Physiology News Magazine

What’s new in anaesthesia?

Bill Winlow describes some of the safety aspects of anaesthesia, including a new compound that reverses neuromuscular blockage, closed loop feedback systems for monitoring anaesthesia and current ideas on brain protection in neurosurgery

Features

What’s new in anaesthesia?

Bill Winlow describes some of the safety aspects of anaesthesia, including a new compound that reverses neuromuscular blockage, closed loop feedback systems for monitoring anaesthesia and current ideas on brain protection in neurosurgery

Features

Bill Winlow

Prime Medica Ltd, Knutsford, Cheshire

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.54.11

In my new role as a medical writer, I edit a newsletter entitled aspects in anesthesia on behalf of Organon Inc, and this entails a good deal of travel to report on meetings. Between 31 May and 3 June I attended Euroanaesthesia 2003 In Glasgow. This was an historic joint meeting of four European societies and was hosted by the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. There was a very comprehensive programme of refresher courses, together with presentations and discussions of the latest research, primarily in Europe. Later in the year, 11-15 October, I went on to the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) annual meeting in San Francisco. This was an enormous meeting with over 17,000 participants. There were review lectures and refresher courses to suit all tastes as well as a wide range of posters and a very large trade display. Here are a few of the presentations from these conferences that interested me, particularly in terms of patient safety.

Postoperative residual curarization – a continuing problem

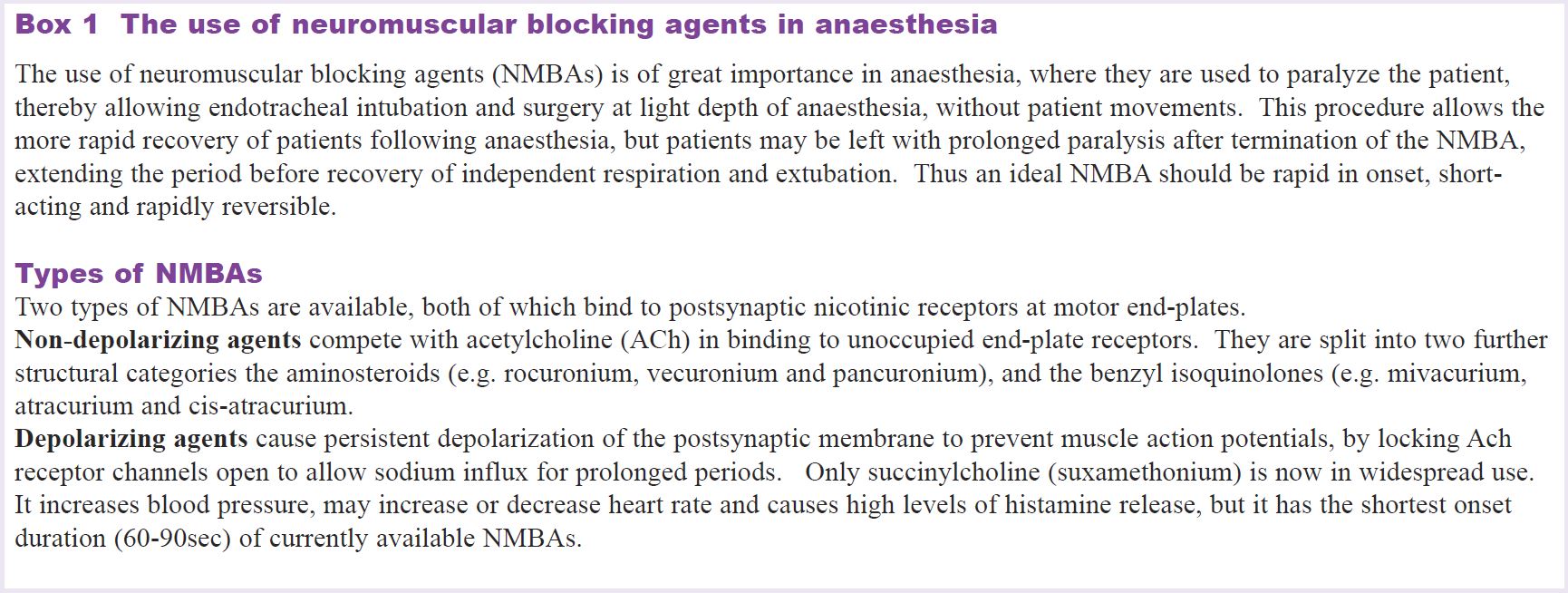

For general anaesthesia three main groups of drugs are given: hypnotics to induce unconsciousness, analgesics to reduce pain during and after surgery and muscle relaxants to produce complete muscle paralysis during surgery. Neuromuscular blocking agents (NMBAs) are therefore, an essential adjunct to patient care during anaesthesia (see box 1).

