Physiology News Magazine

The Society’s winter party & AV Hill’s Nobel Prize

News and Views

The Society’s winter party & AV Hill’s Nobel Prize

News and Views

David Miller

Former Chair, History & Archives Committee & Honorary Research Fellow, University of Glasgow, UK

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.106.12

The Society’s informal Winter Reception was held at Hodgkin Huxley House (H3) on 1 December 2016. This was an opportunity to meet members of AV Hill’s family as his Nobel Prize Diploma was formally received as a gift from them to The Society. We were delighted to welcome several of AV’s grandchildren (Julia Riley, Nicholas Humphrey and his wife, Ayla, Charlotte Humphrey, Alison Hill, James Hill and Griselda Hill attended) plus a great granddaughter (Jenny Hill). The President, David Eisner, spoke to welcome the many Society members who attended as well as to thank the Hill family for their generous gift. Dr Julia Riley (Girton College and the Cavendish Laboratory, Cambridge) gave a charming and entertaining speech with anecdotes of dinghy capsizes and multiple pet tortoises amongst cherished memories of her and the other grandchildren’s frequent visits to AV’s Hampstead home and of shared holidays.

At the age of just 36, AV Hill (1886-1977) was awarded the Nobel Prize ‘for Physiology or Medicine’ for 1922, shared with Otto Meyerhoff. An unusual twist is that the prize had not been awarded in 1922 and thus two prizes were awarded in 1923. (Banting and Macleod shared the ‘1923’ Prize ‘for the discovery of insulin’). Hill’s Nobel citation was for ‘his discovery relating to the production of heat in muscle’. This and his subsequent work relating to electrically excitable cells and to muscle function are foundations of the discipline now termed biophysics. In parallel with his research, AV’s life-long humanitarian, science-administrative and collegiate work is also of unprecedented quality. Members unfamiliar with the great man will be richly rewarded if they read any of the biographical reports on AV (e.g. Katz, 1978, Vrbová, 2013).

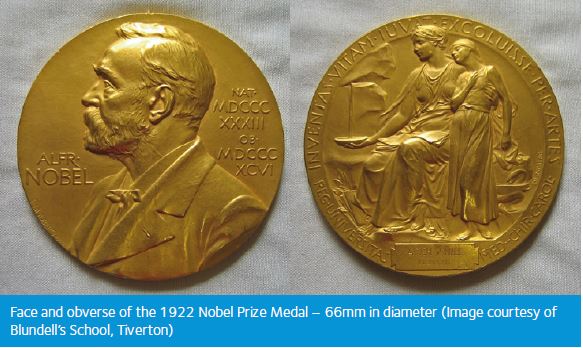

The ornate and unique Nobel Diploma is held in a beautifully crafted leather folder. The artwork for all the Physiology or Medicine Prize diplomas from 1919 to 1927 was by Anna Berglund. These valuable items will be securely housed in The Society’s archive at the Wellcome Library. A high-quality facsimile will be prominently displayed at H3, where one of the meeting rooms is already named after AV. The Nobel Medal is held by AV’s former school, Blundell’s, in Devon. A final charming artefact that The Society keeps at H3 comprises AV’s dissection spectacles, together with those of his student, fellow Nobel Prize winner and one-time lodger, Bernard Katz.

The following talks were given on the occasion of the presentation to the Society of AV Hill’s Nobel Prize certificate:

The Physiological Society’s President, David Eisner, on accepting the Nobel certificate

It is nice to see many of our members here, in particular those from our very active History and Archives Committee for whom today is a special day. I would also like to greet the representatives of our sister societies and those other groups we interact with. There is no doubt that, particularly in these challenging times, those of us who wish to see science flourish need to stick together.

The Physiological Society was founded in 1876. We are therefore very pleased to be celebrating our 140th birthday this year. During this time several members have been awarded a Nobel Prize. We are here to celebrate one of these, Archibald Vivian Hill (always known as AV) who was born in 1886 when The Society was just 10 years old. The guests of honour here are therefore the members of the Hill family who have generously donated AV Hill’s Nobel Certificate to The Society. We have the pleasure of welcoming several of his grandchildren and one great granddaughter. I won’t embarrass them by listing all their achievements but they include astrophysics, psychology, sociology, medicine and pottery. In a few minutes the family will hand over the certificate. Before that, I would like to spend a couple of minutes reminding you about the debt we owe to AV Hill and why we are so excited to have received this certificate.

