Physiology News Magazine

The science and art of detecting data manipulation and fraud: An interview with Elisabeth Bik

News and Views

The science and art of detecting data manipulation and fraud: An interview with Elisabeth Bik

News and Views

Julia Turan, Managing Editor, Physiology News

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.118.10

How big of a problem is data manipulation and fraud in biomedical science?

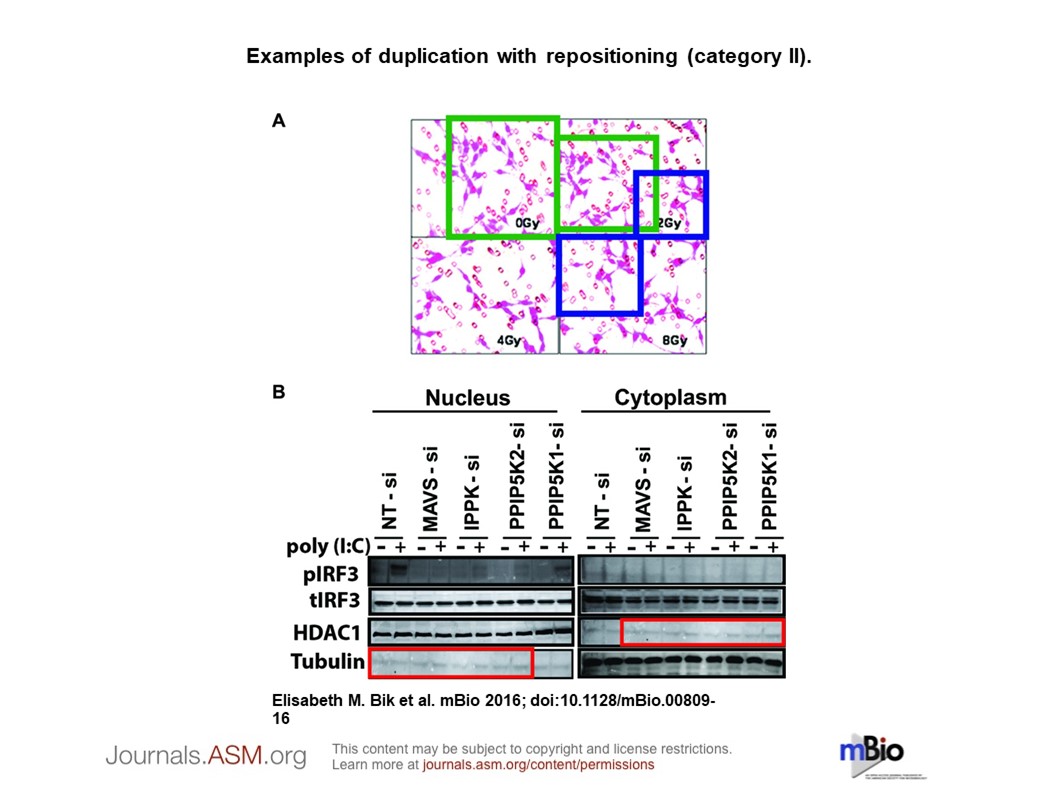

It is hard to make a good estimate about the percentage of papers with manipulated data. In my search of 20,000 biomedical papers that contained western blots (photos of protein gels stained with an antibody to analyse that protein’s expression) I detected image duplication in about 4% of the papers.1 Some of those duplications could be simple errors, but about half of those papers contained shifted, rotated, mirrored, or manipulated duplicates, which are more suggestive of an intention to mislead. So based on that study, we might conclude that 2% of those papers might contain intentionally duplicated photos. But the percentage of manipulated data, so not just looking at photos but also considering tables and line graphs, might be much higher. It is very hard to detect falsified or fabricated data in a table unless you compare the original lab book notes to the published data. Therefore the true percentage of data manipulation is probably much higher than 2%.

Which data are prone to the most manipulation/fraud?

All data. For me, it is easiest to detect duplications in photos, but I sometimes find unrealistic data in tables as well. For example, I found tables in which the standard deviation of dozens of values was always around 10% of the mean value they represent. That is not realistic for biological data, which is usually much more variable.

How, if at all, are journals/institutes/governments dealing with it?

Most journals that are part of the large scientific publishing houses scan for plagiarism, which is a form of research misconduct. Several journals, such as Nature, PLOS One, and Journal of Cell Biology, have recently implemented more strict guidelines for photographic figures, such as specifically prohibiting cloning, stamping, splicing, etc. And some journals are starting to better scrutinise images in manuscripts sent to them for peer review, as well as asking authors to provide raw data.

Institutes have not been very responsive to allegations of misconduct. Most institutes in the US will provide some classes on misconduct, but when it comes to actually responding and acting upon whistleblowers’ reports, they tend to underperform. Most of the misconduct cases are swept under the rug and, very often, the whistleblower is the one who is fired, not the person accused of the misconduct. Kansas State University ecologist, Joseph Craine, and Johns Hopkins University statistician, Daniel Yuan, were both fired for being whistleblowers,2,3 while Eleni Liapi of Maastricht University lost access to her lab and servers before being asked to quit,4 and Karl-Henrik Grinnemo’s career was severely damaged.5

What is an image duplication detective and how did you get into it?

I started this work around 2014, when I investigated a PhD thesis with plagiarised text in which, coincidentally, I spotted a duplicated western blot. I realised that this might also happen in published science papers, so I started scanning papers that very evening. Immediately, I found some other cases, and I was fascinated and shocked at the same time. Since then, I have scanned 20,000 papers in a structured way, so from different journals, different publishers, and different years. After the publication of our 2016 mBio paper together with Ferric Fang and Arturo Casadevall,1 I kept on doing this work. About a year ago, I left my paid job to do this work full time.

