Physiology News Magazine

We need to talk about death

Collection of education-themed articles from Europhysiology 2022 conference

News and Views

We need to talk about death

Collection of education-themed articles from Europhysiology 2022 conference

News and Views

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.128.16

Katie Brown

Fourth-year medical student, University of Aberdeen, UK

There are few certainties in life – but one is that it will unequivocally end in death. Indiscriminate of gender, race, wealth or virtue, death is an inevitability certain to all. However, death is not merely an event. Death is a process – a process that has a universal outcome, at least in the physiological sense, but which is itself unique to every human life. However, the fundamental biological mechanisms underlying the process of death are almost entirely invariably consistent. Furthermore, these mechanisms may be simply explained by consideration of some central principles of physiology – a foundational bioscience subject in healthcare education – such as those proposed by Michael and McFarland (2020) to be the “core concepts of physiology”. Physiology teaching resources, such as textbooks, so often contain lengthy descriptions of conception, birth and development, but absolutely nothing about the natural events that occur at the other end of life. Moreover, whilst there is evidence to suggest that palliative and end-of-life care teaching has become more prevalent across healthcare curricula (Walker et al., 2016), the extent to which the process of death itself and the applicable underlying physiological mechanisms are explored in educational programmes is much more limited. If we as scientists and healthcare professionals are not willing to teach or discuss the subject of death, why would we expect students to understand what happens at the end of life?

Why is death omitted from the conversation?

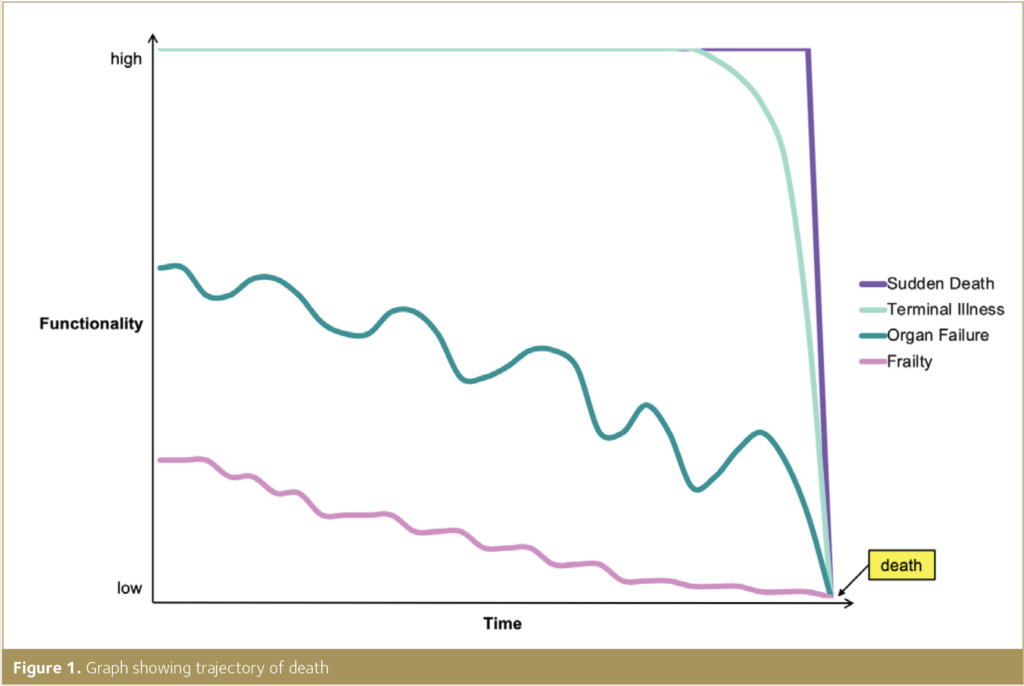

All physiology textbooks include detailed descriptions of the processes of cell death, such as apoptosis and necrosis. However, there is a significant scientific void in the exploration, discussion and understanding of the physiological basis of the changes that the human body goes through at the end of life. Those caring for patients – no matter of profession, position or speciality – ought to have, as an absolute minimum, a basic appreciation of the physiology of dying – just as knowledge of cardiovascular, respiratory and reproductive physiology is an expectation of those such individuals working in healthcare (The Physiological Society, 2020). Death can occur suddenly and unexpectedly or may be a more insidious and gradual process. Irrespective of the trajectory of death (Fig.1), if the dying process is not recognised due to a lack of such education, preparation to manage the dying patient, and those dear to them, cannot be expected to be even close to adequate. This can consequently cause or contribute to a state of high distress for all those aforementioned. It is therefore critical that the clinical observations indicative of the dying phase of life or imminent death, and crucially over and above this, the biological processes that cause these changes to arise, are made known to all healthcare professionals.

