Physiology News Magazine

Sir Gordon Morgan Holmes

On the confluence of physiology, medicine, history, industrial design and art in war

Features

Sir Gordon Morgan Holmes

On the confluence of physiology, medicine, history, industrial design and art in war

Features

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.124.32

Dr Sean Roe, Queen’s University Belfast, UK

To the Dublin native working in Queen’s University Belfast, the small townland of Castlebellingham on the border is a convenient stop to get fuel and perhaps a sandwich when driving to visit family. To the student of Medical Physiology and the history enthusiast, it is the childhood home of a remarkable man. Gordon Morgan Holmes, born in Dublin in 1876, travelled far beyond his birthplace and authored a remarkable body of work borne of his experiences in Ireland, England, Germany, and, most notably, the Western Front of the First World War (Fig.1). It is to him that we owe much of our modern understanding of the functional anatomy of the visual cortex and the cerebellum. Many of the techniques still used to examine cerebellar and visual function were originated by him, under fire in casualty clearing stations, where, after long days on the line, he retired to make copious notes late into the night (Fishman, 1997). Here, in France, between 1915 when he arrived, and 1918 at the cessation of hostilities, existed a confluence of factors and personalities that lent themselves uniquely to the advancement of the science of neurology.

Cometh the man

Born in February 1876, Holmes, after local schooling, studied Medicine in Trinity College Dublin, after which, seized by a desire to travel, he enlisted as a ship surgeon travelling to New

Zealand. On his return to Ireland, he served as a resident medical officer in the Richmond Asylum (now St Brendan’s Psychiatric Hospital, Dublin). The earnings from these posts, as well as money awarded for the Stewart Scholarship in Nervous and Mental Diseases for Excellence in Anatomy funded further travel to study neuroanatomy in continental Europe. His European trips culminated in two years at the Senckenberg Institute in Frankfurt, Germany where he studied, principally with Ludwig Edinger, and learned staining techniques and histopathology with Carl Wiegert (Fine et al., 2011).

