Physiology News Magazine

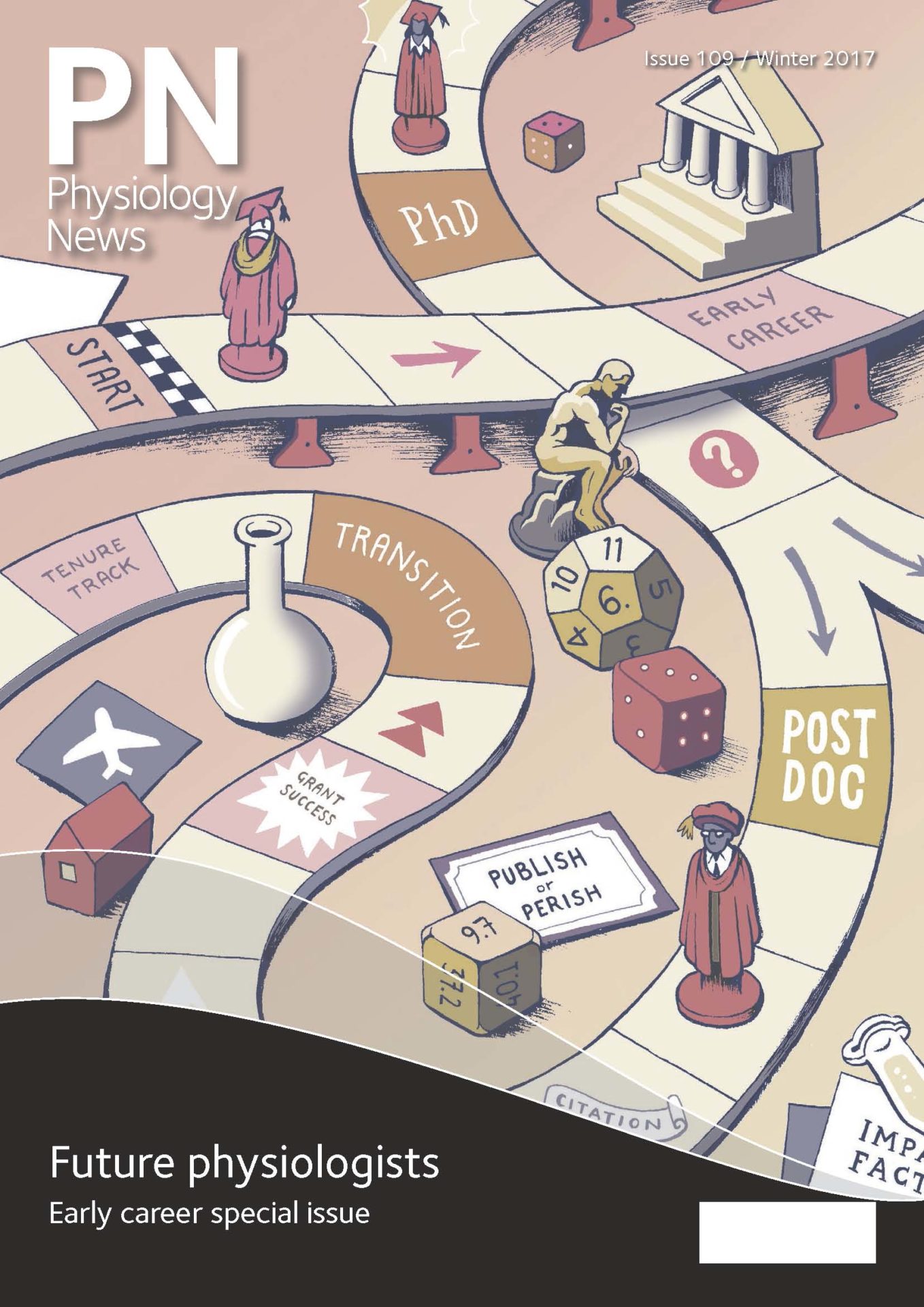

The postdoc problem

To be in academia, or not to be in academia?

Features

The postdoc problem

To be in academia, or not to be in academia?

Features

Hannah Marie Kirton

Cardiovascular Research Fellow, University of Leeds, UK

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.109.36

Postdoctoral scholar: an individual with a doctoral degree engaged in mentored research or scholarly training; both instrumental in acquiring the professional skills needed for independence and leadership.

Worldwide, the number of PhD’s and postdocs is outpacing the number of permanent senior academic positions. From 1999 to 2003 alone, there was a 31% increase in the number of PhDs. Several decades ago, most PhD’s ‘walked’ into permanent academic positions upon completion of their PhD. But as the doctorate numbers rise, most find themselves funnelled into the world of the postdoc, with only a small percentage making it to permanent academic positions. Statistics in the U.K alone show that 19% of doctorates are employed in any academic job, but only 3.5% enter into permanent academic positions. And if you think escaping to America will improve your odds, Andrew Hacker and Claudia Dreifus reported that between 2005-2009 more than 100,000 doctoral degrees were awarded in the USA. In the same period, there were only 16,000 new professorships.