The death rattle and understanding the dying phases

The medical signs characteristic of the dying process include Cheyne–Stokes respiration and the so-called “death rattle” (Hui et al., 2014) – but these terms alone with no further description do very little to explain the changes that the dying human body is experiencing. Further noticeable alterations towards the end of life, as detailed by Minett and Ginesi (2020), include increased somnolence, mottling of the skin and reduced ability to maintain consciousness. The dying process, and the synonymous clinical observations (Fig.2), although unique to each and every individual, can be attributed to a much more finite range of physiological mechanisms, such as inadequate circulation or respiration, irreversible metabolic disturbance and loss of organ function. A grasp of these such biochemical and physical processes can shed light onto why apnoeic breathing, dysphagia and agitation occur at the end of life and, crucially, why death is happening. Such understanding can, in turn, facilitate the conversations with those close to the dying, which even the most experienced healthcare professionals can struggle to face at times. A clear, calm and honest explanation of what is happening to their loved one and what can be expected to be seen can, time and again, alleviate anxiety and distress – as described anecdotally by the prominent palliative care physician Dr Kathryn Mannix, in her critically acclaimed forthright memoir With the End in Mind: How to Live and Die Well (2018).

Buried six feet under – a problem for healthcare education

Discussion about death, in the educational, healthcare and day-to-day setting is necessary and relevant to all – now more so than ever. In January of this year, the Report of the Lancet Commission on the Value of Death was published, in which it was advocated that education about death “be integral, substantial and mandatory in the curriculum of every health and social care student” and continued throughout professional practice (Sallnow et al., 2022). Several healthcare curricula guidance publications or benchmark statements issue recommendations or requirements of the expected standards of physiology teaching and understanding. A comprehensive appreciation of physiological processes “across the lifespan” (College of Operating Department Practitioners, 2018; College of Paramedics, 2019) is often stipulated. Some resources further clarify the accepted constitutive phases of the continuum of life, including the publication by The Physiological Society, Physiological Objectives for Medical Students (2020), identifying “foetal, neonatal, childhood, adolescence and adulthood” as the distinctive stages of human life. However, none of the documents examined considered death as such a part of life, nor specified a necessity for an understanding of the biological mechanisms underlying dying and death. Surely this is a glaring omission in the education and practice of our healthcare science and professionals of the moment and of the future who care for our dying, dead and bereaved? The discussion has to start somewhere – but without reconsideration of the content of current healthcare and physiology education programmes and attitudes towards the delivery of teaching about death, this subject matter will continue to be buried six feet under. We simply cannot afford to allow this to happen – we need to talk about death.

References

College of Operating Department Practitioners (2018). Bachelor of Science (Hons) in Operating Department Practice Curriculum Document. Available online at: https://www.unison.org.uk/at-work/health-care/representing-you/unison-partnerships/codp/education-and-standards/ [Accessed 12 Feb 2022].

College of Paramedics (2019). Paramedic Curriculum Guidance. Available online at: https://collegeofparamedics.co.uk/COP/ProfessionalDevelopment/Paramedic_Curriculum_Guidance.aspx [Accessed 12 Feb 2022].

Hui D et al. (2014). Clinical signs of impending death in cancer patients. Oncologist 19 (6), 681-687. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0457

Mannix K. (2018). With the End in Mind: How to Live and Die Well. 1st Ed. London: HarperCollins Publishers.

Michael J, McFarland J. (2020). Another look at the core concepts of physiology: revisions and resources. Adv Physiol Educ. 44(4), 752-762. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00114.2020

Minett P, Ginesi L. (2020). Anatomy & Physiology: An Introduction for Nursing and Healthcare. 1st Ed. Banbury: Lantern Publishing Ltd.

Sallnow L et al. (2022) Report of the Lancet Commission on the Value of Death: bringing death back into life. Lancet 399 (10327), 837-884. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02314-X

The Physiological Society (2020). Physiological Objectives for Medical Students. Available online at: https://www.physoc.org/policy/higher-education/supporting-medical-education/ [Accessed 09 Feb 2022].

Walker S et al. (2016). Progress and divergence in palliative care education for medical students: A comparative survey of UK course structure, content, delivery, contact with patients and assessment of learning. Palliative Medicine 30(9), 834-842. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216315627125