Physiology News Magazine

War and peace:

Physiologists during 1914–1919

Features

War and peace:

Physiologists during 1914–1919

Features

Tilli Tansey, Honorary Archivist, The Physiological Society & Emeritus Professor of Medical History and Pharmacology, William Harvey Research Institute, QMUL, UK

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.112.36

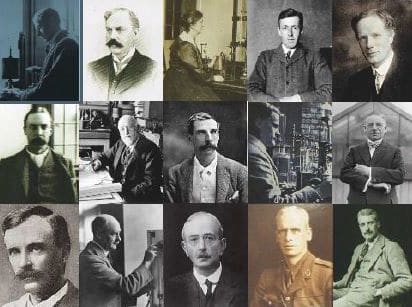

At the 1913 AGM of The Physiological Society, the last before the outbreak of the first World War (WW1), it was noted with approval that membership reached a new peak – 272 – with 16 new Members elected that year. By 1919, however, membership had dropped back to 251. What had happened to British physiologists in the intervening years?

After the outbreak of the WW1 in August 1914, many British physiologists became directly involved with the War effort: some in uniform, some working in areas closely related to their pre-War research, others returning to (or continuing) medical practice, and a few working in completely new fields. Of the latter, two are of especial note; namely, Keith Lucas* (1879-1916, Member 1904) and the future Nobel Laureate A

V Hill* (1886–1977, M 1912). Lucas, a Cambridge neurophysiologist with exceptional mathematical and engineering abilities, was encouraged by Horace Darwin* (1851–1928, M 1881), founder of the Cambridge Scientific Instrument Company and member of the Government’s Aeronautical Research Committee, to join the Royal Aircraft Factory at Farnborough. As a captain in the Royal Flying Corps, Lucas worked on several projects including redesigning aircraft compasses to account for problems caused by engine tremor and the earth’s magnetic field and creating a gyroscopic bomb-aiming device that eliminated vibration error. He was killed in a mid-air collision in October 1916, leaving behind a preliminary draft

of his seminal work Conduction of the nervous impulse. This was completed in 1919 by his student ED (later Lord) Adrian* (1889–1977, M 1917) after his own return to Cambridge. In 1914, Adrian, like many, abandoned the Laboratory for accelerated clinical training, and worked throughout the War on nerve injuries and shell shock at the National Hospital, Queen Square, and the Connaught Military Hospital in Aldershot.

A V Hill had been another of Lucas’ students. Originally a mathematician, he was recruited into the Physiological Laboratory by Walter Morley Fletcher* (1873–1933, M 1898). With the outbreak of War, Hill – a Territorial officer – was quickly invited (again, suggested by Horace Darwin) to create and lead an anti-aircraft experimental section of scientists in what later became known as operational research. Readers wanting to know more about ‘Hill’s Brigands’, some of whose work resulted in the official manuals on anti- aircraft gunnery, are directed to the instructive work of Society Member William van der Kloot.

Physiologists in medicine

Lucas and Hill were unusual in stepping away from physiology. Many Members served in medical and scientific capacities: in hospitals on the battlefield, in military and civilian hospitals on the home front, and as specialist advisers to Government, military and professional committees. It should be emphasised that at this time the majority of Society Members were medically qualified, and a large proportion of those were engaged in clinical practice.

Indicative of this are Members addresses published in the 1905 pre-War Grey Book (the membership list of the Society), the last pre-War volume in the Society’s archives. Such addresses include the Harley Street area of London and similar ‘medical’ areas of other cities (e.g. Rodney Street in Liverpool). Sir Victor Horsley* (1857–1916, M 1884), one of the most distinguished surgeons of his generation, did not live on Harley Street but on Gower Street close to the research laboratory he enjoyed as Professor of Surgery at UCL. He made numerous important discoveries concerning the thyroid gland, and his pioneering work in cerebral localisation included the invention of the first stereotaxic frame. At the outbreak of War, he joined the British Expeditionary Force to the Western Front and later the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force as Colonel and Consultant Surgeon to the British Army. He died of heat stroke near Baghdad in July 1916, a month before the death of Thomas Gregor Brodie* (1866–1916, M 1892). Brodie, an Englishman and then Professor of Physiology at Toronto, was serving with the Canadian Medical Services when he died suddenly of heart failure. The Minutes of the 1916 AGM record ‘The Society has suffered heavily by deaths during the year, having lost three of its most distinguished members, Prof. Brodie, Sir Victor Horsley & Dr Keith Lucas, all of them members by whom much more & valuable work would undoubtedly have been produced’.