Jørgen Viby-Mogensen, Denmark, presented data showing that myths about postoperative residual curarization (PORC) – such as it has no clinical significance or that it can easily be avoided by using clinical tests, or an intermediate-acting muscle relaxant for intubation, etc. – are not true. Although there are numerous relatively reliable tests to detect PORC, such as 5 sec sustained head lift, leg lift, hand grip, etc. he said that these alone would not always identify it. Furthermore, it would appear that such tests are not used routinely. According to a recent Danish survey of 251 anaesthetists, >50% could not distinguish between reliable and unreliable tests and <50%used reliable tests on a daily basis. In addition, 75% did not know that clinically significant PORC could not be excluded by tactile or visual evaluation of response to nerve stimulation. There is no suggestion that anaethetists elsewhere are any better at distinguishing PORC than their Danish counterparts!

Professor Viby-Mogensen presented data showing that clinically significant PORC occurred in 25–50% of procedures lasting <90 min (using intermediate-acting muscle relaxants) and in 25–50% of procedures lasting >90 min (using long-acting muscle relaxants). Finally, he showed that PORC could significantly reduce patients’ response to hypoxia, reduce oesophageal sphincter tone and increase episodes of aspiration, thereby increasing the possibility of postoperative pulmonary complications. He concluded that failure to monitor neuromuscular response objectively after using muscle relaxants represents substandard care.

A binding agent that reverses neuromuscular blockage

Given the problems outlined by Jørgen Viby-Mogensen, I was very interested to hear about the talk by Bertrand Debaene, France, on new muscle relaxants in development. I was also interested in the poster by Bom et al. at the ASA meeting (Rapid reversal of rocuronium-induced neuromuscular block by Org 25969 is independent of renal perfusion. ASA Meeting Abstracts, A-1158), as well as his presentation on the same subject at the recent joint meeting of Phys Soc and Pharm Soc in Manchester.

Muscle relaxants should ideally have both a rapid onset and a rapid offset, particularly with respect to intubation, but Debaene showed that some patients still have residual paralysis 120 min after a single intubating dose of an intermediate muscle relaxant. Thus, monitoring (e.g. acceleromyography) is required to ensure that the TOF (train-of-four) ratio is >0.9 before the patient is transferred to the recovery room (see box 2). Alternatively, a reversal agent (such as neostigmine) is given. However, neostigmine has little effect against profound block and can stimulate muscarinic and nicotinic receptors in other tissues. This is because neostigmine does not reverse muscle blockade, but acts as a competitive anticholinesterase, which effectively increases the agonist concentration to overcome the neuromuscular blockade.

A new concept is to chemically sequester the neuromuscular blocking agent. In the case of the muscle relaxant rocuronium, this can be achieved with a tubular cyclodextrin (Org 25969), which encapsulates rocuronium, rather like a glove over a hand. Studies in healthy volunteers have shown that it is capable of reversing profound rocuronium blockade within 2–3 min. However, unlike neostigmine, it has no muscarinic or nicotinic effects. What is more the combined compound appears to pass safely through the kidneys into the urine. If this drug successfully gets through all phases of clinical research trials, it would be a great step forward in solving the problem of PORC, thereby increasing patient safety.

Closed loop anaesthesia

As a physiologist, I am interested in feedback systems, and the idea of closed loop anaesthesia sounded fascinating. In closed loop control of anaesthesia, a computer program maintains the targeted effect (i.e. the set point defined by the anaesthetist) by adapting the amount of the different drugs administered. The anaesthetist only takes over if a major problem occurs. The rationale is that computers are superior to humans in terms of sustained attention, vigilance and prolonged decision making.

However, according to Michel Struys (Belgium), controller reliability strongly depends on the reliability of the physiological signal being measured. Unfortunately, depth of anaesthesia is difficult to measure and surrogate measures, such as blood pressure or muscle activity, may be used as the controlled variable, but these have not proved totally reliable. Investigators have previously found disadvantages when using univariate indicators derived from the electroencephalogram (EEG). More recently, multivariate statistics have been used to combine various features of the EEG into a single index, the bispectral index (BIS©).

Professor Struys said that BIS correlates well with changes in the level of hypnosis produced by anaesthetics and sedatives and, compared with other monitoring systems, should result in less drug usage, lower costs and faster return to consciousness for patients. The major challenge now is to establish the safety, efficacy, reliability and use of closed loop anaesthesia under extreme clinical conditions.

The good, the bad and the maybe

In his presentation James E Cottrell (SUNY, New York) considered the use of a number of drugs and techniques that may or may not act as brain protectants in neurosurgery.