AV Hill made massive scientific contributions. The eponymous Hill Equation is still used to report on interactions and cooperativity of binding. This work was published in 1910 as a communication to our Society. A year earlier he had analysed the time-course of muscle contraction produced by nicotine and concluded that this reflected ‘a gradual combination of the drug with some constituent of the muscle’. This must be one of the earliest mentions of what we now call a receptor for a drug. His Nobel Prize was awarded for his elegant studies on the relationship between muscle heat and contraction and work. He developed incredibly precise methods to measure the heat generation and showed that the initial contraction did not require oxidative metabolism. He demonstrated that oxygen is required during recovery from contraction. This oxygen debt is noticed on recovery after sprinting, for example.

His scientific achievements alone would be sufficient to celebrate him but he is equally well known as a humanitarian. He was awarded the Nobel prize in 1923 together with the German, Otto Fritz Meyerhof. This was only 4 years after the end of the very bloody First World War. In his Nobel speech he said, ‘The War tore asunder two parts of the world as essential to one another as man and wife. Physiology, I am glad to know, was the first science to forget the hatreds and follies of the War and to revive a truly international Congress: my own country, I am proud to boast, was happy to be its meeting ground. For a while, my friend Meyerhof was an enemy: today he is again a colleague and a friend’. The mention of a ‘truly international Congress’ is significant. The previous international meeting had been held in Paris in 1920 but was restricted to scientists from allied and neutral countries. AV Hill had objected to this and was delighted when the 1923 meeting, held in Edinburgh, was open to all. One might note that he was ahead of his time as the invitation to German scientists to participate meant that many French scientists declined.

Much later, during the Second World War, he said, ‘It may be then that through this by-product of international cooperation science may do as great a service to society (just as learning did in the Middle ages) as by any direct results in improving knowledge and controlling natural forces: not – as I would emphasise again – from any special virtue which we scientists have, but because in science world society can see a model of international cooperation carried on not merely for idealistic reasons but because it is the obvious and necessary basis of any system that is to work’.

Although, it would be an exaggeration to compare Brexit with the situation that Hill was commenting on, the idea that science both requires international cooperation and can bind people together should not be forgotten.

Hill, the humanitarian, is best known for his work in helping the scientific victims of Nazi persecution. Together with Ernest Rutherford and William Beveridge, in 1933 he established the Academic Assistance Council, which was set up to meet this need. It is worth noting that, this was at a time when the events in Germany were not known to the majority of people in the UK. This organisation helped 1000 scientists escape including many members of The Physiological Society. Not only did his foresight saved these individuals but it energised British Science with some wonderful individuals. One thinks of Bernard Katz, Hans Krebs, and Edith Bulbring to name but three.

I could go on at greater length but I hope I have said enough to remind you that AV Hill was one of the towering figures of the 20th Century. I will end simply by welcoming the Hill Family again and thanking them, on behalf of The Physiological Society, for this most generous donation of AV’s Nobel certificate.

Katz B (1978). Biog Memoirs Fellows Roy Soc 24, 71-149

Vrbová G (2013). Eur J Trans Myology 23 (3), 73-76

My grandfather, AV Hill: by Julia Riley (née Hill)

Our grandfather AV, known to us all as Grandpa, was much loved by his grandchildren. There were 14 of us – and also one step-grandchild and two honorary grandchildren. From an early age we appreciated him as someone who was able to do things for us and with us that really intrigued us. He always had time for us, and we will all have regarded him as very approachable and very understanding of the way children operated. Obviously as we grew older we all came to know that Grandpa was a hugely distinguished man, and I am sure I can speak for us all in saying we are very proud to be his grandchildren. In return we knew he was very proud of us in all our varying ways and greatly enjoyed and valued our company.

Our family visited our grandparents at their house, Hurstbourne in Highgate, maybe every couple of months, staying for lunch and tea and usually meeting up with the London cousins for one or other of the meals. One of my brother Mark’s memories of him there is that he had an enormous love of mechanical calculating machines, encouraging the young to make daring calculations such as an approximation to the square root of 2. Mark also recalls our fascination with the fact that he took snuff – this was for the simple reason that in his time as an MP it had been available free and he thought he should take advantage of this facility! We all remember the wonderful garden at Hurstbourne – among other things there was an aviary with parakeets (which escaped) and at least four tortoises. To stop the tortoises from escaping into the neighbouring gardens, Grandpa’s solution was to link a pair together with a long piece of string, each end of which was tied through the back edge of the shells of the tortoises so that they did not get very far.