Physiologists in physiology

In April 1915, a chlorine attack by the German Army on the Ypres salient on the Western Front marked the beginning of large-scale use of chemical weapons, and many physiologists were recruited to work on the new problems of gas poisoning, prevention and treatment. The Oxford respiratory physiologist JS Haldane* (1860–1936, M 1887) was immediately asked by Lord Kitchener, then Secretary of State for War

(a position held previously by Haldane’s brother Lord [Richard] Haldane who was by then Lord Chancellor) to visit the site and advise the War Office. Haldane subsequently worked, inter alia, on the development of respirators and remained a civilian throughout the War. With similar civilian status, Joseph Barcroft* (1872–1947, M 1900) from Cambridge studied the effects of gas poisoning at the Government’s experimental station at Porton Down, Wiltshire. Barcroft claimed that as a civilian he could be much more assertive to the military top brass. Many of his colleagues, however, were commissioned officers in the RAMC (Royal Army Medical Corps) including Gordon Douglas* (1882–1963, M 1906). Douglas, of the eponymous Bag for respiratory gases, recalled Barcroft on a visit to France proudly demonstrating his status by eschewing a helmet and audaciously wearing his bowler hat within the range of German guns.

The Government’s anti-gas department was established at the RAMC College at Millbank, London under the charge of the Professor of Physiology at UCL, Ernest Starling* (1866–1927, M 1890), then a Major in the RAMC. Like many of his generation, Starling had been immersed in the then dominant scientific culture of Germany. John Henderson’s biography describes him as a ‘man of passion’ with ‘teutonic enthusiasms’, well known

for his deep love of German and Germany. Profoundly distressed by the War, he vowed never to speak German again, becoming quite vociferously anti-German. Indeed, although in his late 40s, he tried to enlist as a combatant before being persuaded that he was more valuable in labs and on committees.

His brother-in-law and frequent collaborator William Bayliss* (1860–1924, M 1890) also diverted into War-related activities, but as a civilian. His lack of a uniform had one unfortunate consequence in 1917 when on a visit to France he became separated from his official host, was arrested, and held briefly as a spy. During that same visit he met the American physiologist Walter Cannon* (1871–1945, HonM 1934), Professor of Physiology at Harvard, then serving as a captain in the US Army Medical Corps. Bayliss’ principal contribution was his work on wound shock, partly in collaboration with Cannon, which resulted in the use of gum-saline solutions to replace lost blood – a treatment calculated to have saved many thousands of lives. Bayliss was honoured with a knighthood in 1922, although he initially refused his investiture invitation because it clashed with a meeting of The Physiological Society.

Some Members remained in their Universities and labs, although many physiology classes were decimated. The future Nobel Laureate Charles Sherrington* (1857–1952, M 1885) stayed in Oxford working on the innovative student manual Mammalian Physiology: a Course of Practical Exercises (first published in 1919) which influenced generations of students over several decades. In the summer of 1915, Sherrington cycled to Birmingham and signed on for a short period as a munitions worker at the Vickers factory, working long shifts of over 75 hours a week. He proved a hard worker, his grateful foreman offering him a reference should he ever need one. Sherrington’s subsequent report on his working conditions to the War Office contributed to the creation of the Industrial Fatigue Board of which he was appointed Chairman.

Others remaining in Britain were the first appointees of the newly created Medical Research Committee (later Council, MRC), established in 1913 as a consequence of Lloyd George’s 1911 National Insurance Act. It was an inauspicious time for such a new venture. The key appointment of Scientific Secretary was accepted in early 1914 by the Cambridge physiologist who claimed his greatest contribution was introducing A V Hill to physiology, Walter Morley Fletcher. Reassured by Fletcher’s appointment that this unfamiliar new venture would be scientifically robust, Henry Dale* (1875–1968, M 1900) and George Barger* (1878–1939, M 1909) accepted research positions, and in July 1914 were dispatched to Germany to meet eminent physiologists and examine equipment prior to the establishment of their own labs. In Strasburg (then a German city) they were privately warned that mobilisation was imminent, and hastily and with some difficulty got back to the UK shortly before War was declared on 4 August. Dale, recently appointed a FRS for his work at the Wellcome Physiological Research Laboratories and who would later win the Nobel Prize for the elucidation of chemical neurotransmission, spent five years studying amoebic dysentery, gas gangrene, wound shock, antiseptics, and the production of British alternatives to the many drugs previously obtained from Germany.

The Physiological Society

As these brief, but varied, vignettes suggest Wartime contingencies and pressures pre-occupied many, if not all, Members of The Society. Efforts were made to maintain the regular programme of 7-8 meetings a year but this had dropped to five and all held in London by 1917. Concurrently, the number of Members able to attend and present Communications fell with Wartime duties and transport difficulties being cited in The Society’s Minutes. In 1915, the Secretaries reported that ‘notwithstanding the fact that so many members have been occupied in various matters in connection with the War, the standard of communications has been kept up’. The subject matter of some Communications did, however, give rise to concerns about published Proceedings being useful to the enemy. Immediately post-War, 10 meetings were held in 1919 and the Annual Report noted with satisfaction that the numbers of Communications ‘are rapidly increasing to their pre-War numbers’.

