Physiology News Magazine

Why does Impact Factor still have impact?

News and Views

Why does Impact Factor still have impact?

News and Views

David Miller

Glasgow University, UK

https://doi.org/10.36866/pn.93.12

Surely not another rant against the Journal Impact Factor (ImpF)? We all know ImpF is no way to represent anything much of interest or relevance about either the journals we publish in, or the publishing scientists themselves, right?

But wrong, apparently, so far as one hears and reads almost daily. The imminence of REF (the Research Excellence Framework) – the latest exercise designed to assess and define government funding of research universities in the UK – brings this thorny issue back out yet again (see e.g. Richard Naftalin’s article, 2013). Beyond REF, it cannot be overlooked that ImpF has (allegedly) been deployed for many years by grant-giving bodies and by university appointment and promotion committees too. So, here we go again…

Informed rubbishing of ImpF has a long history (see e.g. Colquhoun (2003); Molinie & Bodenhausen (2010); Seglen (1997); Wouters (2013)). But despite the erudition and overwhelming technical evidence of its invalidity, league tables based on ImpF haven’t been killed off, yet. An impressive plea to abandon ImpF in any academic context was made earlier this year: the San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA, 2013). Signatories include AAAS, Wellcome Trust, EMBO, PNAS, PLOS and our Society’s journals, but importantly in the context of REF, also by the UK’s Higher Education Funding Councils. Despite DORA’s powerful plea and its supporting case, the Research Deans in British universities have not abruptly altered their practices, allegedly.

For this article, I had hoped to be able to quote chapter-and-verse about REF submission criteria, at least for the Russell Group universities. However, for fear of institutional retribution and career suicide, nobody was willing go on the record about their own employer. Thus, all I can do is to report what others have told me ‘in confidence’. It is quite clear that Research Deans – or whoever is leading the task of deciding whose papers, and which papers, are in or out of REF – are ruthlessly using ImpF in their deliberations about physiologists. However the techniques are being dressed up for public consumption, it is obvious that the laudable guidance and explicit instructions about quality assessment processes given in the REF documents (see e.g. REF, 2011) is being ignored. The practice is clearly widespread and, given the published guidelines (‘No sub-panel will make any use of journal impact factors, rankings, lists or the perceived standing of publishers in assessing the quality of research outputs.’ REF, 2014), surprisingly explicit, or so I am assured ‘off the record’ by respondents from several Russell Group institutions.

The sharp edge for physiology, of course, is that de facto, an ImpF of 5 is being seen as the lower boundary for submission of papers (in basic medical sciences where most physiologists will be returned). This arbitrary cut-off is in large part fuelled by the relatively high ImpFs ‘enjoyed’ by many clinical journals. (More on this detail later.) It is thus a matter of considerable professional anguish that The Journal of Physiology, indubitably a leading international journal in our discipline, had an ImpF of 4.380 for 2012. (Perversely, so many significant figures are reported for an ‘index’ lacking significance!) It is clear (e.g. from David Paterson’s report to the Society’s AGM in July at IUPS 2013 in Birmingham) that, although The Journal of Physiology editors are signatories to DORA, they still feel constrained by Realpolitik to do everything they can to ‘enhance’ this potentially devastating ‘metric’. Even the Society’s website reports the ImpF of J Physiol and Exp Physiol prominently.

ImpF, as you will be aware, only looks at the total number of citations gained by a given journal over the two calendar years immediately before the census date (explaining why I have long preferred the term ‘Ephemerality Index’ for ImpF). It is interesting to note that Eugene Garfield (1998) – who had himself devised ImpF in 1963 with I. H. Sher – noted the large relative enhancement of 7-year and 15-year citation indices for ‘long impact’ journals like J Physiol when compared with ranking by their ‘standard’ 2-year ImpF. These critical caveats – and many more – are wilfully neglected by those still in the thrall of ImpF.

The reader might need a refresher course in ImpF ‘bibliometrics’. David Colquhoun (2003) succinctly provided the principal criticisms of ImpF per se:

(a) ‘high-impact journals get most of their citations from a few articles’

(b) [ImpF deploys] ‘the unsound statistical practice of characterizing a distribution by its mean only, with no indication of its shape or even its spread’.