There were the family holidays as well. Grandpa had a great love of Devon (from his schooldays at Blundells School near Tiverton); he and my grandmother (who we all called Gran) had a family holiday house near Ivybridge called Three Corners. We stayed there on occasion, enjoying lovely walks through the wood called Hawns and Dendles with its tumbling stream running down through a beautiful oak-beech wood, and exciting walks on Dartmoor. We visited the beach at Mothecombe where we collected winkles which we cooked and ate with a pin; I recall the journey home in which at some point at the top of a hill some distance away the driver of the car would switch off the engine and aim to get back to Three Corners by free-wheeling the whole way.

When we reached a certain age, the older ones amongst us were taken one or two at a time by Grandpa for a special visit to Plymouth – Grandpa had many colleagues in the Marine Biological Association Laboratory and loved visiting them to talk about science but also wanted to show his grandchildren the things he loved about Plymouth. My sister Alison and I remember being driven down to Plymouth by him – singing ‘Are we downhearted noooo!’ (a famous First World War song) at the tops of our voices as we went along; Alison recalls visiting Stonehenge on the way and walking round the stones. We stayed with Grandpa in the Strathmore Hotel on Plymouth Hoe, and amongst other things, visited Eric Denton and his wife (who were great friends of his) and went out in one of the research ships, Sarsia. Both Alison and my brother James ended up working in Plymouth because of the connection with Grandpa – and James has worked in Devon as a GP since he completed his training (I am very pleased that James’s daughter Jenny is here tonight – particularly as she wrote a dissertation on AV and his work with the academic refugee council when she was doing her undergraduate degree in History).

Later on, Gran and Grandpa bought The Hall at Sea Palling in Norfolk as a holiday house; this was a rambling house divided into two halves so that two of the four families could stay there at once, or Gran and Grandpa could stay in one half with one family in the other half. One of the attractions was sailing on Hickling Broads, and our grandparents bought a small sailing dinghy which they kept there. I don’t think sailing was one of Grandpa’s great strengths and I was completely convinced the entire time I was in the boat with him that he would capsize it. In fact he did capsize quite regularly – Alison remembers doing so – and they had to be rescued as they couldn’t right the boat, and she recalls watching her bobble hat sailing away across the Broad; there was another occasion on which he capsized when he decided he needed to save his watch from the water and, in his practical way, took it off and put it in his mouth whilst attempting to right the boat.

Grandpa was a very practical person though he was not himself very dextrous and he greatly admired people who could build things and make things. He was not too much bothered by what things looked like so long as they functioned in the right way – his books were numbered indelibly on the spines as this meant he could find them easily and if they fell apart through use were mended with bright blue tape (several otherwise priceless first editions were treated in this way). He did not collect things and only valued things which were of use to him; if something got broken he would mend it so that it functioned afterwards – but its appearance didn’t matter. I have a large blue and white jug which I got from him which has to spend its time with one side facing the wall because it is covered in a thick and very unbeautiful layer of araldite (but the jug is watertight).

He and our grandmother moved to Cambridge to a large ‘flat’ in our family house in Chaucer Road in 1967 – when Gran who had Parkinson’s could not negotiate the steps at Hurstbourne anymore. He had a large study upstairs which used to be the bedroom I shared with Alison. In Cambridge he and Gran were looked after by the redoubtable Susan Rendell who had, years before, looked after Gran’s parents. We all remember Susan with great affection too, and she was an integral part of our grandparents’ old age. She was particularly good at making immensely sweet puddings. However, as in almost everything, Grandpa had very simple tastes in food and there was nothing he liked more than rice pudding – I think he could have lived on it. Susan baked one almost every day, and he particularly loved the thick burnt skin on the top. When Alison stayed with him and Susan one holiday, Susan baked two puddings every lunch and asked him which one he wanted – he invariably said rice pudding, so Alison had to eat the other one!

Finally, a word about AV’s Nobel Diploma. I am not quite sure how I came to have it, but I think he must have given it to me at some point when he was living in Cambridge. For the past 40 years it has lived in a cupboard in our attic, and to be honest I had completely forgotten we had it until my husband reminded me of it when we were thinking about AV after the celebration of 100 years of the Cambridge Physiological Laboratory. Through meeting David Miller at the Blue Plaque event at Hurstbourne and hearing from him that there was an AV Hill Room at the Physiological Society we realised that this would be an excellent home for the diploma – not tied to any of the universities AV was associated with but obviously associated with his work as a physiologist. We are delighted that it is now in your archive – much more safely looked after than in our damp attic!