Membership decreased during the War years due to deaths, resignations and fewer new members. Importantly, however, a historic decision in 1915 allowed admission of the first six women Members. Ernest Starling had opposed the admission of women, arguing that the Society was primarily ‘a dining society and it would be improper to dine with ladies smelling of dog – the men smelling of dog that is’ (details in Tansey 1993, reprinted 2015), and he was closely involved in another Membership debate. At the Committee meeting of March 1916, attended by only five members, a letter was received from de Burgh Birch (1852–1937, M 1892), then Professor of Physiology at Leeds and commander of a Territorial medical corps in France, protesting at the inclusion of German and Austrian subjects in the Grey Book. The meeting unanimously decided to take no action, and there the matter seemed to rest until the 1918 AGM at which, according to Sharpey-Schafer’s History of The Physiological Society, ‘[i]t was moved and seconded’ that enemy nationals should be omitted from the membership list. Somewhat coyly, Sharpey –Schafer, usually a diligent and reliable scribe of the Society’s early archives, gives no further details of the proposers. The original Minutes record them to be Ernest Starling, seconded by Sir Henry Thompson, then Professor of Physiology in Queen’s University, Belfast. The AGM voted eight in favour and eight against the motion, leaving the chairman William Halliburton to cast his vote to maintain the status quo. However, German and Austrian members were discussed again at the Committee meeting in March 1920 when the question of their outstanding subscriptions was raised. The 1919 Grey Book lists three such members

(in addition to four Honorary Members), of whom two, the future Nobel laureate Otto Loewi* (1873–1961, HonM 1934) and Franz Müller, were alive. As neither could pay their arrears, the Committee Minutes of June 1920 record rather harshly, ‘[they] therefore cease to be members’.

Fractured international relationships between some individuals and organisations took time to repair. In March 1915, The Physiological Society had received a formal greeting from the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology sent to all combatant nations (the USA not then being in the War) with the ‘hope of an early and enduring peace, which will leave the nations with no permanent cause of rancor towards each other’. Sadly, some rancour and hostility did survive. As early as January 1919, Ernest Starling, his pre-War internationalism and use of German fully restored, reported proposals for an ‘Inter-Allied Congress’ by French physiologists. This was eventually held in Paris in 1920 but it was not until 1923 that the first fully ‘international‘ post-War Congress, with no restrictions on attendance, was held in Edinburgh as Fernando Cervero has recently analysed. A V Hill, in his Nobel prize banquet speech in 1923, acknowledged that ‘[t]he War tore asunder two parts of the world… Physiology, I am glad to know, was the first science to forget the hatreds and follies of the War and to revive a truly international Congress: my own country, I am happy to boast, was happy to be its meeting ground’.

References & Further Reading

Details of Society committee meetings,correspondence, AGMs and membership records are taken from The Society’s archives, housed in the Wellcome Library, London.

All named British physiologists, except de Burgh Birch and Sir Henry Thompson, have entries in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

* Indicates a Fellow or Foreign Member of the Royal Society, for whom an Obituary Notice or Biographical Memoir has been published by the Royal Society, accessible via https://royalsociety.org/journals/

Cervero, F (2017). Science and politics: The 1923 International Physiology Congress in Edinburgh. Physiology News 107, 33–35.

Henderson J (2005). A life of Ernest Starling. American Physiological Society, OUP.

Hill AV (1974). Memories and Reflections. [online] The Physiological Society.

Sharpey-Schafer E (1927). History of the Physiological Society during its First Fifty Years, 1876-1926. Part.1. J.Physiol 64 (Suppl), 1–76.

Sharpey-Schafer E (1927). History of the Physiological Society during its First Fifty Years, 1876-1926. Part 2. J Physiol 64 (Suppl), 77–181.

Tansey EM (1993). ‘To dine with ladies smelling of dog / A brief history of women and the Physiological Society’ in: Women Physiologists, ed L Bindman,AF Brading, EM Tansey. Portland press; reprinted in Wray S, Tansey T (2015). Women Physiologists: Centenary Celebrations and Beyond. London: Portland Press.

Van der Kloot W (2011). Mirrors and smoke: A. V. Hill, his Brigands, and the science of anti-aircraft gunnery in World War I. Notes & Records of the Royal Society 65, 393–410.

V der Kloot W (2014). Great Scientists Wage the Great War: the First War of Science. Fonthill, UK.