There are several ways I scan papers, but I mostly follow up on leads that other people send me (“Can you please check the papers by Prof. X because we all suspect misconduct?”) or on groups of papers from the same authors that I found earlier. Image misconduct appears to cluster around certain persons or even institutes.

What has been the reception to these activities in terms of resistance or support from the community and powers that be?

The reception has not been very warm, as you might imagine. Journal editors were possibly embarrassed and perhaps even overwhelmed when I started to send them dozens of cases of papers with duplicated images. Over half of the cases I sent to them in 2014 and 2015 have not been addressed at all, which has been frustrating. Some editors refused to respond to me and others have told me that they did not see any problems with those papers.

Institutes to which I reported sets of papers by the same author(s) have mostly been silent as well. But in the last couple of years, the tide has been changing, and I am starting to see more and more journal editors who are supportive and are actively trying to reject manuscripts with image duplications, before they are published.

How do you detect image manipulation, and are there resources to help automate detection or learn how to do it?

I scan purely by eye. Having scanned probably over 50,000 papers by now, I have some experience on which types of duplications or manipulations to look out for. For complicated figures with lots of microscopy panels I use Forensically6 but that can only detect direct copies, not anything that has been rotated or zoomed in/out. There is no good software on the market yet to screen for these duplications, but there are several groups working on automated approaches, with promising results.7,8,9

What are some of the most common types of manipulations? How are these done?

The most common ones are overlapping microscopy images. These are two photos that represent two different experiments, but that actually show an area of overlap, suggesting they are the same tissue. Another very common type is western blots that are shifted or rotated to represent two different experiments. These two examples are not photoshopped, but manipulated in the sense that the photos are somewhat changed (shifted, mirrored, rotated) to mislead the reader. True photoshopped images, where parts of photos are cloned or copy/pasted into other photos are quite common among flow cytometry images.

How have social media and crowdsourcing helped in this endeavour (i.e. Twitter, or your blogs Microbiome digest and Science Integrity Digest, etc.)?

They are helping in making people better peer reviewers, and more critical readers of scientific papers. I use Twitter to show examples of duplications, so people are more aware of them, and can find these cases in the future. PubPeer.com is a website where individual papers can be discussed and flagged for all kinds of concerns. ScienceIntegrityDigest.com is meant for more reflective blog posts, or to describe patterns among scientific papers that cannot be spotted by looking at individual papers, such as the paper mill of over 400 papers that we recently discovered.10

What are your hopes for the future of image duplication, manipulation and fraud detection and handling as a community?

There will always be dishonest people, and photoshopping techniques are getting better and better, so it is unrealistic to think we can catch all of these cases during peer review, even with detection software. But I hope we can take some of the pressure off scientists that feel driven to publish at any cost. Scientific papers are the foundation of science, but it is unrealistic to ask graduate students, postdocs and assistant professors to publish X number of papers with a combined impact factor of Y before they can graduate or get tenure. Good science takes time, often fails, and never keeps to imposed deadlines. If we measure good science by the wrong output parameters, we put too much temptation onto people to cheat.

What is next for you and how do people keep track of your fascinating activities?

I am not sure yet! I have so many interesting leads to follow that I will probably be busy uncovering “clusters” of misconduct for the next couple of years. But I also hope I will be less regarded as a pair of extraordinary eyes with a Twitter account, and more as a real scientist who wants to improve science. I hope there will be a place at the table for me with institutes and publishers to talk about better ways to detect and decrease science misconduct. You can always follow me on Twitter at @MicrobiomDigest.

References

- Bik EM et al. (2016). mBio 7(3), e00809-16. DOI:10.1128/mBio.00809-16

- Han AP (2017a). Ecologist loses appeal for whistleblower protection. [Online] Retraction Watch. Available at: retractionwatch.com/2017/05/05/ ecologist-loses-appeal-whistleblower-protection/ [Accessed 17 May 2020].

- Han AP (2017b). Would-be Johns Hopkins whistleblower loses appeal in case involving Nature retraction. [Online] Retraction Watch. Available at: retractionwatch.com/2017/05/25/johns-hopkins-whistleblower-loses-appeal-case-involving-nature-retraction/ [Accessed 17 May 2020].

- Degens W (2020). Maastricht professor of Cardiology accused of academic fraud. [Online] Observant. Available at: www.observantonline.nl/Home/Artikelen/ articleType/ArticleView/articleId/17817/Maastricht-professor-of-Cardiology-accused-of-academic-fraud [Accessed 17 March 2020].

- Herold E (2018). A star surgeon left a trail of dead patients–and his whistleblowers were punished. [Online] Available at: leapsmag.com/a-star-surgeon-left-a-trail-of-dead-patients-and-his-whistleblowers-were-punished/ [Accessed 17 March 2020].

- Wagner J (2015). Forensically, Photo Forensics for the Web. [Online] ch. Available at: 29a.ch/2015/08/16/ forensically-photo-forensics-for-the-web [Accessed 17 March 2020].

- Acuna DE et al. (2018). Bioscience-scale automated detection of figure element reuse. [Preprint] DOI: 10.1101/269415

- Bucci EM (2018). Automatic detection of image manipulations in the biomedical literature. Cell Death & Disease 9, 400. DOI: 10.1038/s41419-018-0430-3

- Cicconet M et al. (2018). Image Forensics: Detecting duplication of scientific images with manipulation-invariant image similarity. [Preprint] arXiv:1802.06515

- Bik EM (2020). The Tadpole Paper Mill. [Online] Science Integrity Digest. Available at: scienceintegritydigest.com/2020/02/21/the-tadpole-paper-mill/ [Accessed 6 May 2020].