Physiology News Magazine

Sixtieth anniversary of the famous Mount Everest ascent

News and Views

Sixtieth anniversary of the famous Mount Everest ascent

News and Views

Austin Elliot

University of Manchester

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.93.10

The Physiological Society Meeting at the National Hospital, Queen Square, on 18–19 December 1953 featured three Saturday morning demonstrations of equipment used on the famous Mount Everest ascent earlier that year, all by people associated with the expedition in different ways (see J Physiol vol. 123, 24P–26P). Three of the four authors – R B Bourdillon, J E Cotes and L G C E (Griff) Pugh – were career employees of the MRC and were, or became, Phys Soc Members. Two – T D (Tom) Bourdillon and Griff Pugh – had been members of the Everest expedition.

Robert (R B) Bourdillon (1889–1971) was a distinguished medical researcher, trained in medicine and physical chemistry and best-known for his work on vitamin D in the 1920s and ‘30s. A keen climber in his youth, from the late 1940s he directed the MRC Electro Medical Research Unit at Stoke Mandeville Hospital, which developed medical devices. His elder son Tom (T D) Bourdillon (1924–1956) was a leading climber and mountaineer of the immediate post-WW2 era, and a physicist working in rocket propulsion research. The Bourdillons were keen advocates for ‘closed-circuit’ oxygen sets – self-contained breathing apparatus, modelled on that devised for fire-fighting and mine rescue work.

Bourdillon senior’s interest in the problems of hypoxia in high-altitude climbing was instrumental in persuading the ‘Himalayan Committee’ to send a physiologist on the 1952 expedition to the Himalayan mountain Cho Oyu, where the hope was that many of the logistical and physiological problems for an Everest attempt the following year could be worked out. Bourdillon suggested that Griff Pugh, who he knew of via the MRC, would be a suitable candidate due to Pugh’s experience in the mountains. It was to prove a fortunate (inspired?) suggestion.

Pugh (1909–1994), then recently appointed to the National Institute for Medical Research in Hampstead, was a believer throughout his career in field research on small groups of trained or elite subjects – often with himself as subject or control, depending on the experiment. On the 1952 Cho Oyu expedition he set about systematically addressing the outstanding physiological questions, using the climbers and their sherpas as his subjects. Pugh was the first to make realistic empirically based estimates of the precise rate of O2 delivery that would be required for strenuous climbing at high altitude. Another key insight that was to pay dividends the following year was that fluid loss (mostly via increased respiration) was a major concern. Pugh set down calorie and dietary requirements, and recognised the importance of the climbers’ sleep and recovery for their ability to maintain conditioning. All his recommendations, summarised in a famous (though unpublished) report, were to prove critical for the successful 1953 Everest ascent.

Pugh continued his researches at altitude as a member of the Everest expedition, though the climbers did not always prove the most willing subjects. Following the expedition Pugh was overwhelmed with juggling post-expedition commitments – attending functions and giving large numbers of seminars through the latter part of 1953 and 1954 – and trying to pick up the threads of his earlier research on survival in cold water. As a result the appearance of his Cho Oyu and Everest data was delayed, with the papers not appearing in J Physiol until 1957 and 1958. They contain much of interest, including measurements on both the Everest ‘summiteers’ Ed Hillary and Tenzing Norgay.

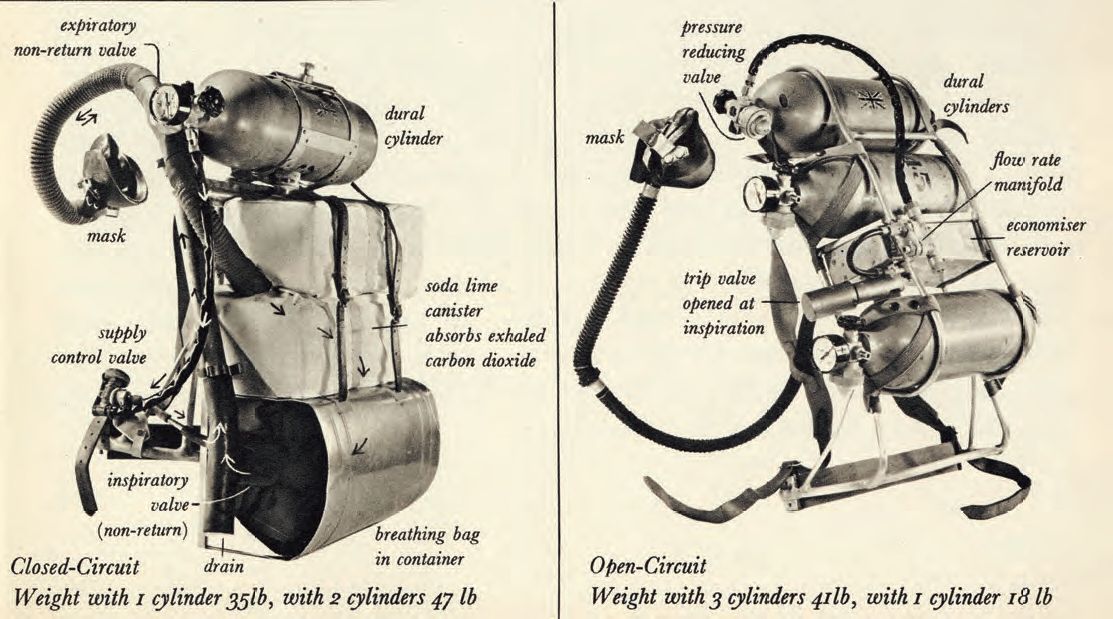

The 1953 expedition took along both ‘closed-circuit’ and ‘open-circuit’ oxygen equipment. The former was widely agreed to be the ideal solution if it could be made to work reliably at altitude, though only the Bourdillons believed it could. The closed circuit system closely resembles the classic undergraduate physiology experiment of re-breathing from an O2-filled spirometer, with exhaled CO2 removed by absorbing it with soda-lime (‘an extended period of normal breathing’). This system delivered close to 100% O2 to the climber, and also greatly reduced respiratory fluid loss. However, the closed-circuit sets proved temperamental and unreliable in the mountains. Tom Bourdillon and Charles Evans were forced to abandon their summit attempt using them when one of the sets malfunctioned still 300 ft, and 2 hours climbing, short of the peak.

Hillary and Tenzing, in their successful summit attempt 3 days later, used the technically simpler and more robust open-circuit oxygen equipment. This was derived from wartime RAF oxygen equipment, but had been modifed by John E Cotes, who worked at the MRC’s Pneumoconiosis unit in Cardiff. The modifications reduced resistance to airflow in the apparatus – vital when a climber’s lungs might be moving 100 litres a minute – and also adapted the masks to avoid the valves freezing in the sub-zero air. The rates of O2 delivery were based on Griff Pugh’s research.

Of the December 1953 authors, John Cotes, then only in his 20s, went on to a long and distinguished career in respiratory medicine and research – including authoring one of the definitive textbooks on lung function, now in its sixth edition. R B Bourdillon retired in 1955, moving to British Columbia where he took an interest in early years education. Tragically, Tom Bourdillon was killed in a climbing accident in Switzerland in 1956. Griff Pugh, finally, has got his due as a pioneer of applied physiology with a wonderful biography written by his daughter Harriet Tuckey (see review later in this issue).