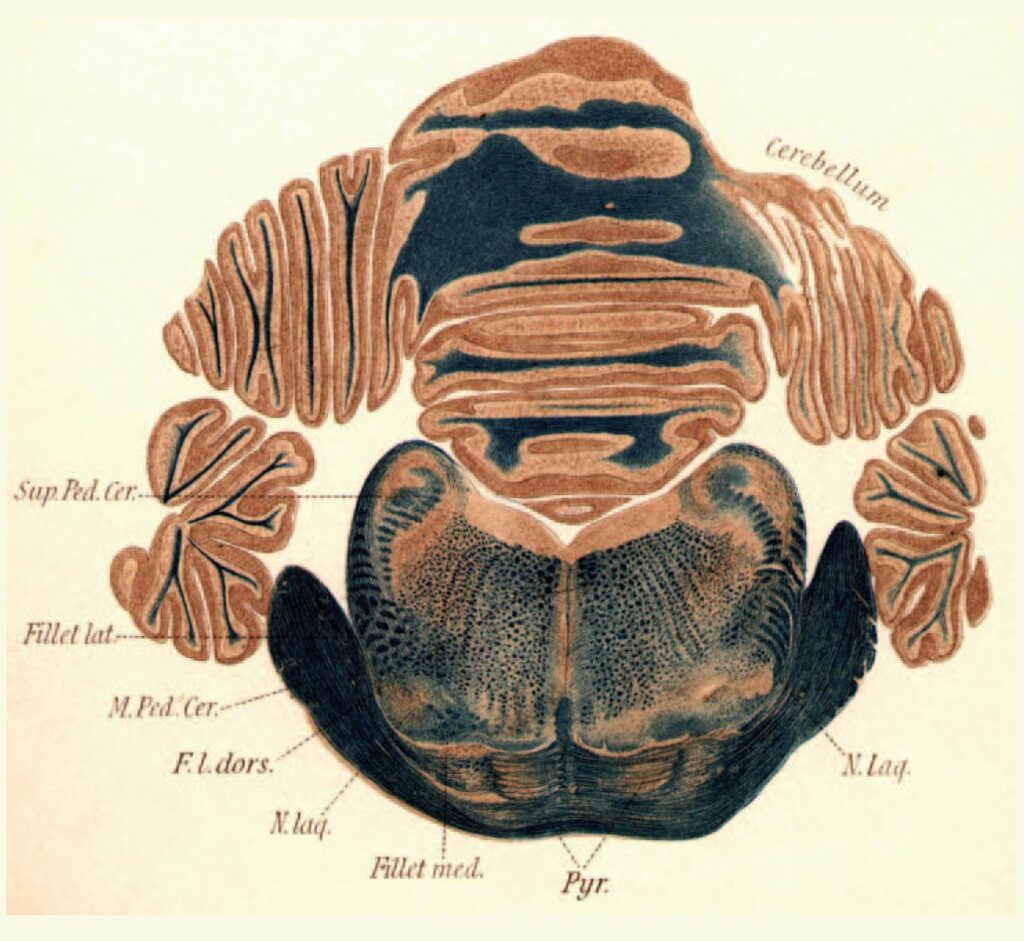

His education with the “Herr Professor” Edinger was challenging; sections of the spinal cord painstakingly drawn (over 2 days) were unceremoniously torn up when they did not reach the exalted standards required (McDonald, 2007). Soon after this, however, Edinger warmed to Holmes, so much so that he gave him the brain of Goltz’s famous preparation “dog without a forebrain” for detailed histologic study. The beautiful, almost artistic drawings resulting from this can be seen in Holmes early work for The Journal of Physiology (Fig.2). This exacting early training in neuroanatomy, physiology and histology would serve Holmes well in his later life, where these skills combined to inform some of his most important discoveries.

On returning to Ireland from Germany, he applied for a post as registrar at the National Hospital, Queen Square, London, and in 1903 received his MD and gained membership of the Royal College of Physicians in London in 1908 (Breathnach, 1975). In Queen Square, under the mentorship of John Hughlings Jackson the skills of “unresting contemplation of the facts of observation, scrupulously and untiringly acquired” were inculcated (McDonald, 2007). Thus was Holmes uniquely schooled in the German tradition by Edinger and the British by Jackson. Notable research produced around the time included a description of familial cerebellar degeneration in 1908, and, with Thomas Grainger Stewart, a characterisation of the clinical signs of cerebellar dysfunction resulting from their observations of 40 patients with cerebellar tumours (Fine et al., 2011).

Cometh the hour

At the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914, Holmes applied for a com- mission in the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) but was initially rejected due to his myopia. Unabashed, he volunteered with Percy Sergeant, another Surgeon from Queen Square for duty in a Red Cross Hospital just behind the front line. Their success here led to the RAMC reconsidering their decision and he was appointed as consultant neurologist to the British Armies in France. Harvey Cushing describes his tireless work with patients after the Battle of Ypres and Passchendaele thus; “There are 900 acutely ill soldiers, convoys of 300 wounded might arrive in a day, and there were only 10 doctors” (Lepore, 1994). After long days caring for them, Holmes would go back at night to write up his notes and examine them in more detail, sometimes going as far as to conduct bedside visual field tests (Fishman, 1997).

Thus set the stage for a remarkable body of work on the physiology, anatomy and pathophysiology of the cerebellum and visual cortex. A confluence of events and talents led directly and indirectly to some of the most important scientific and clinical advances of the 20th century.

Firstly, the Brodie helmet used by the British on the Western front was designed to be easily and cheaply produced from a single stamping of metal (Shadrake and Pugh, 2014), and provided good protection from airburst shells but not from shrapnel rounds that burst closer to ground level. In this case, occipital lobe and cerebellar damage resulted because “British helmets danced on top of their heads, unlike those of the Germans” (Fig.3, Fishman, 1997).

Secondly, the introduction of new, more powerful rifles in the late 1800s imparted enough velocity to allow a projectile to enter the skull and cause limited and discrete damage, but not so much velocity as to produce the cavitation and extensive shockwave damage that modern weapons do. As Holmes himself described in his 1917 article on cerebellar lesions, “The opportunity of making uncomplicated clinical observations is rare in civil life, since acute lesions of the cerebellum, comparable with those produced by physiologists, are uncommon; tumours and abscesses which develop in it are very liable to compress or influence the functions of other parts too…… In warfare, on the other hand, wounds limited to the cerebellum and injuries of it of different extent and localization, can be frequently observed” (Holmes, 1917).