We face the challenge to cure major diseases – Alzheimer’s, heart failure, cancer – and yet, academic institutions are faced with a crisis of declining funds. This is driving PI’s to fire lab technicians, increasing the burden on the postdocs. Furthermore, fellowship success rates have reduced (from around 50% to 3-5% quoted for today’s prestigious fellowships). Further still, the postdoc lifestyle brings pressures: to maximise publications, impact factor and citation rates, achieve independent funding success, and to mentor and teach. We face a burdensome work environment often working at multiple institutions with heavy workloads, playing havoc with any chance of a work-life balance. We are a cheap, highly motivated, disposable source of labour that boosts an institution’s research capacity. Yet there is clearly a struggle to achieve higher academic status, which forces an ever-increasing number of talented early career researchers to question their next career move. It is therefore not so surprising we see PhDs and postdocs, the driving force of cutting-edge research, taking a swift exit from academia in the pursuit for other professions.

Permadocs, Superdocs …Independence!

How do we correct the ‘Postdoc Problem’? And how do we break through the barrier to climb the academic ladder? In some countries, including the UK, governments are encouraging permanent postdoc positions, and limiting the number of years postdocs remain on short-term contracts. Some institutions, particularly in the US, are introducing senior postdoc positions – the superdocs. Such positions, created for talented postdocs who may have no desire to start their own labs, are classified as permanent senior staff scientists on higher paid wages. Superdocs can take on the role of a lab manager. They can conduct the science they love, while assisting in publication writing, mentoring trainees and advancing current technology, without the pressure of being the PI.

But many postdocs want to continue in academic research and are willing to endure the pressures of Brexit and the postdoc burden for a chance of becoming PI. And in doing so they are willing to fight and break through to independence for a tenured or full time academic staff position. And many are achieving this, with the help of external societies and university institutes lifting limitations and broadening the boundary for success, respectively. This is helping us diversify our approach to success and ease the burden of being an early career researcher.

If you, like many postdocs, are stuck as a so-called ‘permadoc’ – one who has fulfilled more than six years of postdoc experience – there are still ways to climb the academic ladder. For example, most societies and funding agencies have lifted the age restriction for fellowships. This not only secures research excellence in our society, but also enables senior postdocs to push for independence in a time of funding limitations. Funding bodies now also fully support applicants returning to research following a career break.

In addition to this, most learned societies and organisations, including The Physiological Society, support the pursuit of independence in the early stages of academia. This includes outreach funds, travel grants and vacation studentships to support summer students on a project piloted by an early career researcher. Collectively each of these awards allow Society members to promote their independent funding success and leadership. The Physiological Society also support early career conferences and other networking opportunities, physiologists in their first permanent academic position, and those returning to a permanent position after a career break.

What do we want and when do we want it?

Career Action Plan

Although we are increasing our profiles with glamourous funding and leadership skills or substituting our desired goal for a permadoc position, three-quarters of us still end up outside academia.

To retain talented early career researchers, we need to nurture new PhD’s and postdocs through ‘career action plans’. Firstly, we need to be honest and advise PhD’s and postdocs about the ‘ugly truth’ of academia, and if needed, to take a realistic view early in their career path. This could come in the form of an institutional induction to highlight their rights, entitlements, and responsibilities in academia. In this manner, they have an understanding of what they can hope to achieve, and most importantly what actions to take to get there. This in turn warrants regular reviews on their progress, and an expectation for our institutions to demonstrate talent retention in the form of fellowships.

Mentoring and Postdoc Champions

Mentorship is also key, and can be sought through internal or external opportunities (including The Physiological Society). Mentor circles within institutes can also be particularly useful, enabling postdocs to interact and share their journeys. Institutional support is fragmented at best and often relies on word of mouth from one postdoc to another. Therefore a ‘postdoc champion’ – a permanent staff member aware of the needs of postdocs and how best to address them – within our Faculties and Schools could transmit a wealth of key and current knowledge to early career researchers.

A step down fellowship lane

Even with better action plans and mentoring, lack of funding remains an impediment at all levels of academia. Improvements are necessary at the institutional and research council level. We suggest institutions in receipt of funding for PhD and postdoctoral researchers should be expected to sign the Concordat on Early Career researchers. In addition, they should be required to demonstrate how they meet, or are working towards these recommendations.

To help with funding success, postdocs should be allowed full co-applicant status on grants; this would enable postdocs to develop their own research themes and move towards independence. Furthermore, postdocs are currently allowed time for teaching and clinical work. Why not build in time for research development and career progression? As Janet Metcalfe, Chair and Head of Research Career Development Organisation states, ‘while funding from research councils to support postdocs are often attached with guidelines emphasising the importance of career development for the researchers, these expectations seldom translate into practice.’

In essence, never give up! There are diverse ways to pursue independence and encourage new interventions that help recognise and retain early career talent in academia.

This article was edited by Jo Edward Lewis.