The good Although it is not a powerful neuroprotectant, remacemide, a glutamate antagonist through N-methyl D aspartate (NMDA) channel blockade, was effective in retaining patients’ ability to learn after coronary artery bypass surgery, as evidenced by neuropsychological tests. Professor Cottrell then pointed out that sodium influx is the first step in the ischaemic cascade and that truncating the initial steps of the cascade reduces the damage done by downstream events. Lidocaine, which has demonstrated neuroprotective properties, both in vivo and in vitro, blocks sodium influx and may reduce post-ischaemic injury by blocking apoptotic cell death via cytochrome C release and caspase-3 activation.

Another approach to neuroprotection is to pre-condition the brain with pre-operative hyperbaric oxygen or erythropoietin (EPO). According to Professor Cottrell the most impressive trial of a known pre-conditioning agent used erythropoietin, which is endogenously produced in the brain after hypoxic or ischaemic insults. Under normal circumstances, EPO increases the production of erythrocytes by preventing their apoptotic self destruction during differentiation. In the brain EPO is produced primarily by astrocytes in the ischaemic penumbra, where there is also an up-regulation of EPO receptors. According to Professor Cottrell EPO stimulates ‘proteins of repair, diminishes neuronal excitotoxicity, reduces inflammation, inhibits neuronal apoptosis and stimulates both neurogenesis and angiogenesis subsequent to experimental ischaemic, hypoxic and toxic injury’. EPO also improved neurological outcomes and mental function. Professor Cottrell suggested that, assuming it gets through all its clinical trial development, EPO may eventually prove to be a very good prophylactic, pre-conditioning neuroprotectant, if administered 24–48 h before surgery.

The bad Professor Cottrell discussed a number of anaesthetic and adjuvant drugs, currently in use, but which have had disappointing effects as neuroprotectants. These included nitrous oxide, ketamine, nimodipine and tirilazid. Based on a wide variety of studies, none of these agents were felt to exert significant neuroprotective effects. At a technical level he also indicated that post-operative mild hypothermia was not advantageous in head injury patients and might only delay neuronal death subsequent to an ischemic event.

The maybe Professor Cottrell reviewed a number of promising techniques and drugs. Low normothermia (36oC) may be used in both the neuro and cardiac ICU to protect non-ventilated patients against infection and subsequent fever, which is strongly associated with a poor outcome. There is also accumulating evidence that prophylactic mild hypothermia offers a neuroprotective effect, since early cooling may have the potential to reduce ischaemic injury that is still developing.

Magnesium blocks both ligand and voltage dependant calcium entry into cells, but laboratory evidence indicates that pre-ischaemic magnesium administration is much more protective than post-ischaemic administration, which would probably limit its usefulness. However, a prospective, randomized trial of prophylactic magnesium in cardiac surgery patients is currently in progress.

Finally, Professor Cottrell stated that the inert gas xenon, an NMDA receptor antagonist, has shown some neuroprotective effects in animal studies, including improved neurocognition.

No patient shall be harmed by anaesthesia

A cynic might say that we are still no closer to understanding how anaesthetics really work than we were 50 years ago, but anaesthesia safety has improved markedly over recent decades and has become institutionalized, according to Jeffrey Cooper (USA). The main contributions to anaesthetic safety have been leadership, research on error, safety prioritization, better technology, drug safety, and a safety culture. Institutionalization of anaesthetic safety has evolved through national safety committees, anaesthetic patient safety foundations, studies of closed claims, establishment of standards and protocols, etc. Dr Cooper said that challenges remain as patients are now older and sicker, procedures are more challenging, and there is pressure for anaesthetists to work faster and surgeons to be more productive.

To meet the new pressures and to maintain and continue safety improvements, Dr Cooper stressed the need to compare anaesthetic safety measures with those of high-risk organizations (HROs), which are intrinsically risky, but which have low failure rates, e.g. the flight deck of an aircraft carrier. The key principles to adopt from HROs include: a top-down commitment to safety; optimized structures and procedures; intensive training (operations and simulations); maintaining an active safety culture; learning from accidents and incidents; and teamwork by anaesthesiologists, surgeons and nurses. In summary, ensuring safety is a never-ending process, but the goal must be that no patient shall be harmed by anaesthesia.

Postscript

In conclusion, we still don’t really know how anaesthetics work, but patient safety is a primary concern and new drugs and techniques to aid more rapid recovery are probably of great interest to all concerned. From my point of view the amount of applied physiology and pharmacology makes reporting on anaesthesia profoundly interesting in its own right. A detailed report of the ASA conference can be found in aspects in anesthesia online (http://www.organon-conferences.com/ASA2003).