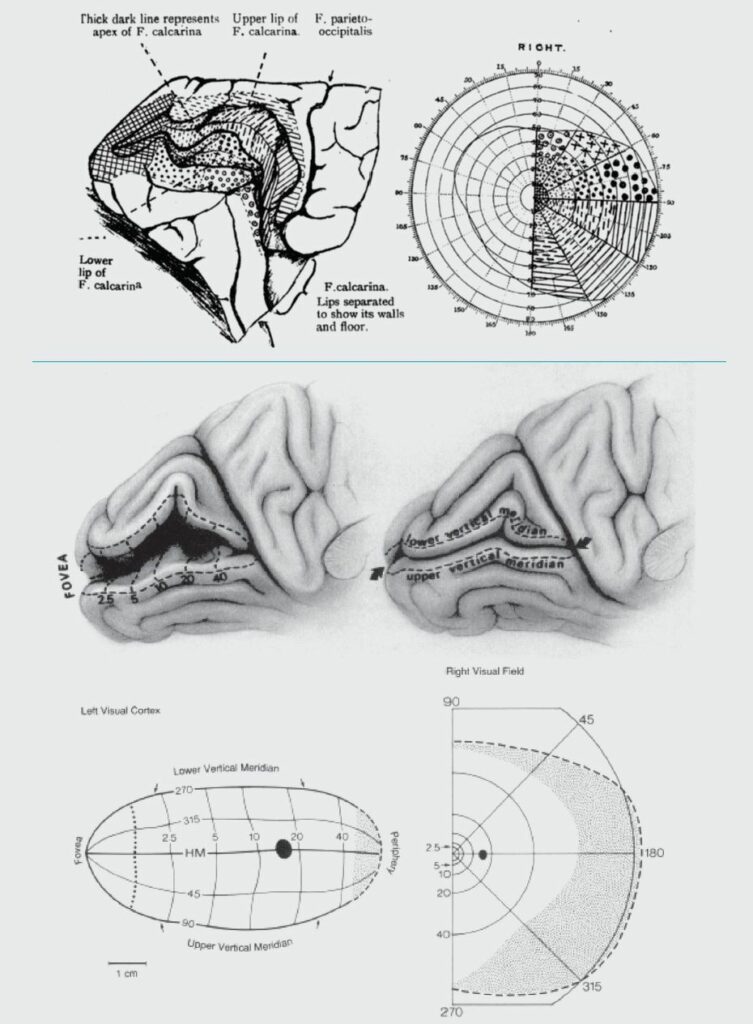

Thirdly, Holmes had rigorous training in anatomy, physiology and clinical observation. This uniquely disposed him to the characterisation and mapping of visual field loss due to discrete lesions of the occipital lobe. His extensive pre-war experience in measuring functional loss (movement dysmetria, decomposition and loss of recoil) due to cerebellar tumours (Stewart and Holmes, 1904) was also invaluable when studying the large cerebellar lesions consequent to shrapnel and bullet wounds. Holmes’ initial maps of visual field localisation (Holmes, 1918) survived almost unaltered until Horton and Hoyt’s (1991) revision of this map using magnetic resonance imaging (Fig.4). His description of the clinical signs of cerebellar damage (ataxia, dysmetria, movement decomposition, tremor, hypotonia, nystagmus) provided comprehensive tools by which clinicians could characterise and quantify loss of cerebellar function (Holmes, 1917), tools still very much in use today.

Intersections and perspectives

To the Irish medical educator, Holmes’s contribution to the body of knowledge on neuroscience is a source of great pride. From a UK perspective, there is gratitude for his insistence on front line duty and tireless service to the injured “Tommy” on the Western front. Expanding to a European point of view, Holmes can be seen as a great inheritor of both the German and British neuroscience traditions who used his pan-European back- ground to push the boundaries of the field. Further afield, as editor of Brain from 1922 to 1937, he influenced the science worldwide.

Wilder Penfield (who studied under notables such as Ramon y Cajal and CS Sherrington amongst others, opined that Holmes was “one of the finest teachers he had known; beneath the exterior of a martinet, there was an Irish heart of gold” (Breathnach, 1975). His legacy has relevance for modern educational interdisciplinarity, combining, as it did, excellence in visual art, anatomy, physiology, pathology and clinical skills. His life and work makes the case for the non-siloed, interdisciplinary thinking beloved of future educational planners.

Acknowledgements

Dr Stanley Hawkins Consultant Neurologist (Retired, formerly QUB School of Medicine Dentistry and Bio- medical Science) was of great assistance and encouragement in the preparation of this article.

References

Breathnach C (1975). Sir Gordon Holmes. Medical History 19(2), 194-200. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025727300020147

Fine EJ et al., (2011). Neurognostics answer. Journal of the History of the Neurosciences 20,170–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/0964704X.2011.560826

Fishman RS (1997). Gordon Holmes, the cortical retina, and the wounds of war. Documenta Ophthalmologica 93, 9–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02569044

Holmes GM (1901). The nervous system of the dog without a forebrain. The Journal of Physiology 27(1- 2), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.1901.sp000855

Holmes G (1917) The symptoms of acute cerebellar injuries due to gunshot injuries. Brain 40(4), 461–535. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/40.4.461

Holmes G (1918). Disturbances of vision by cerebral lesions. British Journal of Ophthalmology 2(7), 353-384. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.2.7.353

Horton JC, Hoyt WF (1991). The representation of the visual field in human striate cortex: a revision of the classic Holmes map. Archives of Ophthalmology 109(6), 816–824. https://doi.org/10.1001/ar-chopht.1991.01080060080030

Lepore FE (1994). Harvey Cushing, Gordon Holmes, and the neurological lessons of World War I. Archives of Neurology 51(7), 711–722. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneur.1994.00540190095022

McDonald I (2007). Gordon Holmes lecture: Gordon Holmes and the neurological heritage. Brain 130(1), 288–298. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awl335

Shadrake D, Evans-Pughe C (2014). Putting a lid on it [First World War Equipment Design]. Engineering & Technology 9(6), 44-47. https://doi.org/10.1049/et.2014.0603

Stewart TG, Holmes G (1904). Symptomology of cerebellar tumours. Brain 27, 522-592. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/27.4.522