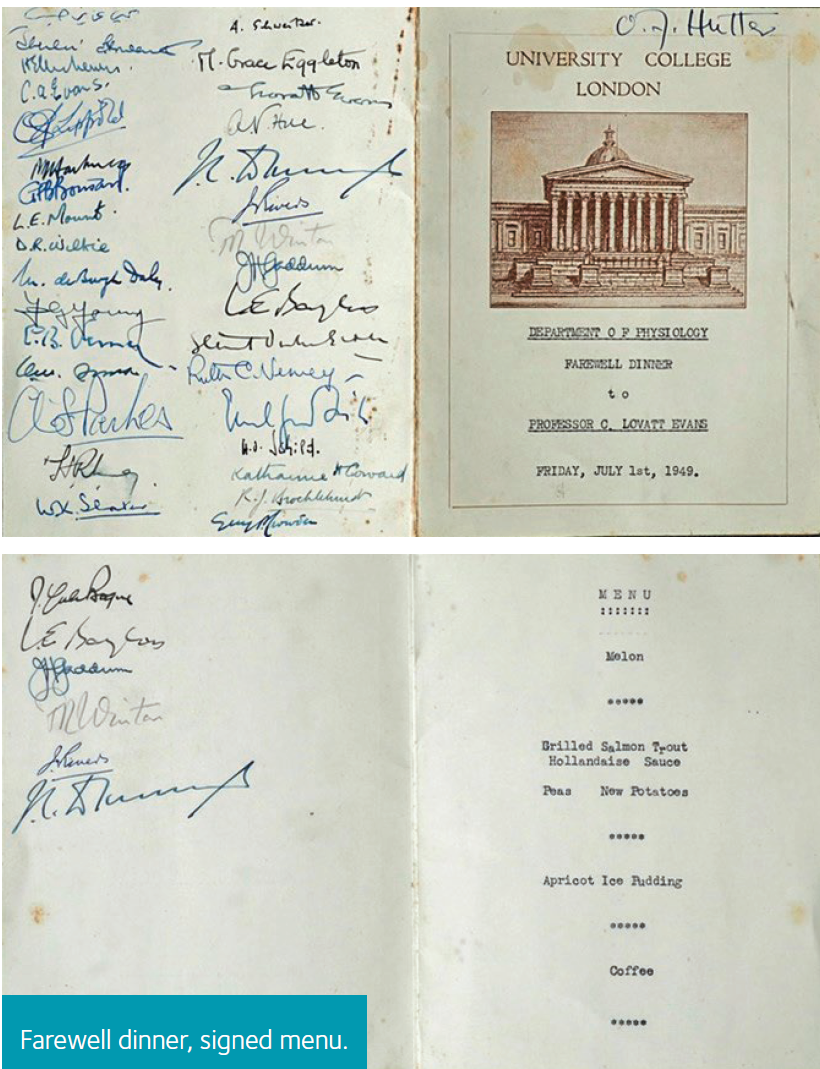

It was at University College London that Otto Hutter started his own long and distinguished academic career, studying in the Physiology Department, then headed by Charles Lovatt Evans. In 1949, Otto was able to attend the retirement festivities for Lovatt Evans described in this charming article. The signatures on Otto’s copy of the dinner menu, illustrated here, feature many Physiological Society greats.

The retirement in June 1949 of Sir Charles Lovatt Evans (1884 – 1968) from the Jodrell Chair of Physiology at University College London was the end of an era. At the dinner in Sir Charles’ honour, the menu cards were circulated to be signed by the guests, who then gathered for a group photograph at the physiology building. As Sharpey Scholar, I attended these festivities; and I have kept the signed menu card and the group photograph ever since, for I count Lovatt Evans as one of my benefactors.

On leaving school in 1942, I was a laboratory assistant at the Wellcome Physiological Research Laboratories in Beckenham, Kent. At first, I was engaged in the biological assay of insulin, then essential work in wartime as it was in peace. Encouraged by the senior staff, university lecturers who had been recruited for war work, I began to study physiology part-time. The 1941 edition of Starling’s Principles of Physiology, kept up to date by Lovatt Evans, became my principal text.

By the end of the war, I had completed the first 2 years of a BSc course at the then Chelsea Polytechnic. Our lecturer there was a youthful R A Gregory, who came up twice a week from Leatherhead, to where the University College London (UCL) Medical School had been evacuated. He delivered memorable lectures, especially those on gastric secretion, having just returned from B P Babkin’s laboratory in Montreal.

To fulfil my ambition to become a physiologist, I then needed to take a BSc Honours course; but such courses had been suspended during the war. So, after Victory over Japan (VJ) Day in 1945, I wrote to Sir Charles to ask when the honours course at UCL would be reinstated and to plead for admission. Graciously Sir Charles granted me an interview.

I arrived early one Monday morning in October 1945 and waited in the corridor joining the physiology and pharmacology staircases for Sir Charles to arrive from Porton Down [the Government research establishment]. The Admiralty then still occupied the rest of the Physiology Department. Only the rooms along that corridor had been released. After a while, a gentleman attired with a beige mackintosh topped with a Homburg hat came up the pharmacology staircase. He ushered me into his temporary office, put me at ease and kindly heard me out. Throughout he treated me, a mere youngster laboratory technician, with, to me, astonishing courtesy, as if I were a colleague. Much later, I learned that Sir Charles himself had an unconventional education and that he also sat for a London university degree in physiology as an external student.