In support of these points, Colquhoun exemplified for (a) that Nature (in 1999) achieved half its total citations from just 16% of its articles and for (b) that 69% of a random sample of 500 biomedical papers over a 5-year count period had fewer than the mean citation score (of 114) whereas one paper had been cited at more than 20 times that mean. Nature itself (2005) quotes similar examples from 2002–3 against, as-it-were, its own enviable ImpF.

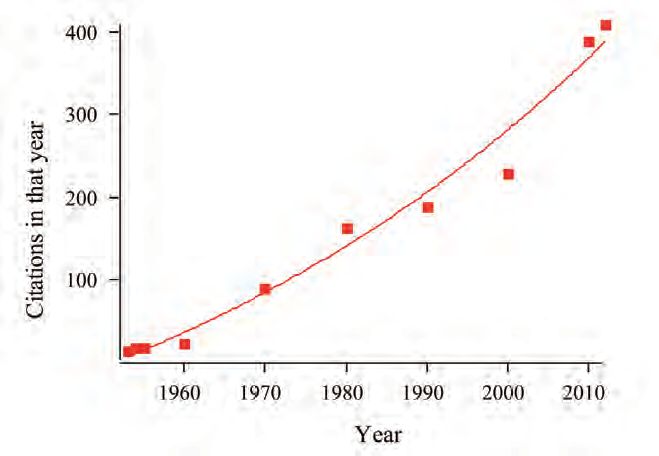

Now let us take a closer look at examples with immediate relevance to physiology. The Journal of Physiology captured a total of 46,000 citations in the last ImpF 2-year window. Of these, nearly 800 were for a single paper, one published in 1952. Yes, it’s Hodgkin and Huxley (vol. 117, pp. 500–544). The annual citations of this seminal work have been rising almost linearly since 1952 (Fig. 1).

Nothing about ImpF can capture the real impact of a paper of this kind, rare though it is, not even its citation impact. Equally, ImpF fails to capture the ‘average’ J Physiol papers either. These tend to accumulate citations over several years, generally after a ‘slow’ start (in ImpF terms). The half-life for

J Physiol papers (the time taken to accumulate half their eventual total citations) is longer than 10 years. Many might argue that this is real impact.