In those days, the second MB (Bachelor of Medicine) course lasted five terms, and the intercalated BSc course four terms. So the first post-war BSc course did not start until April 1946. It was a small class consisting of two medical students of distinction, namely David Fryer, who sadly was later killed in an accident while serving in the RAF, June Hill, who became Mrs Douglas Wilkie, and me. Our teachers were Leonard Bayliss, Bernard Katz, F G Young for biochemistry and G P Wells for comparative physiology. But mostly we were guided to read and learn by ourselves. Under (Chief Technician) Charlie Evans’ watchful eye, we worked our way through Sherrington’s Practical Physiology (Mammalian Physiology: A Course Of Practical Exercises, 1919). An amplifier built by Bayliss in a National Milk tin and an oscilloscope purchased from an army surplus store allowed us to record action potentials.

A university studentship fell to me on the basis of the examination results. And as the first post-war science student with any extra laboratory experience, Sir Charles kept me back as demonstrator. After a year, he appointed me Sharpey Scholar, a post he himself held under E H Starling. As to how to start research, Sir Charles advised me first to repeat some interesting, published work: I was sure to find some discrepancy, requiring further investigation.

The Wellcome Laboratories in Beckenham, besides their research function, were also a production site: stables in the extensive grounds housed old army horses used for the production of tetanus anti-toxin. This had aroused my curiosity about the action of tetanus toxin. In particular, a paper by A M Harvey (1939) caught my attention. In it he claimed that tetanus toxin had a peripheral excitatory action that could be revealed by suitably timed injection of the toxin into a muscle before its motor nerve was severed.

If this were so, I thought, it should be possible to record spontaneous end-plate potentials from an excised muscle showing tetanus of peripheral origin. So bearing in mind Sir Charles’ advice, I started to repeat A M Harvey’s procedure. But try as I might, I could not repeat his observations. In my hands, a toxin-injected muscle never displayed tetanus once the motor nerve was cut (Hutter, 1950).

In the course of these experiments, a cat nipped the forefinger of my left hand. Weeks later a tiny irritating blister appeared, then my trochlear gland became enlarged and then that adenopathy engulfed also my axillary gland. I was eventually cured by massive doses of potassium iodide, prescribed by Professor Max Rosenheim, later President of the Royal College of Physicians. I was still under treatment at UCH when I slipped out to join the tribute to Sir Charles.

References

Harvey AM (1939). The peripheral action of tetanus toxin. The Journal of Physiology 96, 348-365. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.1939.sp003780

Hutter OF (1951). The decurarizing effect of a tetanus. The Journal of Physiology 112, 45 P. Published: 1951.

Putting Charles Lovatt Evans into context

David Miller, University of Glasgow, UK

Many readers of Otto’s delightful piece will, regrettably, hardly know the name of Lovatt Evans and little of his work. His current absence from Wikipedia hardly helps modern readers (a prompt perhaps to any willing Wikipedia writer?).

Sir Charles Arthur Lovatt Evans was born in 1884 in Birmingham. His unusual education and early career was gained in part as a technician and then as a lecturer at two colleges in Birmingham. Offered a scholarship by Ernest Starling, he worked at UCL from 1910. Medical training followed and then war work, together with Starling, on the challenges posed by gas warfare. He investigated the effects of arsine, phosgene, hydrocyanic acid, and mustard gas, as well as respirator efficacy. His rise in physiology was meteoric. In 1918, he was made professor at the University of Leeds, but 1 year later moved to London at the National Institute for Medical Research, Hampstead; from there he went to the Chair of Physiology at St Bartholomew’s Hospital (1922) and last to the Jodrell Chair of Physiology in UCL (1926).

His predecessors, Starling and AV Hill, were still at UCL and he collaborated with both. With Starling, he investigated the metabolism of the heart and lungs and the role of lactic acid in muscle metabolism. He published on cardiac, voluntary, and smooth muscle in relation to lactic acid and heat production. This work developed the “heart oxygenator” preparation, insights that laid the foundations for open-chest surgery. After retirement in 1949 he researched anticholinesterases, analysing how they affected respiration by bronchoconstriction, neuromuscular block, and central respiratory failure. He showed that sweating in the horse is controlled by circulating adrenaline rather than by nerves. His last published paper was on the toxicity of hydrogen sulphide, work done at the age of 83.

Lovatt Evans was among the first physiologists to recognise the importance of the then new subject of biochemistry, being a founder member of the Biochemical Society. Another major contribution was in editing and writing highly respected and influential textbooks (e.g. 14 editions 1930–58 of Starling’s Principles of Human Physiology, and authoring 4 editions of Recent Advances in Physiology). He was universally regarded as an inspirational leader with the prized ability to help people find their own way largely independently. He made major managerial contributions to the work of the Medical Research Council and in re-establishing UCL after World War 2. Knighted in 1951, Lovatt Evans died in 1968.