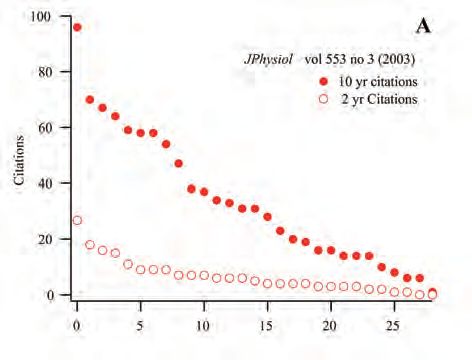

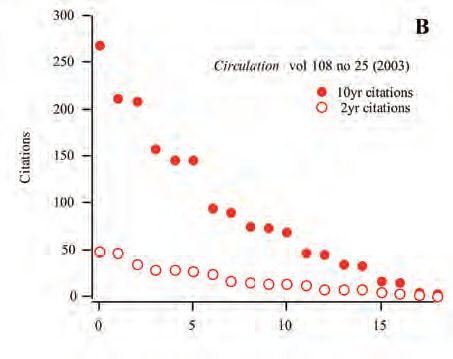

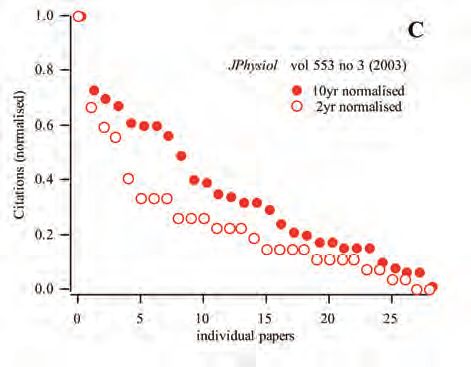

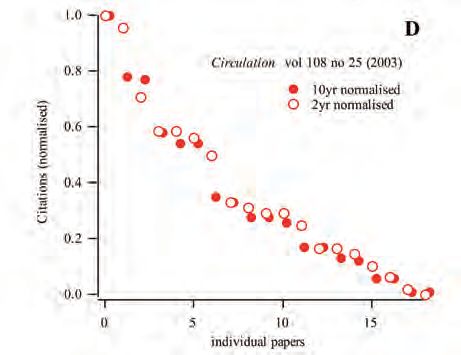

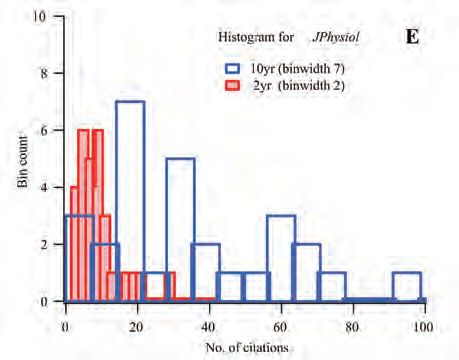

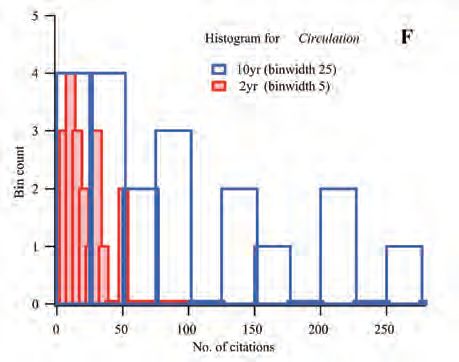

To illustrate these points, I have taken at random one issue of J Physiol (vol. 553, issue 3, the last in 2003). I have compared its ImpF-relevant data with that from the last 2003 issue for Circulation, a physiology-relevant journal, but one that has a much higher ImpF (largely by dint of citations by its huge clinical-academic readership). For medicine-dominated REF submissions which will generally include physiologists, the comparison is salutary; in ImpF terms, Circulation is ‘in’, but J Physiol is ‘out’. Figure 2A and B shows the raw citation data after 2 years (i.e. the numbers contributing to ImpF for 2006) and after (nearly) 10 years for both journals. The data points represent the individual citation totals (ordinate) of each of the 28 J Physiol papers (Fig. 2A, abscissa) and 18 Circulation papers (Fig. 2B) in the respective December 2003 issues. Each curve shows, as with almost every journal, that just a few papers are heavily cited, but that most are cited very much less. The general shape of the citation profiles looks broadly similar at 2 and 10 years for each journal, albeit on different scales. But to facilitate comparison, the data are then replotted with each normalised to the maximum citation numbers for 2 or 10 years (Fig. 2C and D). The shape of the normalised profiles for Circulation (Fig. 2D) is now seen to be little different between 2 and 10 years of accumulated citations. However, for J Physiol, the shapes are clearly different. After 10 years, several papers have disproportionately gained citations relative to the best-cited one. We can even calculate a ‘normalised ImpF’, the average citation rate of all papers expressed relative to the most-cited one. This ‘normalised ImpF’ after 10 years is almost unchanged from the 2-year rate for Circulation (0.34 vs. 0.37 of the maximum, respectively), whereas for J Physiol it is some 40% higher (0.35 vs. 0.25). These profiles are for just one, randomly chosen issue of each journal. They show why ImpF fails, even on its own crude terms, to provide a satisfactory ‘metric’ of the impact of papers in J Physiol whereas for Circulation it is at least more consistent over time. (Some highly rated journals such as Nature, Cell and Neuron and many clinical journals show falling ‘impact factors’ for citation periods of longer than 2 or 3 years; examples of ‘brief impact’, perhaps?) Finally, the histograms of the data from panels A and B are shown (Fig. 2E and F). These skewed plots further confirm why a crude average 2-year citation rate (i.e. ImpF) is inadmissible as a description of citation pattern, confirming Colquhoun’s points (a) and (b) above. (For readers interested in a recent analysis of statistical, and other, anomalies inherent in ImpF, see Vanclay (2013). The author shows (his Table 5) the huge discrepancy of mean (=ImpF), median and modal citation rates for a range of journals, amongst many other damning details.)

Figure 2

In the numerate sciences, an attempt to deploy a ‘metric’ like ImpF within an article would be rejected by the referees out of hand (“Methods Section: The skewed, non-normal distribution of our statistic will be represented by its arithmetic mean.”). Meanwhile, the same journals are virtually forced to agonise about their own set of Emperor’s Clothes in the crazy fashion-world of ImpF. Worse, senior scientists and academic clinicians who, as referees, would decry this spurious ‘metric’ do use it – allegedly – in making decisions about staff hire-and-fire, research quality assessment, funding and research strategy. Bosses might publicly claim (as they must) that their assessment of publication quality is ImpFindependent, yet a cursory glance at the ‘approved journals’ lists at every UK Research Dean’s elbow – allegedly – reveals congruence with ImpF ‘data’.

Publishers could claim, with some justification, that ImpF is part of their ‘real world’, even though they profess to hate it. If that is true, then it is we academics who are to blame for having ever given it any credence. It really is up to the academic community to acknowledge the stark nakedness of the Emperor ImpF as any sort of a ‘metric’. The ‘justification’ that ImpF is ‘rough and ready’ or ‘the best we have’ is grotesque. Perhaps our infatuation with ImpF is like that for Schools League Tables, the Sunday Times ‘Best Universities’ tables and all the rest; we just can’t resist taking a peek.

Finally, there is growing interest in author-specific citation ratings, typified by the ‘H-factor’ (Hirsch, 2005; Bishop, 2013). But even this approach must be treated with great caution, as the online debate of a recent Nature article by Macilwain (2013) clarifies: here Paul Soloway remarked: “In the 10 years since [the] 1950 PNAS paper was published in which Barbara McClintock described the seminal work that earned her Nobel Prize [1983 for Physiology or Medicine], the paper was cited only 30 times and received a minimal amount of attention [Fedoroff, PNAS 109: 20200-3 (2012)]. I can only imagine how McClintock would have been judged if the H-factor counters been born and subjected her to their scrutiny. There is no metric for creativity.”

References

Bishop D (2013). Impact factors, research assessment and an alternative to REF 2014 (blog reposted at http://blogs. lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2013/02/08/impact- factors-and-an-alternative-to-ref-2014/).

Colquhoun D (2003). Challenging the tyranny of impact factors. Nature 423, 479.

DORA (2013). see http://am.ascb.org/dora/

Garfield E (1998). Long-term vs short-term impact: does it matter? Physiologist 41, 113–115.

Hirsch JE (2005). An index to quantify an individual’s scientific research output. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102, 16569–16572.

Lawrence PA (2003). The politics of publication. Nature 422, 259–261.

Macilwain, C (2013). Halt the avalanche of performance metrics. Nature 500, 255 and online discussion at: http://www.nature.com/news/halt-the-avalanche-of-performance-metrics-1.13553.

Molinie, A & Bodenhausen, G (2010) Bibliometrics as Weapons of Mass Citation. Chimia, 64, 78-89

Naftalin R (2013). http://www.the-scientist.com/?articles.view/articleNo/36291/title/Opinion–Rethinking-Scientific-Evaluation/Nature Editorial (2005). Not so deep impact. Nature 435, 1003–1004.

REF (2011). Documentation at http://www.ref.ac.uk/pubs/2011-02/

REF (2014). Documentation on ‘Research Outputs (REF2)’ at http://www.ref.ac.uk/faq/researchoutputsref2/

Seglen PO (1997). Why the impact factor of journals should not be used for evaluating research. BMJ 314, 498–502

Simons K (2008). The misused impact factor. Science 322, 165.

Vanclay JK (2012). Impact Factor: outdated artefact or stepping-stone to journal certification? Scientometrics DOI 10.1007/s11192-011-0561-0 (at http://arxiv.org/pdf/1201.3076v1.pdf) .

Wouters P (2013). http://citationculture.wordpress.com/category/citation-analysis/journal-impact-factor/